Introduction

Identity is a description or a definition of a sense of belonging that is characteristically continuous and dynamic and is forged across unique conditions of time and place. As a result of this continuity and dynamism, individuals possess a variety of identities which are divided into two categories: “innate” (like family or ethnicity) and “acquired” (purposefully chosen by the individual).

The term “hybrid identity” refers primarily to an identity that has undergone transformation, which is the case of the Palestinians who, upon their transition from Palestine to Israel, had to redefine themselves from an ethnic majority to a minority within a national majority-ethnic state. Those Palestinians who survived the war and managed to stay in their homeland within Israel’s borders acquired for the first time a civil identity and became citizens of the State of Israel.

The first comprehensive identity study about young Arabs in Israel was done in 1965-1966 by the sociologists Yohanan Peres and Nira Yuval- Davis. Their conclusions became a milestone toward understanding the complex mechanism that affected not only their self-definition, but also their interactions with the state’s institutions and within their community. Using the word “compartmentalization” to differentiate between the Arab national identity and the Israeli civil identity, the researchers saw these two components as mutually contradictory and the outcome of divergent conflictual forces. In 1976, the sociologists John Hoffman and Nadim Rouhana used the conflict approach to determine that until 1967, the contradiction had been resolved by compartmentalization mechanisms, so that on the emotional level they upheld their Arab nationality while in their day-to-day life they conducted themselves as law-abiding Israeli citizens. However, this balance was broken after the June 1967 War, when the Palestinian component gained more weight, and the Arabs became increasingly hostile toward the state.

After the conflictual identity approach, Rouhana proposed the “accentuated Palestinian identity” approach, whereby the Israeli identity was shunned due to the Jewish-Zionist character of the state, its symbols, laws, institutions, and discriminatory policies toward its Arab citizens. Left with no choice, the Arabs stuck to their alternative national identity, with which they could satisfy their basic need for a complete identity. According to this approach, the Palestinian national identity is accentuated and even exaggerated among Israel’s Arabs, because it is out of balance with their civil identity.

Both the conflictual and the accentuated identity approaches were unacceptable to the sociologist Sammy Smooha. In 1992, he proposed a third model, which he called “non-mutually dependent identities.” In his opinion, elite groups in the Israeli Arab leadership explicitly favored a Palestinian-Israeli identity and aspired to forge a new synthetic identity as a legitimate and pragmatic option for all Arabs in Israel. In his opinion, this move corresponded to the trend in other countries, where minorities developed a “complex and hyphenated” identity combining new and old, such as African American, Italian American, or Israeli American. In an article he wrote in 2001, Smooha emphasized that the very adoption of the non-mutually dependent identity model that sees them as both Israeli and Palestinian poses a great difficulty for Israel’s Arabs. This difficulty originates outside the Israeli-Palestinian-Arab collective, as neither most Jews nor most Palestinians see their nationality as like theirs. In his view, the combination of Palestinian ethno-nationalism and Israeli citizenship has created a “polluted” identity distrusted by both sides due to the very ethnic nature of the Arab-Jewish conflict.

A debate about the three models was not long in coming. In 1993, together with As’ad Ghanem, Rouhana developed the “crisis development approach,” whereby the definition of the state as ethnic-Jewish pushed the Arabs into a multidimensional predicament. In 1997, Majd al-Haj presented his “double periphery situation ” thesis according to which both the civil and national identities are incomplete and have evolved into a sort of detached “half-identities.” In 2002, Eli Reches came up with the “radicalization thesis,” whereby as of 1967, the collective identity of Israel’s Arab citizens began to undergo Palestinization and Islamization, throwing Arabs and Jews into a historical process of mutual alienation and disaffection that could at any time turn into a violent conflict between the two sides. In 2009, Honaida Ghanim proposed the “liminal identity” model, according to which Israel’s Arabs are simultaneously inside and outside opposite fields in both the Israeli and Palestinian space, so that they are neither really included nor completely removed. They oscillate between different layers of identity that do not overlap and at times even clash in a liminal space that is full of contrasts, ambivalence, and conflicts between past and present, civic and political factors, nationalism and politics, modernity and tradition. According to her, liminality turned from a temporary phenomenon into a permanent reality for the Palestinians in Israel after the Nakba in 1948. The official status of the few Palestinians left in Israel was less than full citizens and more than disenfranchised subjects. As they remained both inside and outside their native land, their homeland became someone else’s country, and the Palestinian landscape became the ruin upon which a new state was built.

