It’s hard to be optimistic about the hopes for any sort of solution to the Israeli/Palestinian conflict that offers the latter even a modicum of self-determination and collective dignity. Virtually everywhere one looks, apartheid, de facto annexation and an increasing possibility of a mass population transfer appear to be underway on the Israeli side, whose most extreme right-wing government ever is clearly moving in an anti-democratic, theocratic and even more militant direction. The Palestinians, led by Fateh on the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza appear all but powerless to resist.

In the United States, Israel has sacrificed much of the good will it has long enjoyed among large segments of the population, including especially American Jews. And yes, Democrats, young people, leftists and liberals, and Jews who answer to all three descriptions have all come to sympathize, to varying degrees, with the cause of Palestinian liberation. Due, however, to the rock-solid support Israel enjoys among Republican Christian Zionists, the “pro-Israel” organizations that lobby Congress and the wealthy and the conservative Christians and Jews who fund these organizations, these developments are not likely to result in any fundamental changes in U.S. policy toward the conflict. One only has to compare the Zionists’ original struggle for statehood in the U.S.—and the historically unprecedented support it received from American Jews and their Christian allies—to the situation currently facing the Palestinians seeking to build support for their—one hopes—future homeland, is to invite even more pessimism into this political equation.

The most important fact to remember about the debate over what to do about Palestine in 1948 was the shock of the discovery of the Holocaust fewer than three years earlier; a discovery that energized Jews and shamed Christians. As the Zionist firebrand Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver put it, “Our six million dead are a tragic commentary on the state of Christian morality and the responsiveness of Christian conscience.”

The American Liberals Chose the Zionists

At the dawn of the debate over Jewish statehood, liberals made their choice, and they chose the Zionists. The Nation’s editor-in-chief, Freda Kirchwey, discovered what she called “the miracle of Jewish Palestine”— the Jewish men and women who had emigrated to Palestine to help shape the future of the Zionist state, she said, were “’free’ in the full moral meaning of the word.” They had resisted imperialist interests driven by “oil and the expectation of war; oil and the fear of Russia; oil and the shortage in America; oil and profits.” America’s other leading liberal publication, The New Republic, covered Palestine much as The Nation did, though with less intensity. Its early coverage was heavily critical of the British. In December 1946, former vice president Henry Wallace took over as the magazine’s editor before quitting, in July 1948, to run for president as a far-left challenger to Truman. While at TNR, he took a tour of Palestine in the winter of 1946–1947 and returned home to announce that “Jewish pioneers” in Palestine were “building a new society” there. Wallace found the Zionists in Palestine ready to teach “new lessons and prov[e] new truths for the benefit of all mankind.” They sought to do this, moreover, not from a “somber spirit of sacrifice,” but with “a spirit of joy, springing from their realization that they are rebuilding their ancient nation.”

