Declaration of Independence, which states that the State of Israel will

In the late summer of 1993, like many Palestinians and Israelis who had been involved in efforts to bring an end to the conflict, I wholeheartedly shared the hope that accompanied the accord. But I never joined in the euphoria of many of my fellow travelers: Some of its key provisions left me — even at the time — deeply troubled and ill at ease. When I had the chance to carefully review the entire document on the eve of the Knesset vote 10 days after the historic signing on the White House lawn, it became clear to me not only that certain elements embodied in the text could prove exceedingly problematic but also that others — ignored or omitted — could be central to its success. Within months, these concerns gathered shape and form.

Ambiguity and Sense of Discomfort

The first, unquestionably, was the ambiguity of the aims. These focused on interim arrangements and a timetable for the completion of permanent settlement negotiations rather than on any concretely defined goal — notably, the creation of an independent Palestinian state alongside Israel (never mentioned explicitly in the document or clearly articulated by its drafters) and the termination of the Israeli occupation of the lands captured in 1967 (although references to United Nations Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338 are sprinkled throughout the text).

My sense of discomfort was compounded, secondly, by the prolonged five-year timeframe for negotiations. Aware of the multiplicity of issues (intangible as well as tangible) that could crop up during such a politically protracted and complicated period, even at that heady time I was hardly comforted by the assertion that this drawn-out process was essential to help accustom both sides to the changes that Oslo entailed. Indeed, this concern grew when I understood that the strategic conceptualization of this document, so preoccupied with elaborate interim arrangements, was faulty: It adopted an incremental approach which sought to build up gradually toward a comprehensive accord, in stark contrast to the Egyptian-Israeli treaty before it, which reached consensus on the details of the settlement and only then drew up a timetable for its implementation.

Third, inevitably, my ambivalence was reinforced when I realized that despite the elaboration of a variety of joint commissions, an extended list of economic and development priorities, a sensitivity to the importance of people-to-people connections, and a clear view of the West Bank and Gaza as a unified entity, the key substantive issues were being consciously deferred to a later stage. The importance of these questions is incontestable (borders, security, refugees, Jerusalem, settlements, and relations with other neighbors); several others, glaringly absent (reconciliation for one), are no less so. Much effort had been invested in form, very little in real content.

Fourth, even though the Oslo Accords presented a design which sought to include immediate neighbors (Egypt and Jordan) as well as other regional actors, they never explicitly defined their role or, for that matter, that of international actors. Norway had facilitated the discussions and the United States and Russia were signatories, but were they merely observers or were they also supposed to be guarantors or active mediators? Recognition of the importance of external involvement in what was essentially a bilateral process wasn’t translated into a more precise understanding of its scope or nature.

