In September 2020, the Abraham Accords, signed by Israel, the UAE, and Bahrain, were published — the first official peace agreements between Israel and an Arab country since the peace treaty with Jordan in 1994. Although the Abraham Accords were presented by the signatories as an important milestone toward regional cooperation, they do not address the continued occupation or the rights of Palestinians, leaving the most controversial issues aside. Coincidently or not, they also fail to mention women and, as such, do not differ from previous accords signed by Israel in the 1990s in their approach to gender in terms of process, content, or discourse.

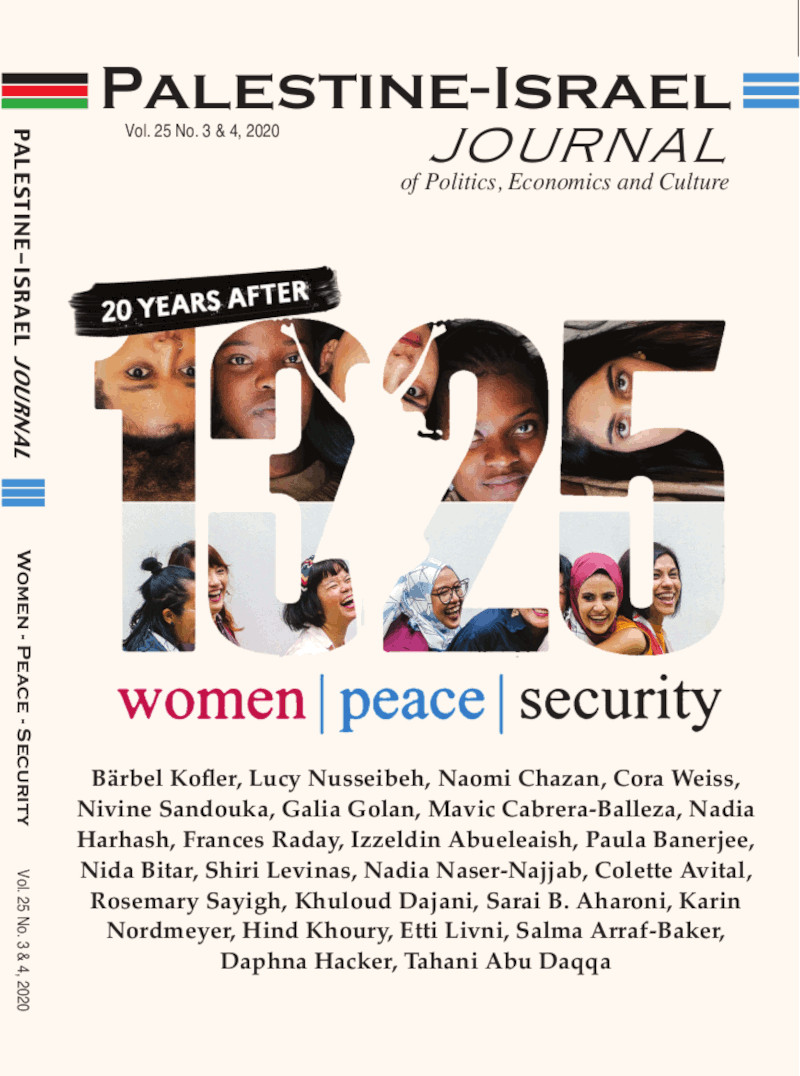

Given that 20 years have passed since the emergence of the United Nations’ women, peace, and security (WPS) agenda and that 10 Security Council resolutions have been adopted on related matters, this is worth examining in more detail. It is possible that the continued underrepresentation of Israeli women in diplomatic attempts to resolve political and military conflicts in the Middle East implies that the Security Council, as a normative actor, has failed to exert external pressure to promote cultural values concerning gender equality in one of the most conservative regions in the world.

Conservatism, in the context of the Middle East, is linked to deep cultural beliefs about the inability of women to perform high leadership roles and to societal norms that prohibit or limit their political participation. These values, I argue, are shared by Israelis and members of Arab countries or groups that engage in official negotiations in the region from time to time (Egypt, the PLO, Jordan, Syria, Hamas, Lebanon, and the Gulf states). Although this pattern may not appear as a linear trend, it is dominant and disturbing. Reckoning with this pattern is essential to move forward toward the full inclusion of women and other minority groups in future attempts to resolve regional conflicts, especially the question of Palestine.

