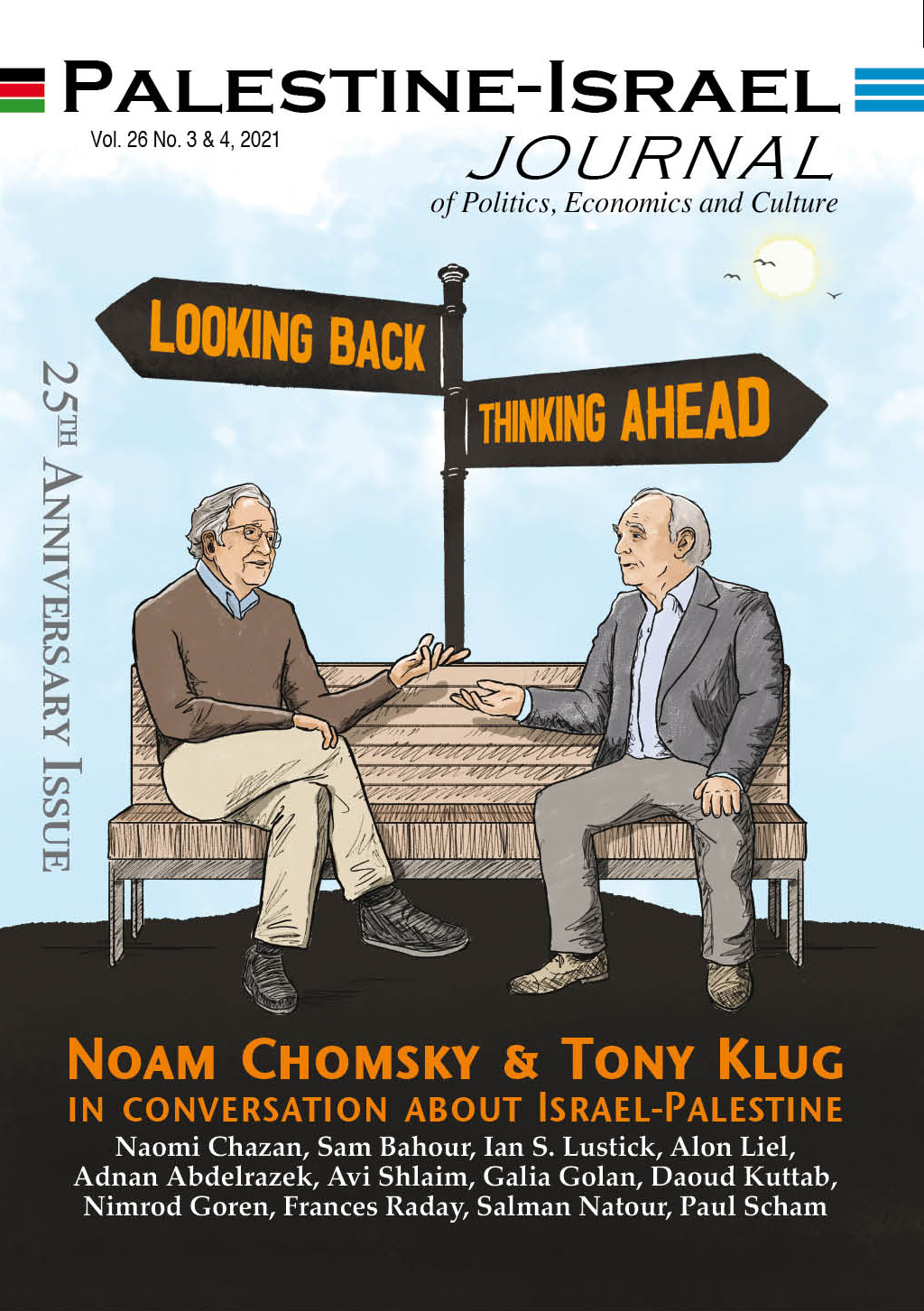

In his conversation with Tony Klug, Noam Chomsky argues, with citations, that no Israeli prime minister has agreed to the idea of a Palestinian state. I suspect, but cannot prove, that most Israeli prime ministers would have preferred autonomy rather than statehood for the Palestinians. However, I think it wise to first ask: What kind of state? The answer lies in the preferred plans for the Jordan Rift Valley. In fact, the Levi Eshkol government, in its post-Six-Day War discussions, was convinced that the Arabs would never make peace with Israel and that even if they did, they would not keep that peace. Therefore, in the government discussions of June 18 and 19, 1967 regarding the recommended positions to be presented by Israel at the United Nations, the idea of Palestinian statehood was in fact proposed. It would be a state in every way, with a foreign policy, for example. However, since in the same discussion it was agreed that Israel should hold onto the Jordan Rift Valley (for security reasons, since the Arabs would never fully accept Israel). Therefore, the proposed state would be “territorially surrounded by Israel.” This idea of statehood was even conveyed on behalf of the government to the major Palestinian families in Jerusalem, who rejected it.

Vision of Palestinian State Under Israeli Control

In subsequent proposals and even negotiations and for various reasons, the demand for an Israeli presence or control of the Jordan Rift Valley was repeated. Thus, Palestinian statehood was accepted in some cases, at least in principle, but limited by Israel’s control of the territory surrounding such a state or other parts of the West Bank. Additional demands were also made over the years, including, for example, Israeli control of the skies or the electromagnetic field or the maintenance of early warning stations in the West Bank – all demands made at one time or another that threatened to limit the Palestinians’ sovereignty of their state. The most recent proposal, the Trump plan, even called for Israeli approval for immigration to the Palestinian state, in addition to control of the Jordan Rift Valley, and multiple scattered areas between Israeli enclaves to be called a Palestinian state.