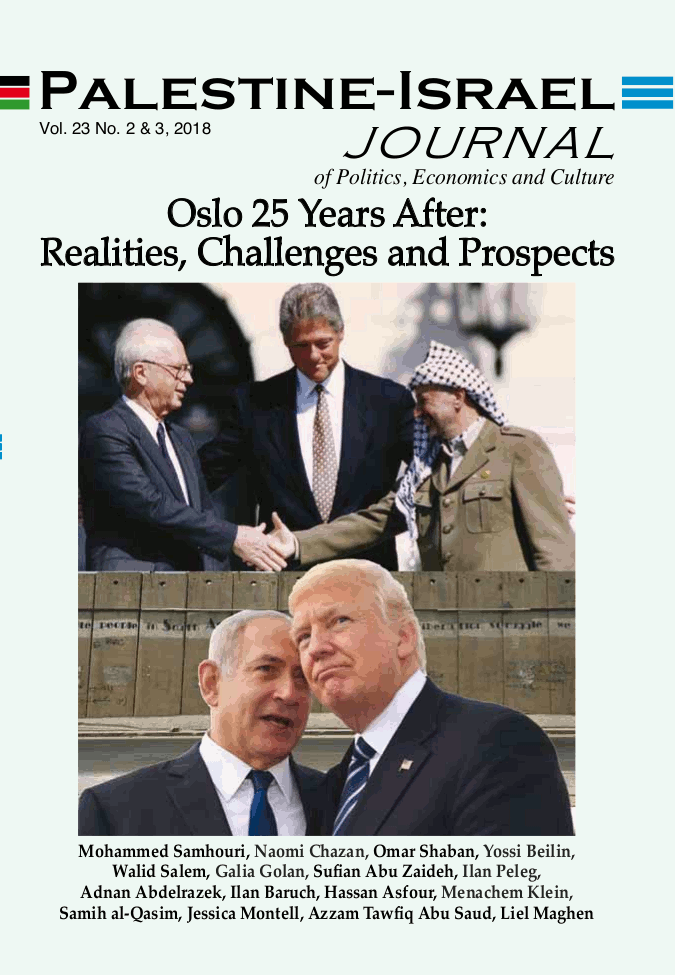

From the outset, then, the DOP, in my mind, was more a plan for negotiations than a detailed guide to their success. It depended heavily on the commitment and political gravitas of two very different leaders: Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat. These men, however distrustful of each other, were heavily committed to the process, enabling them to venture forth along with their supporters on what was then (as it is now) an extraordinarily precarious, yet increasingly essential, path.

Throughout the 1990s, I followed with growing trepidation how the dissonance between the promise embedded in Oslo and the obstacles it contained led to increasingly contested outcomes. Not only did each interim stage drag out longer than anticipated but, after the Gaza-Jericho Agreement of May 1994 (which led to the return of Arafat and the PLO leadership to the area), opponents on both sides began to organize and gain traction (especially right-wing groups and recalcitrant settlers on one hand, and militant — ideological and religious — Palestinian groups on the other).

Under these circumstances, the scope of subsequent agreements perceptively narrowed. This was apparent in the elaborate “Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip” (generally known as Oslo II) of September 1995, which divided the occupied territories into three areas, with full civil and security oversight of the newly formed Palestinian Authority limited to the major cities (euphemistically dubbed Area A), restricted to civil matters only in Area B (which pertained to 70% of the Palestinian population), and totally absent in 60% of the territory (Area C). Not only was the devolution of power to the Palestinians decidedly partial; it created a structurally and administratively truncated maze.

The Rabin Assassination Watershed

The assassination of Yitzhak Rabin on November 4, 1995, just after the adoption of the interim agreements, proved in retrospect to be a watershed.

Traumatized by the event, Israelis went to the polls only to usher Binyamin Netanyahu, the most vocal opponent of Oslo, into the prime minister’s office. Under his aegis, further agreements (the Protocol Concerning the Redeployment in Hebron of 1997 and the Wye River Memorandum of 1998) were reluctantly signed. These served to accentuate the innate asymmetry between the signatories and to solidify the fragmentation of the Palestinian territories without making any progress toward the permanent settlement. What could have been a process leading to an open peace with extensive interaction rapidly morphed into a closed, separate, divisive, violent, and unequal reality on the ground.

By the time Ehud Barak replaced Netanyahu in the 1999 elections, the mood in Israel had shifted perceptibly: The hope of the early days of Oslo was replaced by growing skepticism (if not downright rejection). A similar swing took place on the Palestinian side, as the exigencies of daily life replaced the promise of sovereignty.

When the ill-fated Camp David summit convened in the summer of 2000, the Oslo process was all but dead. It was finally put to rest when Ehud Barak insisted on a hastily arranged meeting based on jettisoning the stepby- step approach in favor of one that focused on reaching closure through the achievement of a comprehensive agreement. But Barak lacked both the substantive gumption and the parliamentary support needed to cement such a deal. His Palestinian counterpart, Arafat, was suspicious not only of his haste but also of his motives and capacities. After two fruitless weeks in July, during which working groups toiled while the principals barely exchanged a word, its participants dispersed amid mutual recriminations (the most vocal and damaging being the Israeli charge that “there is no partner on the Palestinian side”).

The following six months witnessed the outbreak of the second intifada as well as the breakdown of the far more interesting and detailed Taba talks based on the “Clinton Parameters” (promulgated on the eve of his departure from the White House), which took place in the midst of the Israeli special elections that brought Ariel Sharon to power. By then, the fate of the original Oslo trajectory had been sealed.