To sum up, all the aforementioned approaches agree that contradiction, tension, and incompleteness exist between the two collective identities of the Arabs in Israel, the civil and the national. However, they all fail to address the identity of the Arabs of Israel from two points of view, hybridity, and rationality.

On Hybrid Identity

In sociology, hybridity is a concept connected to the post-colonial discourse and to the debate between Edward Said’s “Orientalism,” attributing it to the dichotomy between East and West, and Homi Bhabha's 1994 theory ascribing it to the interaction between Westerners and natives during the colonial period, that redefined personal identities through reciprocal but unequal transcultural influences.

The hybrid identity, like any other identity, describes a sense of belonging comprising constant and fluid components that transform according to unique circumstances of time and place. A hybrid identity emerges within specific local contexts of domination and resistance, as well as acceptance, rejection, imitation, suppression, and more. Such an identity is created from contact between two “others” with different cultures and values: ruler and subject, majority and minority, local and external. It should be noted that hybridization does not see the encounter between these two “others” as a union of separate cultural value systems that merge into one structure, nor as a framework within which a new culture is consciously built from the combination of two or more cultural sources, but as something new that constantly recreates itself.

Bhabha claimed that the cultural space where the identity of both colonizer and colonized are formed is violated by a constant process of mutual hybridization. The “other” is always unconsciously present inside the inner space of each of them, not outside or beyond it, which is why all cultural forms hybridize with each other through rejection, acceptance, and imitation. At the same time, these processes are accelerated and more prominent in the colonized (the Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel, in our case) through colonial mimicry and the aspiration to become a familiar and renewed “other,” dissimilar and similar at the same time. Thus the original cultural identity of the colonized changes and is replaced with a new one: the hybrid model.

Describing the hybridization of the identity of Israel’s Arabs in an interview with Yaakov Agmon in 1997, Emil Habibi said: “The Palestinian people have traits that distinguish them from the other Arab nations, traits which formed and developed through direct conflict with the Zionist enterprise. I say that the Jews in Israel are also beginning to develop unique national characteristics that distinguish them from the rest of the Jews in the world. And the traits of both developed as a result of the influence of one on the other.”

The Hybrid Identity as Realistic

The negotiation that generated the hybrid identity of Israel’s Arabs took place under unique conditions of time and place. In political science and international relations theory, realism is the topmost factor influencing political decision-making. Realism ignores moral or ethical considerations and is based on the idea that states are similar in nature to man: selfish and self-interested, striving to maximize their power and self-preservation. This theory applies to Israel, but it can also apply to political groups and entities, be they collectives or a minority’s political leadership. It is based on the Freudian theory that man’s basic need for power stems primarily from his innate instinct to preserve the self and is motivated by rational considerations that are not necessarily guided by moral principles and ideals.

Citing the need to survive, to self-preserve, and later on to gain power and control, political realism explains why the Palestinians in Israel rushed to enroll in the Population Registry, obtain Israeli identity cards, and take part in the first elections held by the State of Israel already in January 1949, at a time when the wound inflicted by the Nakba was still bleeding profusely and the attendant pain kept reminding them of the balance of powers which left them high and dry, without a national leadership, a roof

over their heads, or protection.