Only Ehud Olmert — the only prime minister to agree to the creation of a Palestinian state next to Israel — was willing to accept an international force to protect the Palestinian-Jordanian border, although Ehud Barak may have agreed to such a force as well at the Camp David talks of 2000.

Israeli Leaders Road to Acceptance

Returning to Chomsky’s claim, even though Barak did not speak approvingly of the creation of a Palestinian state, his positions at Camp David 2000 were all premised on the idea of a two-state solution, with the borders and other issues under negotiation. Even Rabin, as Klug asserts, was moving in that direction. While Rabin himself presented an autonomy plan in 1989 and in his oft quoted last speech, November 5, 1995, spoke of less than a state,1 his whole approach with regard to Oslo, especially Oslo II, was that Israel would withdraw, gradually, and increasing control would be turned over to the Palestinians. Pre-Oslo and for many years, Rabin insisted that he would not speak with the PLO because there was nothing to speak with them about, the implication being that the only thing the PLO would want to talk about was statehood. Yet approving the Oslo principles and the gradual transfer of power to the Palestinians strongly suggests that Rabin altered that opinion when he entered into talks with Arafat, however reluctantly. If borders were to be left for final-status agreements, obviously something like a state (borders of something) was to be on the agenda. This is not to say that Rabin was pleased with the idea; indeed, he did say something less than a state and he did seek an Israeli presence in the Jordan Rift Valley, but he did want to end the occupation. He was fearful that holding onto the territories would lead to a binational state. He himself proposed autonomy in 1989, but he also agreed, in Oslo II, to a gradual Israeli withdrawal and leaving the future of the settlements as well as borders and refugee issues to the final-status talks. In other words, whatever may have been Rabin’s personal preference, his approval of Oslo and especially Oslo II supports the conjecture that he knew and agreed to the topic he understood to be the ultimate agenda — the creation of a Palestinian state – the final parameters of which were left for the final-status talks.