At this juncture, those of us in the Israeli peace camp were forced to deal not only with the abject failure of the Oslo experiment but also with the decline in political power that it entailed. There followed a new phase (2001-09), devoted entirely to a variety of attempts to revive Israeli- Palestinian talks. None of these were joint Palestinian-Israeli initiatives; these were relegated to track-two efforts (most significantly, the Geneva Accord of 2003, which spelled out the specifics of a full-fledged permanent two-state agreement) that did not obligate official echelons.

External Actors Take the Lead

While the leaders on both sides were at loggerheads and proponents of peace were shunted to the sidelines, the burden of jumpstarting negotiations shifted mostly to external actors. Each of the ensuing efforts, in its own way, sought to address some weakness inherent in Oslo. Intriguingly, what has proved to be the most enduring and significant, the Arab Peace Initiative (first adopted in March 2002), which sought to cast the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a regional mold and provide a broader solution, was barely noted at the time. The Roadmap for Peace, drafted by the Quartet and set in motion in April 2003, defined the aim of negotiations as a Palestinian state within a stepped-up, performance-based framework but petered out before it ever really got off the ground.

As violence grew and settlement activity proceeded apace, Ariel Sharon decided to take things into his own hands (partly as a means of thwarting his Roadmap commitments). In an exchange of letters with President George W. Bush in April 2004, he presented a plan for a unilateral withdrawal from Gaza (receiving, in return, implicit recognition of the large settlement blocs in the West Bank). This move gained support in the Israeli public but was heavily contested in Sharon’s coalition in general and in his Likud party in particular. The Disengagement Plan passed in the Knesset — substantially due to the votes of the opposition.

Although no longer in a position to directly influence the vote, I differed strongly with my colleagues who, I thought, in their haste to begin the process of ending (part of) the occupation, were actually giving a hand to its entrenchment. One-sided steps without the judicious transfer of power had proved a disaster elsewhere; there was no reason to believe that the chaotic results would be any different in this case. Moreover, there was something tremendously condescending in the exclusion of Palestinian representatives from this action — as if Israel had not only the capacity but also the right to decide their fate without any consultation. The implementation of the Disengagement Plan in the summer of 1995 has left its mark within the Israeli polity; it has also had untold repercussions for the inhabitants of Gaza and for Palestinian statehood. Its human cost and political damage continue to serve as a warning to those who still periodically advocate for unilateral measures as a substitute for negotiations.

By 2007, when Ehud Olmert and Mahmoud Abbas reaffirmed their commitment to the Roadmap in Annapolis, very little progress had been made on the negotiation front. In practice, however, occupation and settlement expansion continued apace, while their daily effects on Palestinian lives proliferated. The resumption of direct talks — involving, according to the Israeli prime minister, the most far-reaching concessions ever offered by an Israeli leader — never gelled into a full-fledged agreement. President Abbas’s reluctance to sign an agreement without studying a detailed map was compounded by Olmert’s abrupt resignation in the midst of corruption probes, the Gaza war of 2008-2009, and yet another round of Israeli elections which led Netanyahu to the premiership for the second time in early 2009. By then, although it was clearer to many what simply does not work, fewer prospects remained for future progress.

The Return of Netanyahu: From Conflict Management to Unabashed Control

A new phase followed, commencing with Netanyahu’s resumption of office in 2009 and spanning his next two terms, until the spring of 2015. This was a period marked by the purposeful entrenchment of the status quo, effectively erasing what was left of the substance of the Oslo Accords. The policy of conflict management was designed to shun any serious negotiations, Netanyahu’s proclamation of support for a streamlined two-state solution at Bar-Ilan University immediately after his political comeback notwithstanding. Under these circumstances, the intensive efforts invested by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry to revitalize negotiations during Obama’s second term fell victim to the vagaries of the regional turmoil attendant upon the Arab Spring, increased domestic pressure from diehards on both sides, and the dwindling influence of the vestiges of the peace camp (a repeat of the pattern that emerged during the George W. Bush administration). Although international pressure has continued (Paris 2017, for one), its influence has been meager.

The fallacies of nurturing a (nonexistent) status quo, however, escaped neither Netanyahu nor his Palestinian counterparts. Since his re-election for a fourth term in 2015, