As I write this in mid-March of 2020, events, priorities and attitudes are changing at a dizzying speed. Everything is eclipsed by fear and apprehension regarding the coronavirus. Even before the virus took front and center, the rapid reversal in the political fortunes of Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden as a result of the South Carolina primary on February 29 and Super Tuesday on March 3 meant that most Democrats (though by no means all) accepted that they would almost certainly be relying on Joe Biden to defeat Donald Trump in November, which is their overwhelming priority.

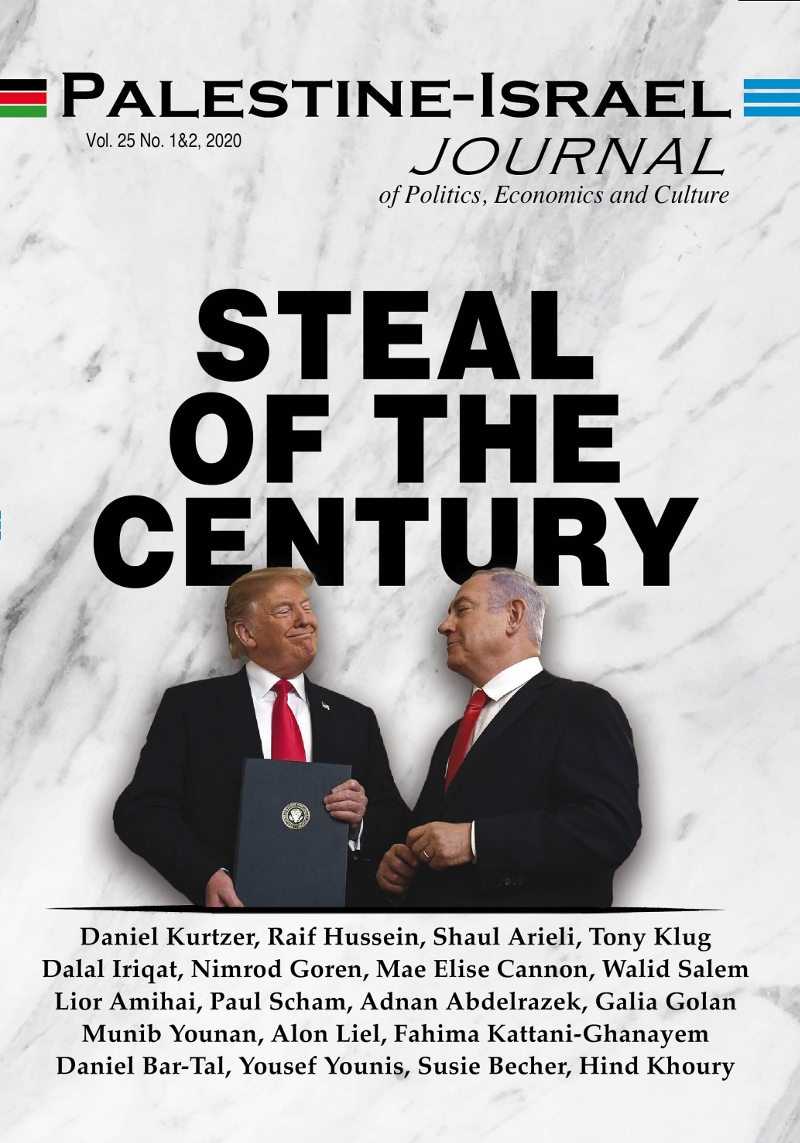

Under these circumstances, the “Deal of the Century” seems farther than ancient history; rather, it feels like it took place in another universe. The fact that another (apparently inconclusive) Israeli election was held on March 2 was barely a blip for most of those outside the comparatively small circle of dedicated and passionate Israel-watchers. Benny Gantz’s appointment to try to form a new Israeli government received only a brief mention in the news after the extensive coverage of the coronavirus crisis.

Democratic Differences

Obviously, the main determinant of a policy shift will be which party wins the election in November. Assuming for the moment that the world will have “normalized” by the time a new Democratic president is inaugurated on January 20, 2021, American politics will shift significantly with regard to Israel. However, though Biden appears to be the presumptive nominee, if he is elected, he will face a variety of attitudes inside his party that were previously largely marginalized. While Sanders has never taken the lead on issues regarding Israel, he has nevertheless been articulating what a substantial number of rank-and-file Democrats are feeling. These attitudes have already begun seeping into Congress, as witnessed in the “Squad,” composed of four freshman Democratic representatives. Some openly support BDS (Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions), and there is increasing discussion even among J Street supporters of possibly using threats to cut military aid as leverage to change Israeli settlement policy.