Subsequent hawkish leaders, namely Olmert, Livni, and even Sharon, shared Rabin’s concerns. Yet all three, including Sharon, were wary of Israel’s remaining in the occupied territories. As Sharon put it to his faction at the Knesset, “...you may not like the word, but what is happening is an occupation - to hold 3.5 million Palestinians under occupation. I believe this is a terrible thing for Israel and for the Palestinians….”2 His speeches and interviews were full of warnings of the danger of a slippery slide to a binational state. And, of course, the matter of an Israeli presence if not control of the Jordan Rift Valley was essential, except to Olmert. Actually, Sharon was the first Israeli prime minister to accept the idea of a Palestinian state, albeit with territorial demands. Olmert may have been the only Israeli prime minister to fully accept the idea of a Palestinian state and an international presence on the Palestinian border with Jordan. Yet all the negotiations from Rabin through Olmert and Livni were premised on the idea of the two-state solution. All these prime ministers, and even Livni today, argued and I assume believed that all the territory belongs to the Jews, to us. Rabin reportedly said, and I have heard Livni say, it is ours, but we are willing to give up some of it (for peace). The question was always how much territory had to be relinquished. Barak’s government went to Camp David in July 2000 committed to reaching an agreement, which could only be based on two states. In fact, the 1999 Labor party platform included a Palestinian state. Like leaders before him, however, Barak’s territorial demands (retention of at least 8% of the West Bank) precluded PLO agreement, as concluded by Israeli intelligence even prior to Camp David.

Ignoring the Arab Peace Initiative

Regarding a positive response to the Arab Peace Initiative (API) adopted by the Arab League in 2002, it is indeed surprising, that the Israeli Government, even under Olmert, was not willing to consider the API. The altered formula on the refugee issue, written by Jordanian Foreign Minister Marwan Muasher (previously Jordan’s first ambassador to Israel following the 1994 peace agreement) along with the stipulations that agreement would bring an end to the conflict along with security and peace for all the states, should have been welcomed by Israel. There are reports that Olmert in fact was willing to give the API more attention.3

Yet, while Israeli leaders might have been able, or might still be able, to bring the public along, two things appear to be clear: Aside from Rabin, Olmert, and Sharon (perhaps Livni can be counted as part of this group), no Israeli prime minister was willing to give up the territories – the obvious but inevitable price for peace. Yet, Rabin, Olmert, and Sharon, all generally hawkish in their views, opposed indefinite occupation and believed that it would be necessary to end the rule over millions of Palestinians if their Zionist beliefs were to be secured.

The Challenge of Gaining Public Support

The other problem, which remains today, is the Israeli public. Opinion polls show a decline in public support for the two-state solution, yet support remains. Moreover, it is likely – though not subject to proof – that a leader who could present a peace agreement based on two states would garner public support. There would be spoilers, but recent studies have found that if the government of Israel decides, it will be accepted.4 Indeed, there are ways to cope with spoilers, even if their actions would be difficult to ignore.

Spoilers can be handled, but the real issue in connection with the Israeli public remains: How do we elect such a leader? The public ignores the occupation, willfully, and is not bothered by the continued conflict. Absent pressure from outside, from the European Union or the United States, it is hard to envisage a situation in which the public will press for an end to the conflict by electing a leader who will move in that direction. Palestinian violence might bring the occupation more into focus, but we know from experience, especially that of the second intifada, that violence tends to lead to the opposite public reaction, even more of a “rally round the flag” mentality than outside pressure might incur. In any case, and absent pressure of any kind, the government we elected most recently speaks of shrinking, containing, and reducing the conflict (https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/30/world/middleeast/israelbennett-palestinians-shrinking.html…. ), not ending it.

.jpg)

Peres Championed Dovish Positions

I’m not certain that Chomsky’s denial of Shimon Peres as a peacenik warrants refutation. As a member of the Labor party from 1977 to 1992, however, and also a member of the political committee tasked with writing the party’s platform, I had personal knowledge and much contact with party leaders. In the days following the 1977 election (and Mapai’s fall from power for the first time), Hug 77 was created. Composed mainly of university lecturers, i.e., dovish members or supporters of the party, Hug 77 was founded in my living room and was dedicated to a resolution of the conflict. We had no official link to any of the party leaders, but at the time Rabin was the leader of what was termed the “activist” or hawkish faction of the party originally headed by Yigal Allon, and we doves felt aligned with Peres. Broadly speaking, individuals such as Yossi Beilin, Chaim Herzog, and Haim Ramon were influential doves with whom we cooperated, especially on the political committee, in contrast and often opposition to Rabin, who was seeking permanent Israeli control over additional areas such as Gush Etzion and the northern shore of the Dead Sea. As an associate of Peres, I always found him a champion of the dovish position which, over time, included the two-state objective. Personally and as a leader of Peace Now, I never experienced the contrary nor had reason to doubt Peres’ position. This may not suffice as proof, and it did take time for the party officially to advocate the creation of a Palestinian state,5 but as the spiritual father of the Oslo process, Peres understood the likely outcome of the process, especially given its initiators, Beilin, Ron Pundak, and Yair Hirshfeld, all of whom had openly advocated for a two-state solution after the PLO adopted it in November 1988 (and Peace Now organized a major demonstration under the slogan of “speak peace with the PLO now.”)