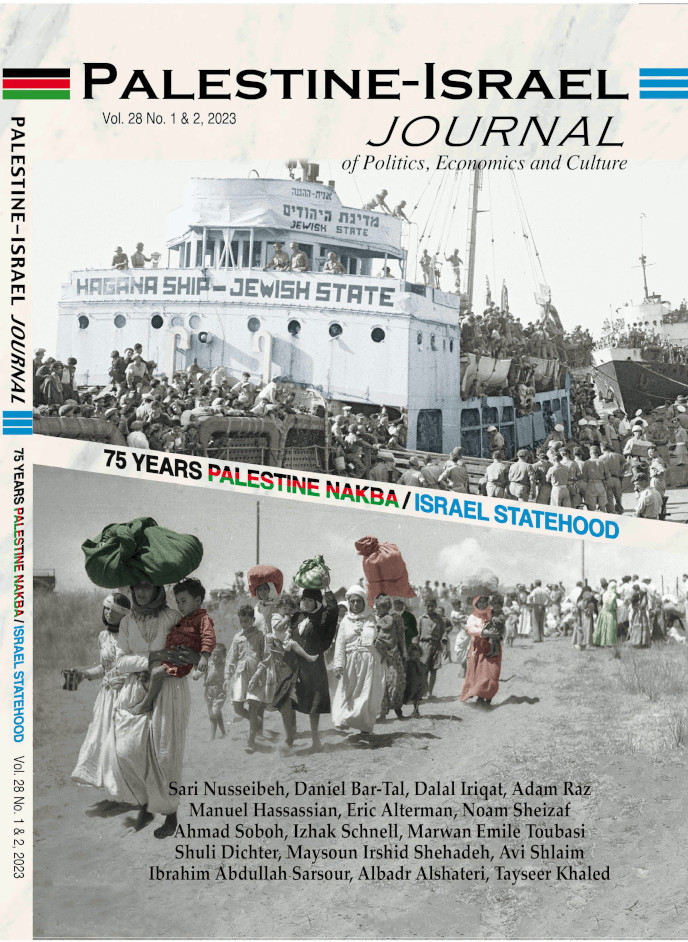

With a bloody war between Jews and Arabs raging in the background, the State of Israel declared its independence on 14 May 1948, and approximately 750,000 Palestinians left their homes and became refugees outside their native land. Some departed even before the war, others during the fighting, and some were forcibly expelled from their places of residence or asked to vacate them temporarily by the Jewish army troops. After the war most of the refugees were not allowed to return to the territory of the State of Israel, while the land and property they left behind were transferred to the use of the Israeli Government through the Absentee Property Law.

After the State of Israel closed its borders, some 156,000 Palestinians remained within its territory. Of these, 25,000-40,000 (35% urban and the rest rural) became “Internally Displaced Persons (IDP)” who relocated to other Arab locales after the Israeli military forces forbade them from returning to their homes. Some IDPs settled in nearby villages, others migrated to localities where their relatives lived, and some were resettled by the state through the Refugee Rehabilitation Authority, which operated from 1949 to 1953.

On the eve of the war, city dwellers (some 445,000) constituted more than a third of the total Arab-Palestinian population (one quarter Christians and the rest Muslims), and about a quarter of them lived in Jaffa and Jerusalem. The urban population, which wielded enormous political, economic, social, and cultural influence, was the first to be hurt by the Nakba and the establishment of the State of Israel. Apart from Nazareth (which remained intact and became a haven for IDPs) and East Jerusalem (30,000 moved out of the western sector), they left their cities and became refugees outside Israel’s borders. The few who survived (3,000 out of 70,000 in Haifa, 4,000 out of 70,000 in Jaffa, 3,000 out of 15,000 in Acre, 1,400 out of 70,000 in Lod and Ramla) were barred from returning to their homes and were relocated to separate neighborhoods, while most of their houses were occupied by new Jewish immigrants. Other cities such as Tiberias (4,700), Bet She’an (6,000), and Safed (2,000) were completely emptied of Arabs (Goren, 2004).

The loss of the national leadership and the educated urban population allowed the emergence of a new dominant group, which took advantage of the opportunity offered by the Israeli Government to introduce itself as an alternative civil and national Palestinian Arab leadership. These were mostly communists led by Tawfik Toubi and Emil Habibi, who had accepted the UN Partition Plan and, already in September 1948, hurried to openly join their Jewish partners in one party and were elected to the Knesset. Seif al- Din al-Zoubi and Amin Jarjoura, clan patriarchs and remnants of Nazareth’s bourgeoisie, joined the first Knesset’s coalition on behalf of the Democratic List of Nazareth, which was a satellite party of Mapai. Rustum Bastouni, the first Arab graduate of the Technion Israel Institute of Technology - became the first Arab member of a left-Zionist party, Mapam, in the 2nd Knesset.

Their consent to become citizens of the Jewish democratic state was not enough for them to integrate with the Jewish citizens and construct their hybrid identity in a free and open space. On the contrary, the hybridization was managed, supervised, restricted, and delineated by two main bodies: the Military Government and the Minister of Minorities. Politicians on behalf of the Israeli government and the Communist Party operated in the same space, assisted later by representatives of the radical Al-Ard Movement in directing the hybrid identity negotiation.

