Introduction

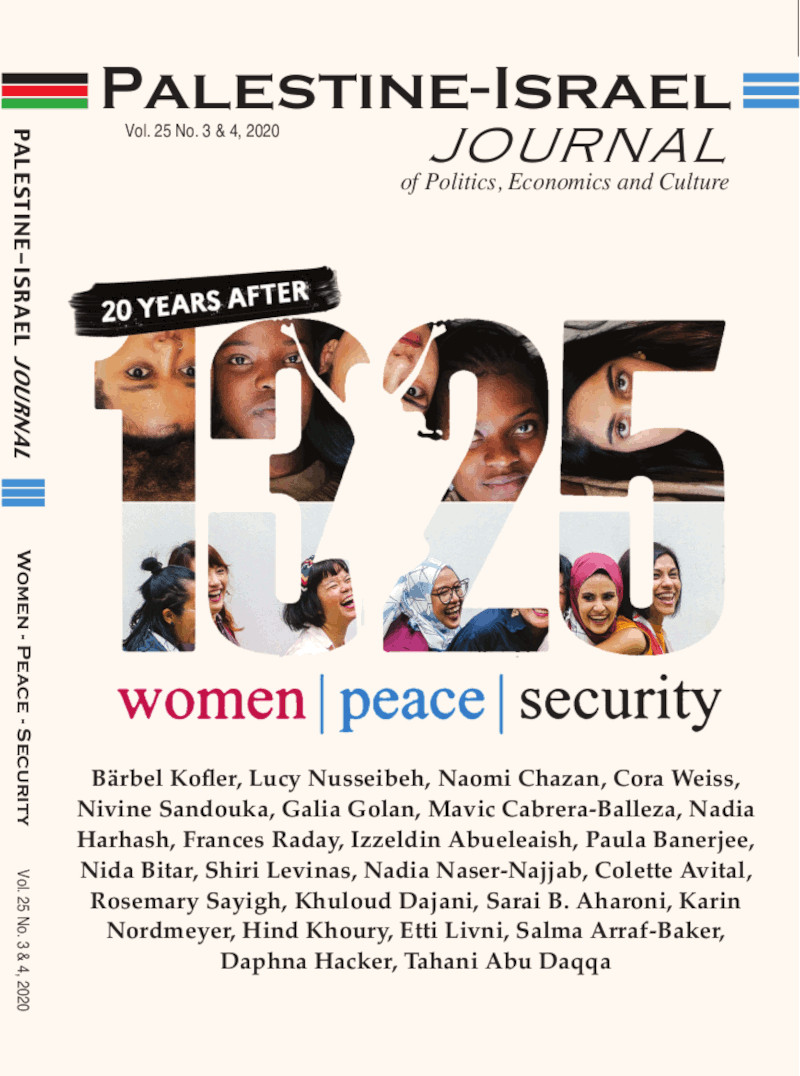

The United Nations Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1325 on October 31, 2000. This resolution, which focuses on women, peace, and security, calls on member states to “protect women and girls from gender-based violence … in situations of armed conflict;” “adopt a gender perspective” when “negotiating and implementing peace agreements;” increase women’s participation at decision-making levels in conflict resolution and peace processes;” and increase women’s representation “at all decision-making levels in national, regional, and international institutions and mechanisms for the prevention, management, and resolution of conflict.” In this article, I consider how these different imperatives have been addressed in the Palestinian-Israeli context. In particular, I will focus on the 1967 territories and on the response of the Palestinian Authority (PA) to the resolution.

The issues of women’s representation and participation can be sufficiently considered only within a wider context. The reverse also applies, however; issues of democracy and development are insufficient addressed if they lack a gender dimension or analysis. As a case in point, consider Sadik Jalal al-Azm’s Self-Criticism After the Defeat (1967), which emphasises the importance of democracy, gender equality, political parties, and social institutions for Arab progress (Al-Azm, location No. 746)i. In discussing how the challenges of colonialism can be addressed, he links the liberation of society to the liberation of women: “The greatest example of entirely wasted Arab human resources is the completely and utterly excluded half of the Arab people, and I mean by this Arab women” (ibid, location No. 2274).

Women’s participation in the first intifada perfectly encapsulates this link between women’s liberation and the anti-colonial struggle. During this event, women’s participation was promoted through political parties represented in trade unions and other social institutions. Palestinian women, therefore, sought to gain equality in the independent state they fought for. I recall that in our engagements with international women’s solidarity groups, we did not question that women’s rights would follow national liberation, as if through a natural process. We confidently explained that Palestinians had learned the lesson of other post-colonial Arab countries that lacked democracy and gender equality.

This illusion was quickly shattered when the newly established PA applied Jordanian law in the West Bank, including the requirement that a woman should first receive her husband’s consent before obtaining a passport. In 1994, women’s rights activists campaigned against the law. A letter was sent to President Yasser Arafat; media campaigns were launched; and female and male demonstrators mobilized. In one meeting, activists asked the deputy prime minister: “Why didn’t you ask us to get the consent of our male guardians when our political leadership wanted us to carry messages from one country to another?” Two years later, he issued a decree that women age 18 and over did not require a guardian’s consent to obtain a passport.ii

The Post-Oslo Period

Before Oslo I was signed in 1993, women from various NGOs established the 'Women’s Affairs Technical Committee' (WATC) in 1992, with the aim of defending and supporting equal rights.iii When the PA was established, women’s groups, organizations, and activists campaigned for equal citizenship. In 1994, Birzeit University established a 'Women’s Studies' program that would work with Palestinian civil society. Women worked on separation issues related to gender equality and national rights, including the codification of Palestinian personal status law. Any evaluation of their “success” would of course need to acknowledge the wider context and take it into account. Azzouni observes:

Nonetheless, all discussions about Palestine’s constitution, its laws and their impact on women must also address the limitations

imposed by the Israeli occupation, which heavily influences the ways in which the PA conducts its affairs, how Palestinians conduct

their daily lives and the personal security of all Palestinians.iv

Of these challenges, fragmentation, which became increasingly pronounced after Oslo II, presented the greatest challenge to gender equality and constitutional rule. In interacting and interfacing with political division and colonial activities, it hindered the reform and enforcement of law.

PA dependence — in particular financial dependence — was a structural feature of the accords that further enhanced Israel’s control of the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT). The practice of security coordination created a divide between elites and the general public and also weakened political parties. This created a democratic deficit that was specific to the Oslo period in many respects, as the political parties had previously been responsive to popular needs, most noticeably in the area of service provision. They were "close" to the public both in the methods they applied and the focus of their work. The political parties enabled women to take leadership roles and directly contribute to decision-making. This changed in the Oslo era. Rima Hammami observes:

[T]his period [was] marked by contradictions within the organizations between their contending aims (grassroots development versus

political mobilisation), within their leadership structures (party hierarchy versus professional staff versus community participation), and

over their funding base (political versus donor money versus community support) (1995:55)v

Here she focuses on the internal configuration of Palestinian political parties. The external context, however, and specifically its impact on women’s participation was equally important. Education is an instructive example in this respect, as the division of land, the construction of the separation barrier, and the imposition of closures and roadblocks have contributed to a school dropout rate that is particularly high among young girls and women.vi Palestinian women have responded to this situation with activism focused on gender equality and legal reforms. I will now refer to the second intifada to explain how Palestinian women excluded from decision-making were able to initiate political campaigns for national rights.

The Second Intifada and Political Deadlock

The accords postponed several crucial issues, including Israeli settlements, Jerusalem, and Palestinian refugees, to “final status” negotiations. In 1999, polling confirmed that Palestinians were still optimistic about the peace process despite repeated closures and continued hardship.vii The second intifada was an uprising that broke out several months after the collapse of the Camp David negotiations. In direct contrast to its predecessor, it was highly militarized, which limited women’s opportunities for broad-based participation.

