Fundamentalism is a form of radicalism that can be found in any society, and the term can be applied to both individuals and groups. It is a set of beliefs that drive people toward intolerance, hatred, and rejection of and contempt for “the other.” Jewish fundamentalism began to emerge in Israel following the 1967 war, which religious nationalists considered to be a God-given miraculous victory, and particularly after the founding of Gush Emunim (the Bloc of the Faithful) in 1974. Since then, this trend has had

immense implications for the Middle East, the Arab and Islamic worlds and, primarily, the Palestinian people. Against this background, Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and his peace deal didn’t come out of the blue.

During its 70 years of existence, Israel has fought six wars that have reshaped the political and geographical map of the region. This reinforced Jewish fundamentalism, as the state was perceived as the fulfillment of the prophecy of “God’s chosen people” and their reclaim of the “Promised Land” by both religious nationalists and Christian evangelical fundamentalists.

Elements of Jewish fundamentalism can be found in Western societies as well as in the Jewish community in Israel. Needless to say, the Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) are the sector that suffers the most from Jewish messianic settler fundamentalism. This trend directs its aggression against everything that is Palestinian through biblical settler-colonialist considerations, such as the belief that God promised the entire land to the Jewish people and that the Jews are entitled to it as compensation for centuries of suffering in the Diaspora and particularly because of the Holocaust. Thus, the fundamentalist Jews justify their version of Zionism as beyond question and its actions are beyond accountability.

Hidden Roots of Fundamentalism in Israeli Politics

The Egyptian scholar, author and thinker Abd AlwahhabAl-Messiri1 defines the sociology of knowledge as a science that examines the relationship between ideas and society: How these ideas evolve, how some are adopted collectively by certain groups and social sectors, and how they are harmonized to form a collective, shared model that embodies the group interests and vision of the universe or its political and economic behavior.

In his book The Jewish State,2 Theodor Herzl addressed the sufferings of the Jews at the hands of the Catholic Church in Europe and the Catholics’ discrimination against Jews, which led to their expulsion from England, France and Germany and, in centuries before that, from Spain. Only after the appearance of Martin Luther did the Catholic Church in Europe become less dominant. Eventually Europe was divided between two camps. One followed Martin Luther’s belief that the reference should be only to the Holy Book, while the Protestant Church started reading the Old Testament about the prophets of Israel, their heroes, which included some practices of killing of non-Jews according to the instructions of God.3

Yitzhak Shapira is an Israeli rabbi who lived in the West Bank Israeli settlement Yitzhar and is head of the Od Yosef Chai Yeshiva. In 2009, he published a book, The King's Torah, in which he writes that it is permissible for Jews to kill non-Jews (including children) who threaten the lives of Jews.4

According to Jewish fundamentalist interpretation of Zionism, which runs counter to that of the secular founders of modern Zionism, the creation of Israel was based upon the prophecies of the Torah that they are “God’s chosen people” and therefore he granted them the “Promised Land” — to realize the legend of survival of those whom God had chosen to rule humankind and spread their principles and values around the world.5

Thus, the Western commitment led by the United States to support the creation of a Jewish Homeland and, after 1967, its military superiority in the Middle East is seen by Christian evangelical fundamentalists as an aspiration to achieve the Prophecy of Mount Megiddo. It is therefore possible to view how the Zionist project evolved in Palestine towards achieving what Ilan Pappe6 describes as restructuring Judaism as “national identity” — in spite of the colonial character that accompanied and still accompanies the Zionist enterprise in Palestine, which paved the way for Israel to seek various methods of ethnic cleansing in the Palestine.

Political sociologists in Israel agree on the great role of the military victories that Israel achieved over the Arab states in 1967 and what resulted from it of the occupation of the West Bank, Jerusalem, Golan Heights, Gaza Strip and the Sinai desert, which Jewish fundamentalists consider a miracle of God, created an environment suitable for the growth of Jewish fundamentalism growth. The followers of Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Cook, son of the former chief rabbi of Israel at the Merkaz Harav seminary, saw it as fulfilling the prophecies of the Torah towards achieving salvation and led to the rise of the “Messiah.” Rabbi Moshe Levinger, the godfather of settlements activities in Hebron, said that “all that is happening [is] only ‘God’s will’ to liberate big portions of our lands.”

