Although I live in Washington, DC, less than 3 miles from the White House lawn, on September 13, 1993 I watched the signing ceremony of the Oslo Accords from Jerusalem. I took a tiny bit of ownership in watching the peace process succeeding (as I thought then) before my eyes, as I had set up the first DC office of Americans for Peace Now in 1989 and had spent a year and a half lobbying for peace — in those pre-Oslo days when even Peace Now was afraid to openly support two states. I had little doubt that — as many friends put it — “we won” and, except for inevitable bumps on the road, Israeli-Palestinian peace was (almost) assured. Later that evening, I saw groups of Palestinians mingling with Israelis around the “seam” line, some carrying PLO flags that had been strictly illegal until then.

As a historian, it made sense to me that peace was breaking out. The old world order was crumbling, democracy seemed on the ascendant and the generation of 1948 was in its final years. The (first) intifada had taught Israelis that the Palestinians would not accept occupation forever — while time and repeated failure had taught Palestinians that Israel was there to stay.

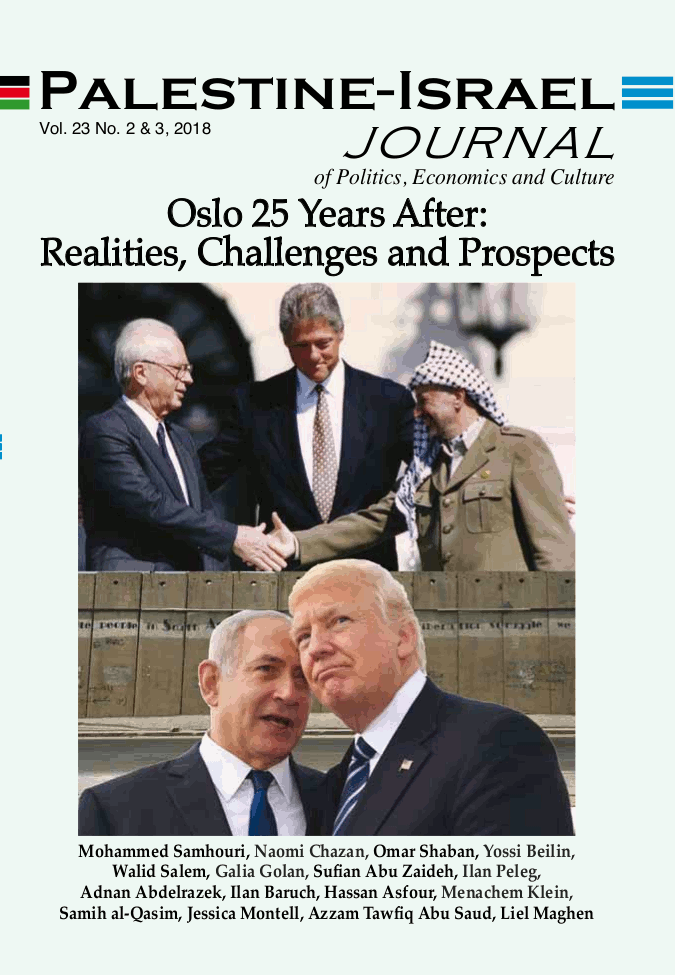

Twenty-five years later, I still think my analysis was correct, that peace could have and should have followed the ceremony on the White House lawn. Why didn’t it?

Most historians eventually conclude that history is a constantly shifting balance between contingency and deep forces. We prefer to analyze and focus on the latter because there is little to say about contingency — which means simply chance, happenstance and luck, both bad and good. And deep forces undoubtedly do exist and shape history. But history is not an experimental (or any kind of) science; we can’t replay events adding or subtracting a single variable. It’s very hard to accept that a historic process can be wrecked by the shots of a Goldstein or Amir, for example. We’d rather see them as the expression of deep, unstoppable processes.

Nevertheless, I continue to hold to the unfashionable view that Oslo should have worked and that peace between Israelis and Palestinians was more than possible; it was on the road to success. Why did it get hopelessly lost in the woods and run into a seemingly immovable barrier?

Half a dozen suggestions:

- • Baruch Goldstein

- • Yigal Amir

- • The errant artillery shell that killed 97 women and children during Operation Grapes of Wrath

- • The 50,000 vote margin that elected Bibi Netanyahu over Shimon Peres in 1996

- • Har Homa (Jabel Abu Ghneim)

- • Netanyahu’s obduracy

- • Yasir Arafat’s unquenchable desire to be all things to all people

I think one of the factors above or some combination of them are to blame, rather than the deeper and weightier reasons most Israeli and Palestinians offer, such as:

- • Israel always intended to perpetuate the occupation with a puppet Palestinian leadership

Or

- • Palestinians never accepted Israel; the whole process was a trick and a lie

I have spent most of the subsequent 25 years working with Israeli and Palestinian organizations on peace projects in Jerusalem and studying, writing and teaching about the history and narratives of the conflict in Washington and Maryland. The narratives are indeed important; they have a major role in inhibiting trust and creating suspicion. They go a long way toward explaining why now, in the summer of 2018, peace seems impossibly far off — much farther than in the summer of 1993. But narratives are ultimately stories; they didn’t cause the conflict — and acknowledging the narrative of the “other” won’t end it. It is human actions that provide causation, such as those listed above.

Peace is now much more difficult because both sides have a tough “once bitten, twice shy” skin that is seemingly impenetrable. Neither side can see the other with anything but maximum suspicion and lack of trust. And the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which once seemed the key to Middle East peace, is now just one of many intersecting fault lines — and not necessarily fundamental to solving anything else.

After Camp David in 2000, there was a cottage industry for a while coming up with the “lessons of Oslo,” in which I participated. Now, I am much more skeptical that Oslo has much to teach us. I utterly reject that there was one big villain or one side to blame. Rather, the Oslo baby is dead, so let’s throw it out with the bathwater and start over again, because peace is indeed possible — just much tougher to achieve than before.