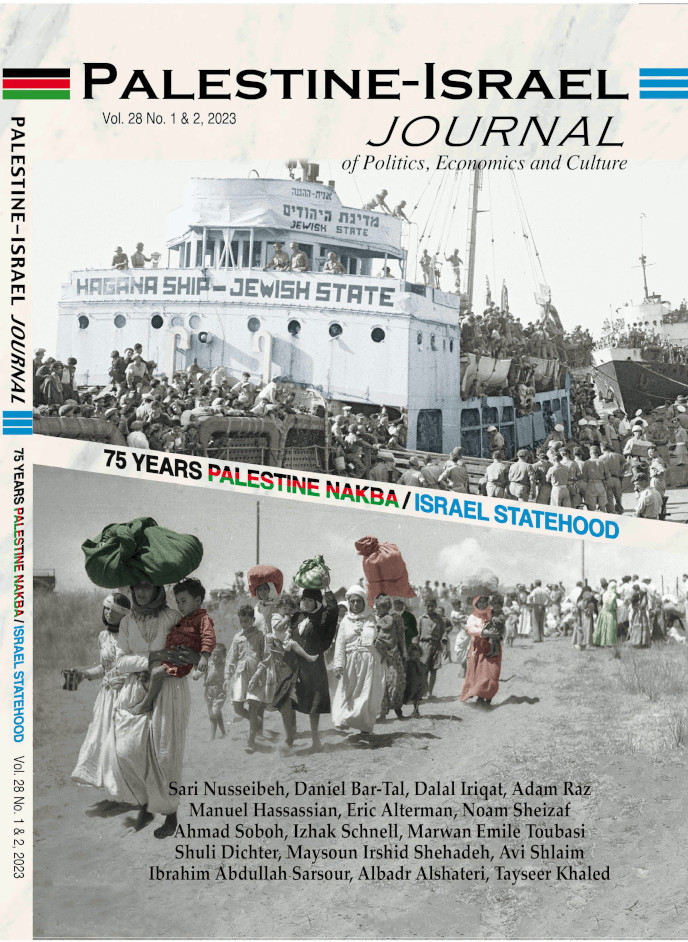

Also reporting from Palestine for The New Republic was the legendary leftist journalist I. F. Stone. Working for an ever-changing series of leftwing publications, Stone sought to combine the human drama he was witnessing with his Marxist-infused interpretation of world history. He published a series of moving newspaper columns later collected in the now classic work Underground to Palestine, and later a celebratory book with the photographer Robert Capa titled This Is Israel. Stone traveled on the crowded, barely seaworthy vessels secured by the Zionists to smuggle refugees from Europe to Palestine, eluding British warships on the way. He sought “to provide a picture of their trials and their aspirations in the hope that goodpeople, Jewish and non-Jewish, might be moved to help them.” More than any other contemporary journalist, he succeeded in capturing the desperation of Zionist pioneers as well as their passionate optimism. Stone became enraptured by the “tremendous vitality” of those who just months earlier had been “ragged and homeless” survivors of Nazism, and who were now building Jewish Palestine. “In the desert, on the barren mountains,” and in “once malarial marshes,” he wrote, “the Jews have done and are doing what seemed to reasonable men the impossible. Nowhere in the world have human beings surpassed what the Jewish colonists have accomplished in Palestine, and the consciousness of achievement, the sense of things growing, the exhilarating atmosphere of a great common effort infuses [their daily lives].”

Ben-Gurion and Truman

With the political wind at their backs, the Zionists made their case eloquently, if not always honestly. Future Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion told The United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) in 1947, “There will not only be peace between us and Arabs, there will be an alliance between us and Arabs, there will be friendship.” But Ben-Gurion himself knew this to be nonsense. In fact, in a 1937 letter to his son, he had written, “A partial Jewish state is not the end, but only the beginning.... We must expel Arabs and take their places, if necessary ... with the force at our disposal.”

American Jews were an enormous resource for the Zionists, and they understood this. As early as 1941, Ben-Gurion had observed, “We must storm the American people, the press, the congress—Senate and House of Representatives, the churches, the union leaders, the intellectuals—and when these will be with us, the government will be with us.” He was not wrong. By the end of 1945, 41 governors and state legislatures had signed letters calling on Truman “to open the doors of Palestine.” Fully 27 speeches on Palestine were heard in the Senate in just one 48 hour period in February 1947, with another 34 senators adding statements of support to the Congressional Record. Mailings ran into the many millions: one Connecticut town with just 1,500 Jews managed to send 12,000 preprinted pro-Zionist postcards to U.S. officials. That same year, there were mass demonstrations in 30 cities in a single month. Together with the countless other municipalities that sent the same message, these pro-Zionist politicians and voices could be calculated to represent 90 percent of the U.S. population at the time. The combination of the pain and guilt inspired by the Holocaust, combined with the heroic narrative of Zionists being reported out of Palestine, all-but overwhelmed any potential alternative political position.

President Truman, Franklin Roosevelt’s successor, was no Zionist. He thought that nations based on religion and/or ethnic exclusivity belonged to the past. Yet Truman was also deeply moved by the increasingly desperate plight of the hundreds of thousands of stateless Jewish refugees— survivors of Nazi death factories, or those who had emerged from hiding places in attics and the like—who had now been shunted off to squalid, unsanitary Displaced Persons (DP) camps. Truman’s “basic approach,” as he described it in his memoir, “was that the long-range fate of Palestine was the kind of problem we had the U.N. for. For the immediate future, however, some aid was needed for the Jews in Europe to find a place to live in decency.” He hoped to provide such aid, however, without simultaneously granting the Zionist demand for Jewish sovereignty. He would find that this was impossible.