However, given the rapidly diminishing possibility of Sanders attaining the Democratic nomination, these currents are unlikely to seriously affect American policy in the near future. As discussed below, U.S. foreign policy is almost completely under the control of the president. Moreover, though the Sanders wing will presumably retain some influence in drafting the party’s platform, Sanders’ own interests primarily pertain to issues of economic inequality, and he is most likely to concentrate what firepower he retains in that area. In any case, platforms rarely constrain a president who has different ideas.

Changes on the Left

Until recently, there has been a continuum of opposition to Netanyahu’s policies and Trump’s embrace of them. It has stretched from mild (often private) opposition in Congress and the Democratic establishment, through the vocal “pro-Israel and pro-peace” J Street-oriented camp to the more radical IfNotNow, and then Jewish Voice for Peace — ending up with a fairly small (though growing) number of frankly anti-Zionist and pro-Palestinian Jews. The point of rupture is likely to be between the “Zionist left” (a name some are uncomfortable with) and those whose feelings about Israel as a Jewish state are, at best, ambivalent. In the last two years, 11 separate groups on the Zionist left have loosely affiliated in the new Progressive Israel Network, which includes J Street, Americans for Peace Now, the New Israel Fund, Partners for Progressive Israel, and seven more. Many within these organizations are sympathetic to Sanders’ calls for change and are toying with previously unacceptable strategies such as withholding some aid, but they wonder, on this issue and others, whether Sanders might go too far or might be unelectable — or both.

As of this moment, the momentum has switched abruptly from Sanders to Biden, largely on the issue of electability. Eighty percent of American Jews are anti-Trump and like many, probably most, Democrats, ousting Trump is their primary objective. Thus, Biden’s supportive attitudes toward Israel, in keeping with American policy since at least Jimmy Carter, might be less activist than they might prefer, but retiring Trump is the overriding priority for most of them.

This is in stark contrast to more radical and activist groups like IfNotNow, Jewish Voice for Peace and Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). The latter two support the BDS movement, while IfNotNow does not “take a unified stance on BDS, Zionism, or the question of statehood.” BDS has become the inflection point between the “radical” and “liberal” Jewish organizations. Sanders has repeatedly emphasized that he opposes BDS, but many of his supporters favor it.

Of course, opposition to Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s and Trump’s policies goes far beyond Jewish groups. Arab-American and Muslim groups have become more visible, evidenced by the election in 2018 of the first two female Muslim women to Congress. In addition, in the last few years, a genuine American radical left, disparate in specifics but identifying with the priorities of the international left, has become visible within the large “progressive” wing of the Democratic Party, which still supports Sanders’ candidacy and supported, though to a lesser degree, that of Elizabeth Warren. Among Sanders’ supporters and the “Bernie Bros,” there is a vocal minority that is openly supportive of Palestinians and opposed to Israel, not just the occupation. This movement, small as it is, is a new phenomenon in American electoral politics and is still largely confined to only a (growing) portion of grassroots Democratic activists.

Biden and AIPAC

Differences over Israel came to a head over the recent annual conference of the American-Israel Political Affairs Committee (AIPAC), held this year on March 1-3. Sanders, as well as Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg (still running at that point), chose not to appear at what has been an expected ritual of support, not only for presidential candidates in an election year, but also annually for senators and representatives. Biden, appearing via video, spent most of his speech praising Israel and the Obama-Biden record, not something likely to win points with most AIPAC supporters. He also strongly (if briefly) criticized both annexation and the recently announced plan to build 3,500 units in the E1 area, which would thwart any contiguous Palestinian state. His speech drew praise from Jeremy Ben-Ami, president of J Street. Biden, in common with all Democratic presidential candidates, has criticized Trump’s “Deal of the Century” and made clear he would not support it if elected.

Biden pleaded with AIPAC not to allow Israel to become a partisan issue between Democrats and Republicans, but that train has already left the station. Republican members of Congress either volubly support the “Deal of the Century” or keep silent about their criticism. Democrats seemingly universally oppose annexation and the “Deal of the Century” and actively support a two-state solution, though not the one outlined by Trump.

Activism in the Center

This campaign has also seen the emergence of a centrist group of establishment Democrats whose stated purpose is to maintain grassroots support for Israel in the Biden-Obama mold. The Democratic Majority for Israel was founded and is led by Mark Mellman, a veteran Democratic pollster, with the support of Israel’s traditional allies in Congress, including strong Israel supporters such as Representatives Elliott Engel, Nita Lowy, Steny Hoyer and many others. They vociferously support Biden over Sanders, who is their principal bête noir. If Biden wins, then their principles would likely guide his policy.