The Abraham Accords: A Conservative Approach to Peace

A close reading of the Abraham Accords demonstrates the persistence of conservative approaches to peace. It reveals that the term “peace” is now connected with “human dignity and freedom, including religious freedom.” The emphasis on religion continues as the accords mention various forms of diplomatic and practical cooperation, such as “interfaith and intercultural dialogue … among the three Abrahamic religions.” Putting aside the references to technology and aviation, the choice of words is strikingly medieval in its conceptualization of cooperation, presented as “recognizing that the Arab and Jewish peoples are descendants of a common ancestor, Abraham, and inspired in this spirit to foster in the Middle East a reality in which Muslims, Jews, Christians…live in a spirit

of coexistence.” The carefully selected wording contains references to mutual recognition, stability, prosperity, sovereignty, and security. Those acquainted with regional history might find similarities to the Treaty of Jaffa (September 1192), which ended the 'Third Crusade' and determined a truce between Saladin and Richard the Lionheart by settling the status of Jerusalem and religious minorities. The total absence of contemporary political vocabulary is striking. The agreements do not mention, even once, the words “democracy,” “rights,” or “equality.” Given that the United States was the primary mediator of these accords, the absence is truly alarming.

As a longtime scholar and activist working on gender and formal Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations, I was far from surprised. Several structural characteristics which were already observed in previous diplomatic encounters in the region reappeared in 2020. These include: the dominance of male negotiators and mediators among all parties to the agreement; the secrecy surrounding the process of negotiations; the lack of transparency and media exposure; and the absence of civil society representatives or public consultations. What seems new is the heavy reliance on religious discourse to legitimize the agreements and position them within a set of “shared values” that apply to both Muslims in the Gulf region, Jewish Israelis, and Christian Americans.

The Shift from Security-Based to Faith-Based Peace Is Problematic

From a feminist perspective, this religious turn is highly problematic. Let’s remember that the call for women’s inclusion in politics has been joined by religious women (Jewish, Christian, and Muslim), who, since the 1970s, have offered feminist reflections and experiments with Godlanguage. These attempts have resulted in a detailed critique of traditional texts and images that portray God as man and with a call to adopt alternative religious imagery and practices. Nonetheless, the presentation of the “Abrahamic” traditions in the recent accords conveys them as an unchanging cultural heritage that is deeply linked with masculine political power. Indeed, most of the countries in the MENA region, including Israel, share similar discriminatory legal practices that are based on religious laws in matters of personal status and leadership roles. I suspect that, nowadays, the term “faith” appears as a key symbol, replacing the word “security” as a dominant frame. So, while militarism shaped the structure and language of the Oslo Accords, the Abraham Accords use a different, masculine sphere to exert legitimacy: religion and faith.

This shift deserves some attention. Historically speaking, Israeli women were rarely visible in previous rounds of official negotiations.

During the Oslo process, which was based on a secular-national logic of sovereignty and self-determination, this absence was related to the dominance of security issues and military personnel. To understand the erasure of women’s agency and the denial of public knowledge about their actual peace work, I conducted dozens of interviews in 2005-6 with Israeli women and men who participated in the official Oslo process (Aharoni 2011). Similar to other feminist scholars who tried to trace the ‘missing women’ in peace processes (Anderson 2016; McLeod 2019), this was an attempt to understand why, despite Israeli women’s growing education and participation in the workforce and in grassroots organizations at the time, they were not included in official peace negotiations. As I insisted on listening to these nonprotagonists, I found that women were designated as “specialists” — namely, mid-level negotiators, professional experts, and legal advisers — or performed supportive roles as spokeswomen and secretaries. As such, their invisibility was justified by their rank, and since women were almost never official signatories, their erasure from history became a fact.

Knesset Amendment on Status of Women Failed to Generate Reform

I learned that the denial of public recognition was a byproduct of institutional practices and cultural values. Resolution 1325 was meant to address both of these sources of bias. For example, WPS legal documents suggest that institutional practices of inclusion and exclusion could be amended by various mechanisms to ensure women’s full participation. Indeed, on July 20, 2005, the Knesset passed an amendment to the Women’s Equal Rights Act of 1951, mandating the representation of women on public committees and “national policymaking teams,” including “in any group appointed to peacebuilding negotiations.” The amendment was drafted in

order “to create public awareness of women’s roles in peace processes as defined in SCR 1325” (Committee for the Advancement of the Status of Women, 2004) and remains the first documented case of implementation through state legislation.

Aside from the failed Annapolis peace summit (the last serious negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians in 2007-8) which involved then-Israeli Minister of Foreign Affairs Tzipi Livni and then-U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, however, the amendment failed to generate any durable institutional reform. In fact, the appearance of these two women as protagonists in the Sisyphean struggle for peace in the Middle East has gone generally unnoticed by feminist scholars of international relations. This absence is perhaps both a byproduct and a signifier of the nonevent prototype paradox: from a mainstream perspective on Israel-Palestinian peace negotiations, Livni and Rice were too feminine to be taken seriously; from a feminist viewpoint, they might have been identified as mere symbolic tokens.