Truman’s heartfelt sympathy for the refugees’ plight, together with his admiration for the people of the Old Testament, constantly tugged at his conscience. His national security team felt otherwise, though, concerned that the establishment of a Jewish state would mean problems for the United States in the region in the future, and logically, Truman knew this to be true. But his political instincts, along with those of his political advisers, also pulled in the direction of the Zionists. New York City, where half of America’s Jews already lived, was crucial to Democrats in any national election. A pattern established itself relatively quickly. When the president found himself with a choice between acceding to the Zionists’ demands or siding with his own national security and diplomatic advisers, he would let loose with a fusillade of complaints about how infuriating the former were being before he ended up siding with them. British Foreign Secretary Bevin recalled Truman saying, just before the 1946 election: “They [the Jews] somehow expect me to fulfill all the prophecies of the prophets. I tell them sometimes that I can no more fulfill all the prophecies of Ezekiel than I can of that other great Jew, Karl Marx.”

Truman’s closest friends and confidants worked hardly less relentlessly on behalf of the Zionists than the Zionists themselves. The president was heard musing not long before the 1948 election, “I am in a tough spot. The Jews are bringing all kinds of pressure on me to support the partition of Palestine and the establishment of a Jewish state. On the other hand, the State Department is adamantly opposed to this. I have two Jewish assistants on my staff, David Niles and Max Lowenthal. Whenever I try to talk to them about Palestine, they soon burst into tears.”

Truman had good reason to be concerned. Not only had his likely opponent in the 1948 election, Thomas Dewey, a strong Zionist supporter, been the New York state’s governor, but New York City looked to be fertile ground for Henry Wallace, who was challenging Truman from the left on the 1948 Progressive Party ticket. Whenever the administration appeared to deviate from Truman’s stated pro-Zionist position, Wallace would speak of the “gift of a million votes” for him. Truman needed little convincing on this point. As early as 1945, he explained to four U.S. ambassadors to Arab countries that whatever their objections to a pro-Zionist policy, he had “to answer to hundreds of thousands who are anxious for the success of Zionism”: “I do not have hundreds of thousands of Arabs among my constituents.”

No Palestinian Narrative and Voice in the Mainstream Media

I do not need to explain to readers of this journal that in the 75 years since these events took place, the Israelis and their supporters in the U.S. have successfully created a mythical picture, not only of the events leading up to 1948 but of almost every aspect of Israeli/Palestinian relations ever since. The word “Nakba” did not even appear in The New York Times until

1998, Supporters of Israel have also dominated debate on the nation's op-ed pages. Aside from a brief period when the paper looked to the late Edward Said to give voice to the Palestinians anguish, the parameters of the page’s discourse have, with just a few exceptions from guest contributors, been defined by voices that ranged from “liberal Zionist” rightward. According to the research of Maha Nassar, a Professor of Middle Eastern and North African Studies at the University of Arizona, published in 2020, during the previous fifty years fewer than two percent of the nearly 2,500 op-ed articles published in The New York Times that addressed Palestinians and the issue facing them were authored by Palestinians. This was twice the percentage achieved by The Washington Post. In The New Republic during this fifty-year period, the magazine published over 500 articles on the subject, and the number of Palestinians invited to contribute totaled zero.

Palestinians Need to Understand How the American Political System Works

The Palestinians and their supporters have never found their footing in the debate over U.S. policy. Even in recent years when their cause has made significant strides in leftist circles and on elite U.S. college campuses - where their supporters no doubt significantly outnumber Israel’s partisans - they have not succeeded in challenging Israel’s (self-defined) security needs as the primary purpose of U.S. foreign policy, regardless of its implications for the lives of the Palestinians who must suffer as result.