The Zionist ideology, in its essence, according to right-wing leader Menachem Begin’s close associate Chaim Landau, revolves around one fixed idea, and “all of the other values are mere tools in the hands of this absolute,” and he defines this absolute as “the nation.” Early secular Zionist writer Moshe Leib Lilienblum,7 an atheist, agreed with Landau and said that “the whole nation is dearer to us than all the rigid divisions related to Orthodox or liberal matters in religion. There are neither believers nor infidels, but all are children of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob ... because we are all holy whether we are infidels or Orthodox.”8 This “holiness” is related to two contrasting concepts in its depth: first, “Judaism as a heavenly religion,” and second, “Zionism as an earthly political ideology,” with the first becoming a servant of the second. Most prominent Zionist thinkers such as Theodor Herzl, Leon Pinsker, Simon Maximillian Nordau, Nachman Syrkin and Dov Ber Borochov were a product of their contemporary European era, an era marked with secularism and atheism, interested in what is materialistic and quantitative, and they paid little attention to Judaism as a religion and even showed clear hostility to it.

What can be concluded from the contradiction between orthodoxy and liberalism is that Judaism is a source of latent energy, through religious preambles, urging the Jews to come to Israel aliyah in advent for the creation of the Zionist national Jewish state. To fulfill the Zionist ideology through a comprehensive solution that combines “holiness” and “nationalism.” In order to achieve its goals, Zionist theorists believed in employing violence against enemies of the Zionist project when considered necessary.

This radical approach is exacerbated when a religious political ideology is applied to it by its theorists to grant it ‘divine’ legitimacy; and it even gets more dangerously among its simple-minded followers.

This confirms that fundamentalism is not an exclusive domain of Arab and Islamic societies, but that all societies suffered or still suffer from various forms of political and religious fundamentalism, whether it is in thought, belief, practice or behavior. The Arab thinker Mohammad Abed Aljabiri was indeed truthful when he said that “in every ideology there is always a slant for fundamentalism and extremism.”

Therefore, fundamentalism appears in the 20th century to the 21st century to be very expressive of religious developments that were the product of accumulative outputs of a fundamentalist radical thought, leading to what to social scientists call battling with modern society. This is what we see before us today in the Israeli political establishment’s practices, after the failure of the secularism that the pioneer Zionists hoped to achieve when they came to Palestine. It is the same practices that the Israeli government

used recently to give legitimacy to annexing settlements in the West Bank to Israel, in the context of Trump’s peace plain possible exchange for lands, in the triangle area. According to Professor Yousif Jabarin, an urban planner, after careful examination of the borders proposed in Trump’s “peace deal” — parallel to the Jezreel Valley9 (Marj Ibn Amer) along the Triangle borders — is nothing but a “transfer plan” to move people, without their lands, which will be taken over and is estimated at approximately 200,000 dunums, as part of an Israeli scheme to transform all targeted cities and towns along the Green Line into a new form of ghetto, to deprive the people of their citizenship and land. While bending to Jewish fundamentalist pressure to expand settlement activities in geographical areas thought to have biblical history to gain as much as possible during Trump’s mandate as U.S. president — whom right-wing Israelis view as God’s gift to achieve their geographic, political and economic greed.10

Although some sociologists described the Israeli society as a pluralistic society, this pluralism in Israel in particular and for several reasons has constituted a fertile environment for tension and clashes between ethnic and racial groups, something that urged social scientists such as (Horowitz and Lissak,1989)11 to identify five major rifts in the Israeli society: national (Arabs-Jews), religious (religious-secular), sectarian (Sefardi-Ashkenazi), social class (poor-rich) and ideological (right-left). Social scientists believe that the most dangerous among them is the national rift, but the reality of the situation on the ground and what the fundamental practices have produced over the last two decades indicate that the religious rift is the most dangerous, based on the premise that the gap between religious doctrine and secular ideological thought is so wide that it is impossible to bridge between them. This shows the gradual shifts in Israel towards the extreme right in those decades that reached its peak during the peace process that led to the

assassination of Yitzhak Rabin — a rise in incitements against a negotiated settlement with the Palestinians and against those who supported it, which widened the religious rift and resulted in violence on several occasions. It is worthwhile to distinguish here between the “national messianic sentiment” that believes in the salvation of the Jewish people and work to attain it, which is mainly represented by the fundamentalist Gush Emunim movement, and the groups of the ultra-Orthodox (religious or religiously observant) — “Haredi groups” whose main concern is fulfilling religious duties and prayers and somehow isolated from the main social and political stream.