After declaring its independence, Israel’s Provisional State Council invoked the Defense (Emergency) Regulations enacted by the British Mandate in Palestine in 1945, to proclaim (on 19 May 1948) that a state of emergency existed in the country and to impose military rule on specific areas, primarily populated by Arabs. The Military Government’s main mission was to monitor and suppress the national/political activities of the Palestinians who had become citizens of Israel by restricting their freedom of movement and action, controlling the press, and forbidding them from possessing weapons.

The Military Government’s jurisdiction totaled 2,230,000 dunam and was divided into three regions: North, Center (The Triangle), and Negev. It functioned in territories occupied by the Israel Defense Forces which, according to the UN Partition Plan, were to have been included within the Arab state. Its operations were based on the concept that controlling the Arabs would thwart terrorism and protect the Jewish communities. Spatial control is a strategy usually adopted by a central government for the management and fair distribution of a geographic space (urban, rural, inter-urban, etc.) and for security purposes, as well as for limiting the use of land, controlling population growth, overseeing the encounter of populations and impeding their symbiotic relations, creating more favorable conditions for certain ethnic groups at the expense of other groups, and so on. This is exactly what the Israeli government did to the Arabs by means of the Military Government.

The Provisional State Council, which served from 14 May 1948 until 10 March 1949, consisted of the same ministries that had operated under the British Mandate, with the addition of the “Ministry of Minorities.” This was a kind of provisional government dealing with the affairs of the Arab minority, which was established on a temporary basis (it was disbanded in June 1949, after the formation of the first Knesset) and functioned in collaboration with the other government ministries.

The security forces and the army were responsible for enforcing military rule over the Arabs, while the Ministry of Minorities was in charge of organizing their civil life. Based on the Emergency Regulations, Palestinians were prevented from getting to their fields and workplaces and from moving freely in search of a livelihood. These restrictions and physical isolation illustrate the control exercised over the creation of the hybrid identity.

This control was based on the knowledge that the Palestinians would be realistic. As many refugees were homeless or lived in inadequate conditions, a government committee established at the request of the Minister of Minorities was tasked with relocating them within the area under Israeli rule, reuniting family members who were separated at the outset of the war, transfering unemployed Arabs to places where they were guaranteed jobs aiding the construction of the State of Israel, and so on. Despite the demand by army commanders to forgo formalities and confiscate all Arab property in the occupied territories, it was the Ministry of Minorities that was put in charge of the issue.

The Ministry of Minorities had yet another important mission. The searches conducted in the Arab villages during the occupation resulted in throngs of Arabs being concentrated in various camps throughout the country, along with the prisoners of war. The Ministry was inundated with applications from Palestinians, who had overnight become “members of a minority” living within the boundaries of Israeli law, requesting the release of family members detained or held captive by the IDF. The Ministry’s response was based on such criteria as the prisoner’s age, his record, his involvement in anti-Zionist actions, whether he had children or a profession that could be used to strengthen Israel’s economy.

In keeping with the Foreign Ministry’s guidelines banning any return to Israel before the end of the war, such applications were rejected, with some exceptions. According to a report written by the Minister of Minorities, these included “circles known for their long-standing cooperation with the pre-state Jewish Yishuv who were in touch with the Jewish Agency’s political department and the Jewish National Fund, Arab dignitaries who recognize the Israeli state or advocate the idea of an independent government in the Arab part of Western Palestine. The Ministry has counseled minority representatives to agree to assist the army with fighting infiltrations by Arabs and sending them back outside Israel’s borders.” The control exercised by the Ministry of Minorities and the Military Government interfered with the hybrid identity negotiation, especially with acceptance, rejection, and imitation in exchange for survival, security, and maximizing power.

Immediately upon its establishment, Israel proceeded to determine the status of the Palestinians within its boundaries and chose to define them as a community. It adopted the classification of the International Court of Justice in The Hague1 in order to highlight its modernity and multicultural character and to be able to define the Arabs as Israelis and not as Arab nationals. Defining the Arabs as a community would yield multiple benefits: in addition to the above, they would evolve as a fractured community and not merge into one collective against the state. In fact, this was yet another intervention by the state to entrench the identity of the Arabs as a religious community, a definition that affected many areas of their life, such as education, housing, employment, and more.