A part of the problem is the fact that even in the decades leading to their catastrophe of 1948, the Palestinians had rarely demonstrated a willingness to share the land as the Zionists did (if perhaps less than sincerely). What’s more they’ve shown little interest in the actual nuts and bolts of the U.S. political system. In an interview published in the Journal of Palestine Studies, Noam Chomsky tells of attending meetings with senior PLO officials during the early 1970s at the invitation of Edward Said. As Chomsky recalled, Said hoped to increase ties between PLO officials and “people who were sympathetic to the Palestinians but critical of their policies.” Chomsky found these meetings “pointless.” “We would go up to their suite at the Plaza, one of the fanciest hotels in New York, and basically just sit there listening to their speeches about how they were leading the world revolutionary movement, and so on and so forth.” Chomsky discerned in the PLO “a fundamental misunderstanding of how a democratic society works. . . . But the Palestinian leadership simply failed to comprehend this. If they had been honest and said, ‘Look, we are fundamentally nationalists, we would like to run our own affairs, elect our own mayors, get the occupation off our backs,’ it would have been easy to organize, and they could have had enormous public support. But if you come to the United States holding your Kalashnikov and saying we are organizing a worldwide revolutionary movement, well, that’s not the way to get public support here.”

Only Five Percent of Americans Support BDS

Most of the political energy of the Palestinian movement and its supporters in recent years has been devoted to building support for the “Boycott, Divest and Sanction” (BDS) movement directed against Israel. Again, while it has achieved some success among college students and progressive activists, judged by its stated goals, the BDS movement has been an abject failure. Not a single major American university, corporation, or even labor union has agreed to boycott Israel. Its effect on the Israeli economy has been literally invisible. The BDS movement never did succeed in reaching enough Americans for even a remotely significant number of them to form an opinion on it. According to a May 2022 Pew Research Center survey, just five percent of Americans questioned said they supported the movement (with two percent doing so “strongly”).

The movement produced a profoundly disproportional backlash. BDS supporters found themselves denounced and shunned by almost all mainstream Jewish organizations. At publicly funded universities, local officials often found BDS events an irresistible target. At Brooklyn College, New York State Assemblyman Dov Hikind — who represented a district heavily populated by ultra-Orthodox Jewish constituents—demanded the resignation of the school’s president because of her willingness to allow a joint lecture by BDS founder Omar Barghouti and the pro-BDS literary scholar Judith Butler. Inspired by a lengthy document compiled by the farright Zionist Organization of America, filled with falsehoods, exaggerations, and McCarthyite insinuations, New York state legislators sought to radically cut back funding for Brooklyn’s parent institution, the City University of New York (CUNY). The tactic appeared on the verge of success until a way to have the cut deleted from the final legislation was found in a last-minute budget agreement with Governor Andrew Cuomo.

The story inside the mainstream media is much the same. When, in 2018, the African American CNN commentator Mark Lamont used the BDS slogan in a speech at a United Nations event and called for a “free Palestine from the river to the sea,” the ADL condemned him for allegedly “promot[ing] divisiveness and hate.” He was immediately fired by CNN. In 2021, a young Associated Press reporter found herself fired as well, owing to blog posts she had made as a member of Jewish Voice for Peace and Students for Justice in Palestine while a student at Stanford University—though the issues she covered for AP had nothing to do with the Middle East. The Israelis were so concerned about budding support for Palestinians on campus that their diplomats were known to contact college administrators to try to prevent pro-BDS professors—and even graduate students—from being allowed to teach courses on the conflict.

Is a Change in Attitude Possible?

Thanks to the growth of social media, in other words, for the first time since the debate over Zionism in the United States began, virtually anyone can access a steady stream of reasonably accurate, detailed information about the Israeli/Palestinian conflict from multiple ideological and intellectual perspectives. Yet the political reality has remained largely unchanged. For all the criticism Israel has received in recent years, BDS supporters in Congress number three out of 538. On votes to condition U.S. aid to Israel on its treatment of the Palestinians, as many as eight or nine members of Congress are ready to be counted. President Biden, while on a celebratory visit to Israel in July 2022, attributed the entire phenomenon of Democratic dissent over America’s Israel policies as the politically insignificant “mistake” of just “a few” of the party’s members.

These voices will certainly grow louder soon as Netanyahu’s government demonstrates to Americans that the entire notion of “shared values” between the two nations is a thing of the past. The “new” Israel will likely cause considerable anguish among Israel’s liberal and centrist supporters in Congress, among American Jews and in the public at large. What it will not do, however, is inspire a fundamental rethinking, much less actual change in the direction of U.S. foreign policy toward Israel and Palestine.