Israel Has No National Action Plan to Promote 1325

The lack of implementation of the Women’s Equal Rights Act was followed by the failure of the Israeli government to respond to the 2012- 14 “Civil Society Action Plan to Implement UNSCR 1325” (http://www.itach.org.il/wp-content/uploads/tochnit-peula-en.pdf). In 2020, the state of Israel still does not have a National Action Plan (NAP), and what is worse is that Israel has been lying to the international community about this. For example, in the recent Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) report, the Israeli Authority for the Advancement of Women used vague and ambiguous language, declaring that it “continues to enhance the implementation the UNSC Resolution, inter alia, through government Resolution No. 2331, which includes a full policy plan for the promotion of gender equality; the issuance of the Gender Mainstreaming Guide; an Interministerial Team for

National Action Plan, and more” (WAA 2017). These failed attempts might lead us to two conclusions: first, that Israeli men are actively preventing women from accessing formal decision-making on matters of security and foreign policy; second, that the international community does not have the appropriate institutional mechanisms to ensure member states’ compliance with soft international norms concerning gender equality in security matters.

How did this occur? The failure to produce strong institutional mechanisms for women’s participation reflects the complex ways in which asymmetry and power relations between men and women play out in peace politics. One institutional trait of Israeli peace diplomacy which I find important is the tendency toward secrecy. The recent Abraham Accords, like all previous ones, were drafted in a highly restricted process. I identify this as an exclusive “secret society” inclination. Conducted by a carefully selected, close-knit group of two to 15 people, such diplomatic encounters involve multiple actors who are not necessarily trained foreign service diplomats or elected legislators: political leaders, military personnel, civilian representatives, and others. Gender bias in these settings is so common that women’s involvement or absence may even go unnoticed. So, male-dominated political elites are able to create back-track forums to shift the locus of power from formal to informal mechanisms. And they leave women out.

Changing deep cultural beliefs about women’s inability to engage in international politics seems to be even more difficult to tackle than engaging in institutional reform. In a recent article, Noa Balf (2019) argues that the lingering status quo in Israel-Palestine poses a formidable challenge to democracy because it has resulted in a feminization and consequent discrediting of alternative policies toward peace. In this context, peace is perceived as a feminine trait and thus “a hypermasculine security state cements the Israeli security paradigm as infallible and permanent, and further disrupts the potential success of future negotiation efforts.” As I demonstrated earlier in this article, patriarchal values can morph and transform. I call this the “switching effect” — namely, that it could be that faith is now being used in the way security was once referred to — operating as a legitimizing discourse that excludes women and emasculates peace.

Exclusionary Practices Continue to Dominate Regional Politics

To conclude, structure and culture are both important for understanding the uneven process of change and stagnation in the attempt to implement 1325 in the Israeli context. What this case brings to mind is that while it is imperative to document the success stories of women’s participation in peace agreements, it is also necessary to learn about their erasure and failures. Israeli women were made invisible in the 1990s and, consequently, were barred from future diplomatic processes. The appearance of international norms and transnational movements that called for the inclusion of women in conflict resolution did not change this pattern, despite various attempts by women political leaders, local feminist organizations, and activists. Furthermore, exclusionary practices continue to dominate regional politics and may have even worsened due to the reemergence of conservative values and right-wing politics. Again, this reminds us that the struggle for a peaceful, democratic, and equal society in Israel/Palestine requires a profound change

in the mindset and language of all societies and communities in the region in order to ensure that everyone, including women, has a voice.

References

Aharoni, Sarai. 2011. "Gender and “Peace Work”: An Unofficial History of Israeli-Palestinian Peace Negotiations." Politics & Gender 7(3): 391-416.

Anderson, Miriam J. 2015. Windows of opportunity: How women seize peace negotiations for political change. Oxford University Press.

Balf, Noa. 2019. "The Status Quo and the Feminization of Political Alternatives: The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict." Israel Studies Review 34(1): 27-46.

Committee for the Advancement of the Status of Women. 2004. Session 131. The 16th Knesset, Jerusalem, November 09.

McLeod, Laura. 2019. "Investigating “Missing” Women: Gender, Ghosts, and the Bosnian Peace Process." International Studies Quarterly 63(3): 668-679.

WAA, June 15th, 2017 “Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention pursuant to the simplified reporting procedure”, Sixth Periodic Report to CEDAW, Israel.