David Hirst12 claims that “the roots of violence in the Middle East belong to “Jewish fundamentalism,” and criticizes the western negligence of its dangers as applying double-standards, especially that the West always fought Islamic fundamentalism and considered it as the enemy that took the place of communism.”

Jewish fundamentalism casts the shadow of its power over domestic and foreign policy of Israel, where it meets with the U.S. “messianic fundamentalism” and has a weight that greatly influences the formulation of U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East and its relation to Arab countries, and Palestinians in particular. This power has become embodied in the Jewish-Israeli culture, and the concepts of the joint identity became leaning towards ethnicism, in contrast to the prevailing impression that the groups of the ultra-Orthodox — “Haredi” Jews — are not concerned who controls the government as much as their materialistic interests and concerns, However, according to a “religious rulings” by some national-religious fundamentalist rabbis, those who are considered as ‘left-wing’ to be treated under the concept of “law of the pursuer” — Din Rodef,13 which allows killing of Jews without trial. Such rulings led to the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, but this extreme shift towards fundamentalist fascist right, and change in the rules of the game in the context of the on-going debate about definitions, such as whether the “state” should adopt the definition of identity or adhere to its administrative functions that was established to fulfill. The decision was in favor of the former at the expense of the latter, and the outcome was approving the racist nation-state law, which necessarily leads to justification of “ethnic transfer” attempts. Only in that way is it possible to read and understand the dimensions of fundamentalism and the implications of Trump’s peace plan.