During and slightly after the Military Government’s tenure (1948- 1970), policymakers tried to inculcate a national-Israeli affiliation into the Arab citizens, by emphasizing Jewish and Hebrew content. But soon, especially after the erasure of the borders and the reencounter between the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip and the Palestinians in Israel following the June 1967 war, they realized that a takeover of the Palestinian identity by the Israeli identity was impossible, and that the two identities would remain separate. Consequently, they tried to weaken the connection to their national identity and to strengthen their connection to their civil- Israeli identity by blurring the national narrative, imposing Hebrew in the public space, demolishing abandoned villages and erecting new buildings on their ruins, emptying school curricula of any national content, imposing censorship on the press and the mass media, presenting Palestinian and Arab culture as shallow and deferent to the culture of the Jewish majority in textbooks, the media, and so on.

During the military rule, the State of Israel became the space where the hybrid identity of the Palestinians living within its borders was constructed. It was an overly complex space, where for the first time they were asked to push aside their identity as Palestinians and redefine themselves as an Arab minority and citizens of the State of Israel. In this space they were subjected to a hostile Military Government, yet they were allowed to exercise their democratic right, participate in equal elections, and vote. At that point in time, participating in the elections was a realistic step for the Palestinians. Every eligible voter received a number and a voting card, which led them to believe that they were registering their presence in the country and becoming part of a powerful political entity where they would be protected.

At a time when they were still having difficulty understanding and speaking the Hebrew language, the Arab MKs who joined the first, second, and third Knesset operated in the political space that was made available to them under the laws of the sovereign, Jewish, and democratic State of Israel and the confines of the military rule governing them and their people. These MKs were asked to join the efforts of the state in shaping the identity of the Arabs. This onerous burden fell on the shoulders of Tawfik Toubi, Emil Habibi, Emil Touma, Tawfik Zayyad, and other leaders of the bi-national Communist Party (MAKI), who assumed their role as the leadership of the national movement. With peaceful means and legal protests, the communist leadership encouraged a struggle against the Israeli authorities because of their unequal policy toward Arab citizens, but, on the other hand, they strove to establish their civil-Israeli identity within the state.

The hybrid struggle, framed as a legal ethno-national and political-civil struggle, has been pursued to this day by almost all Arab political parties (except for Al-Ard, an extreme-left national-Arab political movement established in 1959 by a group of Israeli Arab intellectuals, which aspired to turn Israel into a multinational state).

Due to the top-down manipulations by both the state and political party activists, as well as the acceptance, rejection, and imitation within the hybridization space, some Arabs leaned more toward their ethnonational identity without canceling their identity as Israeli citizens, a second group did the opposite, and a third group adopted a civil-Israeli identity while activating a mechanism of denial and alienation and pushing their ethno-national identity aside. The wish to survive and live safely under a continuous overt and covert threat from the Israeli authorities, the military weakness of the surrounding Arab countries, and other factors hindered the emergence of a distinct and visible group that denies its Israeli civic identity and adheres to its ethno-national identity.

The wish to survive and gain a sense of security and power is also evident in the intergenerational struggle. The younger generation labors to improve their living conditions and move up the social mobility ladder, to raise their socioeconomic status over that of their parents.

Education was and remains the way to achieve social mobility among the Arabs in Israel, as illustrated by the over-the-top festivities that follow the publication of major test scores. At the same time, the desire for social mobility in an unequal ethno-national country places the young generation before the choice of getting an education or acquiring the capital that guarantees a sense of security. Unlike their grandparents and parents, social mobility among the children’s generation has been less sluggish and has evolved along gender lines: the burden of education now falls on women (almost 70% of all Arab students in bachelor, master, and doctoral programs are women), whereas the burden of arduous work and making money fast falls on the men. Such a reality creates an unbalanced society in the education-gender context and induces an internal social struggle, especially because Arabs are a traditional and partly religious society. It should be noted that these findings do not indicate that Arab women hold enviable and influential jobs; despite their education they still have to struggle with policies of inequality, and in most cases they must settle for junior positions in the workplace.

Political realism is the most important factor shaping the identity of the Arabs in Israel. Realistic considerations affect the prominence of their identity circles and such components of hybridization as denial, suppression, acceptance, imitation, rejection, and so on. These translate in practice into a choice of more considered action in the political-civil-social space, where identity is shaped amid prolonged and continuous negotiation.

___________________________________

1 Permanent Court of International Justice, Advisory Opinion No. 17: Greco-Bulgarian 'Communities', 31 July 1930.