Yet, despite all the progress that has been made in bringing the PLO to the two-state idea, the situation in Israel today does not provide much reason for optimism. Leaders on the left — Labor and Meretz and, of course, the Joint List — still support the two-state solution. However, the chances of any of these parties leading the government in the near future are remote, to say the least. Indeed, that is the problem. In the many elections of the past decade, the Israeli public has clearly rejected these parties. Instead, the public has repeatedly chosen center-right or right-wing parties, and now a coalition led by the religious Zionists. One may take some comfort in the fact that the Yemina party received only 6 mandates, but that does not change the fact that the Israeli public today has little to no interest in the occupation, the API, or the conflict at all.

Nothing Will Change Without Pressure for Change

There are, indeed, a plethora of peace organizations, and many of them can boast an influx of young people who have recently completed their military service. But these truly inspiring groups make up only a small fraction of the Israeli electorate. Moreover, the unwillingness of the coalition partners to see the coalition collapse has led to what appears to be a reluctance to raise the issue of peace negotiations. Similarly, repeated appeals to members and even leaders of the EU, and also the priorities of the Biden administration in the U.S., provide little reason to expect pressure from abroad to change the resistance of the present Israeli Government to negotiations, much less the compromises necessary for peace. It is, nonetheless, encouraging that Washington is still willing to oppose Israeli plans for more settlement construction, and this opposition can, and has, created enough pressure to at least delay such plans.

This is a familiar situation and, perhaps, the most we can hope for at present. Yet, lest I sound defeatist, we can be sure that nothing will change if we do not continue to press for change. Given the Israeli political system, this change will have to come from the political parties, and these must produce leaders willing to face – and end — the moral as well as other consequences of continued occupation. The political parties must be aware of potential support for such a leadership – and this is where our extraparliamentary activities come in. No change will come, neither in the form of pressure from outside nor through domestic elections, if there is not a sense that the Israeli public wants peace. There are many ways to bring this about and to demonstrate it. There are many publics here that must be addressed.

Under Ehud Olmert, a second-generation right-winger, we came quite close to an Israeli-Palestinian agreement. True, there are, and will be, spoilers, including Islamists such as Hamas. But there are, solutions to all the core issues, since the Clinton parameters of 2000 to the Annapolis process initiated by Olmert and Abu Mazen. The tragedy is that these solutions have been out there for a long time, and the adversary, the PLO, as well as the regional players, have all undergone change, even transformation over the past decades. It is time for Israel to undertake such a transformation.

____________________________

1 http://www.rabincenter.org.il/Items/01103/RabinAddressatapeacerally.pdf

2 The quote can be found on the Kadima website and in Galia Golan, Israeli Peacemaking since 1967: Factors behind the Breakthroughs and Failures, Routledge, 2014, p.169 and note 15. Sharon’s government accepted the Road Map proposed by the Quartet in 2004, which included the ultimate creation of a Palestinian state. Israel’s 14 reservations did not exclude this clause, stating only that the details of such a state were to be negotiated.

3 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/mar/30/israel2

4 Golan and Sher, Spoilers and Coping with Spoilers-Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations, Indiana University Press, 2019.

5 Oren, Neta, “Israeli identity formation and the Arab-Israeli conflict in election platforms, 1969-2006,” Journal of Peace Research, 47(2), 193-204.