Conclusions

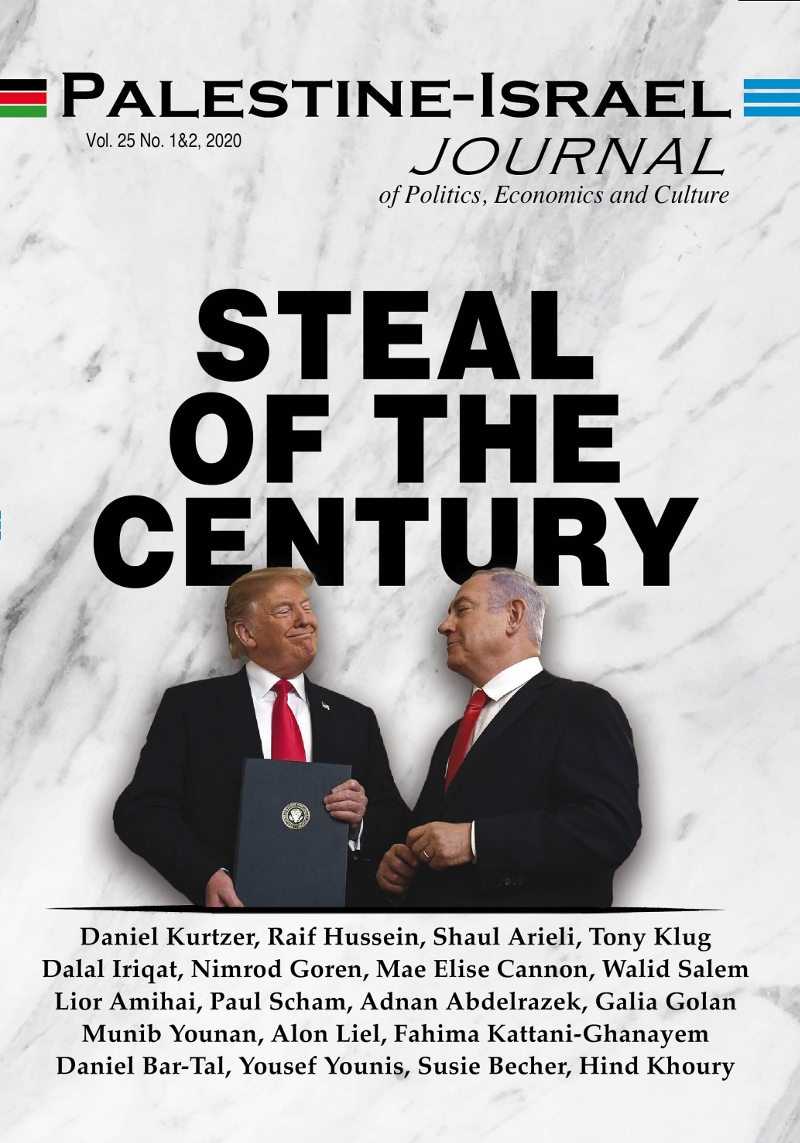

If the point of view of some American diplomats that Trump’s personality has brought about a flagrant change in the U.S. foreign policy in regard to the Arab-Israeli conflict, and the reference here to the U.S. declared policy in the context of what is called international relations, then all of the above confirms that Trump didn’t make any significant changes. But he expressed the messianic fundamentalism that supported him to become president of the strongest country in the world. And what his Christian fundamentalist vice president, Michael Pence, declared recently reaffirms that: “we support Israel because of the historical divine promise and those who support Israel will receive the blessings of God.”

The fact that the president handed the Middle East conflict file to a team of fundamentalist Orthodox American Jews such as his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman and special envoy Jason Greenblatt shows the strong bond between the messianic fundamentalist groups in Tel Aviv and Washington, DC. Thus, it is possible to see the fundamentalism roots of the “Deal of the Century” peace plan. Unfortunately, however, the plan disrespects the international legitimacy resolutions related to the conflict and completely undermines the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people.

Endnotes

1 El-Messiri, A. W., 1992.The Zionist Ideology: A case study in sociology of Knowledge. 2 ed. AlamAlmaarefa

2 Herzl, T., 2007. The Jewish State. s.l.:Dar El Shorouk.

3 The Bible, The Book of Deuteronomy Chapter 7:16 דּבְרִָים [Online] Available at: https://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt0507.htm

4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yitzhak_Shapira

5 The Bible, Genesis1-5 :12 בְּרֵאשִׁית [Online] Available at: https://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt0112.htm

6 Pappé, I., 2006. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. s.l.:Oneworld Publications.

7 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moshe_Leib_Lilienblum

8 El-Messiri, A. W., 1992.The Zionist Ideology: A case study in sociology of Knowledge. 2 ed. AlamAlmaarefa

9 Also known as the Valley of Megiddo

10 Afifi, M., 2006. Fundamentalism. An old Jewish industry. [Online] Available at: https://annabaa.org/nbanews/01/46.htm

11 Horowitz Dan and LissakMoshe.1989.Trouble in Utopia: The Overburdened Polity of Israel. Albany،NY.

12 Hirst, D., 2003. The Gun and the Olive Branch. 3rd ed. s.l.:Nation Books.

13 “law of the pursuer” -“Din Rodef”, in traditional Jewish law, is one who is “pursuing” another to murder him or her. According to Jewish law, such a person must be killed by any bystander after being warned to stop and refusing. The source for this law is the Tractate Sanhedrin in the Babylonian Talmud, page 73a https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rodef

Sources

- Lustick, I. S., 1987. Israel's Dangerous Fundamentalists. Foreign Policy, Number 68(Fall), pp. pp. 118-139. [On line] Available at: https://www.webcitation.org/queryurl=http://www.geocities.com/alabasters_archive/dangerous_fundamentalists.html&date=2009-10-25+12:14:38

- Israel Shahak and Norton Mezvinsky, Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel (Pluto Middle Eastern Series), Pluto Press (UK), October, 1999, hardcover, 176 pages, ISBN0-7453-1281-0; trade paperback, Pluto Press, (UK), October, 1999, ISBN 0-7453-1276-4; 2nd edition with new introduction by Norton Mezvinsky, trade paperback July, 2004, 224 pages

- Rafik Awad, Ahmed. Pillar of the Lord's Throne: on Religion and Politics in Israel, Amman 2011

- El-Messiri, A. W., 2018. Encyclopedia of the Jews, judaism and Zionism. VOL. II.7 ed. Cairo: Dar El Shorouk

- Muhammad al-Masri and Ahmed Rafiq Awad, 2019. The Prospects of Extremism in Israel. Amman: Al Dar Al Ahlia Bookstore.