In the previous intifada, women had made a vital contribution, which included working with Israeli women’s groups and activists. This continued, albeit to a lesser extent, into the post-2000 period. The People-to-People Program (P2P), which emerged from Oslo II and was envisaged as the “grassroots” component of the peace process, was particularly problematic for these observers. Despite its apolitical framing of “participation,” Palestinians widely viewed it as a form of normalization.viii After registering a rising tide of Palestinian discontent about the program, the General Assembly of the Palestinian NGO Network (PNGO) eventually issued a press release that called for all related activities to be suspended. It also insisted that any contact with Israeli NGOs should be conditional on the recognition of Palestinian national rights, including the right of return.ix

Significantly, Bat Shalom, a feminist organisation, was one of the few Israeli NGOs to respond to the press release. On March 25, 2001, it published a letter in Al-Quds newspaper that was addressed to the Palestinian people. It stated:

- We believe that Israel’s recognition of its responsibility in the creation of the Palestinian refugees in 1948 is a prerequisite to finding a just and lasting resolution of the refugee problem in accordance with relevant UN resolutions;

- We pledge to do our utmost to influence the Israeli government to dismantle the apparatus of occupation and oppression;

- We Israeli women, Jewish and Palestinian, in the name of all progressive Israelis, join hands in solidarity with those Palestinians and Palestinian organizations in the Occupied Territory who continue to struggle for our common vision of peace, coexistence and cooperation in the Middle East.x

The ability of Palestinian women to respond was, in this and other instances, likely to be restricted to cooperation in the NGO field. In addition to the sensitivities that surround engagement with Israelis and Israeli organizations, Palestinian women also have a limited role in decision-making and political processes. These deficiencies manifest across various levels and dimensions of political participation, and this again underlines why it is so important to initiate legal reforms that will give women full equal rights of political participation.

Challenges That Confront Palestinian Women

At this time, when Palestinians are confronting annexation plans and the pandemic, violence against women is increasing. The state of continued colonial control, economic crisis, fragmentation, lawlessness, and ongoing division is negatively impacting women and their advocacy and lobbying efforts. Palestinian police cannot reach areas under Israeli control, such as Area C, to protect women.xi Civil society organizations and women’s NGOs have sought to address gender-related disadvantages and violence against women with a degree of success,xii but this important work requires complementary interventions focused on gender-related discrimination, exclusion, and marginalization in the OPT. The PA lacks the resources and infrastructure to provide effective women-focused services, and Palestinian society also remains deeply patriarchal.xiii

It is clearly insufficient to theorize this as an issue of service provision or a social problem, however, as both can be understood only in a wider political context of colonization. It is essential to incorporate a gender dimension into the analysis of colonial practices. For example, one recent study considers how Israel’s checkpoints, land confiscation, land fragmentation, and separation barrier have negatively impacted women’s land ownership.xiv Meanwhile, the implications of the pandemic and lockdowns must also be viewed within the context of Israeli restrictions on movement and violations of human rights. Services and support are inevitably impacted as a result. Therefore, CARE Palestine has urged Israeli authorities to ease restrictions on movement for essential medical staff and to contribute to the establishment of appropriate public health and safety arrangements. It has also requested the facilitation of the work of humanitarian agencies that provide essential humanitarian services (including education, food, health, protection, sanitation, shelter, and water) in a manner consistent with International Humanitarian Law (IHL).xv

Conclusion

UNSC Resolution 1325 is a positive step toward ensuring that women are protected against violence and abuse. It emphasizes the political participation of women and their representation in decision-making and also establishes that they should have a voice on issues related to national and civil rights, but Palestinian human rights are consistently and routinely violated by Israeli measures that affect all aspects of their lives. The resolution’s call on states to “protect women and girls from gender-based violence” is not applied in the OPT, where the Israeli state is directly responsible for this violence, although the international community, whether through its direct complicity or tacit tolerance, is clearly implicated in these abuses.

The PA is not in a position to challenge or change this, as it is currently preoccupied with its own survival.xvi In any case, it was not established to address the consequences of Israel’s restrictions on social and health services, as this quite clearly falls beyond its remit. Palestinians in Area C, who lack basic services and who endure Israeli settler violence every day, are in this position because of a grave “protection failure” by the international community. In these parts of the West Bank, it is Israel, and by implication the international community, that must answer for the fact that women are unable to access services that will protect them (UN Women, 2020: 14).xvii

While the PA is unable to address the systematic and structural nature of this violence, it could at the very least introduce legislation that extends legal protection to women. In a lawless environment, violence against women is settled by a customary law that frequently absolves perpetrators of their crimes. While I fully concur with al-Azm’s claim that the progress of Arab society depends on women’s liberation, I would stress that the current imperative is to create an environment where women are free from violence. This is a limited agenda, however, and in the longer term the emphasis must expand to building Palestinian institutions, democracy, and gender equality. Yet this expansive agenda is quite clearly incompatible with, and in many respects fundamentally opposed to, colonial control.