In practice, that might mean Obama-Kerry style attempts to encourage peace talks between the Israeli government and the PLO, a strategy now almost unanimously considered unworkable by most Israelis and most foreign analysts as well. Such a strategy might come into immediate conflict with the pro-annexation sentiment among Israeli Jews, most of whom welcomed Trump’s “permission” to annex settlements. A President Biden would undoubtedly revoke the “Deal of the Century” and withdraw support for annexation — meaning it would almost certainly be dead as U.S. policy — and probably forestall any Israeli attempts at it. This would mesh well with the nebulous centrism of Blue and White, which is pro-two state in theory but not so much in practice. It would also fit with Gantz’s enigmatic comment that he would pursue annexation in concert with the international community, which means no annexation, as the international community, apart from the U.S., is unanimously opposed.

A Future of Differences?

It is among the Democrats that support for Israel has become a genuinely contentious issue on a grassroots level, as mentioned above, and this has the potential to cause serious splits in the Democratic Party at some point, though probably not in this election cycle. Pro-Palestinian sentiment is active in a number of universities and within the growing progressive wing of the party. As noted, attitudes range from J Street’s “pro-Israel pro-peace” mantra to strong and open support for BDS. Arab Americans have been

vocally pro-Sanders in this campaign and, though their weight is nowhere near the volume of pro-Israel sentiment, they will certainly be an increasing element within the Democratic coalition. And if the Democrats increase their numbers in the House of Representatives in 2020, it is highly likely that the “Squad” will be augmented by new radical colleagues.

The Democratic establishment and most of its funders are solidly united against the upstarts, their own views ranging generally from liberal AIPAC attitudes to strongly held J Street-type opinions. Most Democratic presidential contenders appeared by video or in person at the last J Street Conference in October 2019. At this moment, however, Israel-Palestine is only dimly in the background, swamped as the current scene is by more immediate crises, especially coronavirus. This could change, especially if the Republican Party crumbles in the wake of a Trump defeat in November. New Democratic legislators who would pick up the pieces are much less likely to share Biden’s gradualist views and, as they advance in seniority, they could conceivably become the face of the Democratic Party within a decade or two.

Republican Rumblings

American foreign policy is made by the executive branch, and congressional input is in practice limited to control over spending. When it comes to a policy like the “Deal of the Century,” which involves little or no U.S. government outlays, there is almost nothing that even a House and Senate united against a president’s policy could do to stop it. Given that legislation can be vetoed by the president and requires a two-thirds majority of both Houses to override — as happened in February when he vetoed legislation limiting his power to order offensive strikes against Iran — that would be extremely unlikely to occur. Thus, were Trump to be re-elected and were he to continue to maintain the “Deal of the Century,” there is little that anyone could do to stop him.

It should be noted that many Republican legislators and funders have close ties with pro-settler groups, greatly strengthened since Trump’s appointment of David M. Friedman, his personal real estate (and bankruptcy) attorney, as ambassador to Israel in 2017. Friedman has been extremely active in support of settlements both before and during his ambassadorship. It is often unnoticed on the left that most settlers, though generally very enthusiastic about Trump and his policies, are dead set against the “Deal of the Century” because its end goal is, putatively, a Palestinian state, diminutive and shrunken as it would be. Thus, there might be opposition to the “Deal of the Century” on the American religious right, a strong force in the Republican Party, were any sort of Palestinian state to appear to be forthcoming. But the emergence of a Palestinian state under the “deal” is so hedged with conditions and restrictions, and has generated such universal opposition among Palestinians, that there is very little likelihood it would reach that stage. Republicans compete with each other to give the strongest support they can for Israel, but there is little policy discussion.

Conclusions

The “Deal of the Century,” though not completely stillborn, is unlikely to survive, let alone ripen into anything envisioned by its progenitors. This is beyond question if the Democrats win the presidency, though there is an absence of ideas for dealing with the issue, matching the absence of viable policy options on the Israeli left. Should Trump be re-elected, a prospect that seems less likely given the emerging understanding of his complete mishandling of the coronavirus crisis, and if the right retains power in Israel, still an open question at this writing, Israeli and U.S. leaders might craft a solution acceptable only to them and rejected by the rest of the world. Given the decline of American power and influence and, conceivably, the eventual re-emergence of a strong peace camp in Israel, the “Deal of the Century” is likely to be sunk with little trace that it ever existed.