Israel, the PA, and the international community are all implicated in the ongoing failure to implement Resolution 1325 in the OPT. The failure to protect women from violence should largely be placed on Israel, as it is impossible to understand the situation of Palestinian women within Palestinian society without referring to the wider colonial context. I would suggest that the international community is complicit in the situation in Area C, as it has tacitly condoned a situation where Palestinian women (and men) are subject to routine and systematic violence that is exerted with a clear political (colonial) aim in mind.

Women’s participation in peace negotiations is problematic, as the question is preempted by the assumption that “peace” is a universal good. In the Palestinian context, of course, this is not the case, as it is given pejorative overtones and connotations. The Palestinian rejection of “normalization” means that the focus of Palestinian women is more likely to be on internal capacity-building that will strengthen and enhance the ability of Palestinians to resist occupation.

The failure to ensure the broad participation of Palestinian women is in large part the responsibility of the PA, as this is essentially an internal question of Palestinian governance. There are clear historical precedents for women’s participation in Palestinian politics, many of which were established in the first intifada. A large number of contemporary democratic deficits can be traced back to the accords, which were negotiated in secret and in many respects reinforced, and even introduced, antidemocratic tendencies. Shortcomings in women’s participation and representation should be perceived in this wider context, although it is also important to

acknowledge the economic and cultural factors that may inhibit women’s participation, both in politics and in wider Palestinian society.

________________________________________

Endnotes

i Al-Azm, S., 2011. Self-criticism after the defeat. Saqi books (Kindle Edition).

ii Nadia Hijjab, Women are Citizens Too: The Laws of the State, the Lives of Women (2002), Regional Bureau for Arab States, UNDP, Casablanca, July 2002. https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/files/Gender-Pub-women%20are%20citizens%20too-EN.pdf

iii Suheir Azzouni Mahshi, "A Free Palestinian, a Free Woman," Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture 2, no. 3 (1995).

iv Azzouni, S. (2010, March 3). Women’s rights in the Middle East and North Africa 2010—Palestine (Palestinian Authority and Israeli Occupied Territory). Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?docid=4b99011fb

v Hammami, Rema (1995), “NGOs: the professionalisation of politics,” Race and Class, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 51-63.

vi UNICEF Occupied Palestinian Territory, Education in Emergencies and Post-crisis Transition, 2010 Report Evaluation, June, 2011.

vii Jerusalem Media and Communication Centre (JMCC). On Palestinian Attitudes Towards Politics and Media, JMCC Public Opinion Polls, No. 33, October, 1999

viii Naser-Najjab, Nadia, 2020. Dialogue in Palestine: The People-to-People Diplomacy Programme and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Bloomsbury Publishing.

ix www.pngo.net.

x www.batshalom.org accessed 25 February 2004

xi Najjar, Farah. Domestic abuse against Palestinian women soars. Al-Jazeera, 20 April, 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/4/20/domestic-abuse-againstpalestinian-women-soars

xii See, https://www.wclac.org/

xiii UNFPA, State of Palestine Office. Seeking Protection: Survival of Sexual Violence and their Access to Services in Palestine. February, 2020.

xiv Palestinian Working Woman Society for Development (PWWSD). In-depth Assessment of Women’s Access to and Ownership of Land and Productive Resources in the occupied Palestinian territory. April 2020.

xv CARE Palestine- West Bank/Gaza. 2020. A summary of Early Gender-Based Violence in COVID-19. Policy Brief. Palestine. April 2020. http://www.careevaluations.org/wp-content/uploads/CARE-Palestine-WBG-RGA-Summary-04052020.pdf

xvi UN Women. Gender Alert: Needs of Women, Girls, Boys and Men in Humanitarian Action in Palestine. August, 2020

xvii UN Women. Gender Alert: Needs of Women, Girls, Boys and Men in Humanitarian Action in Palestine. August, 2020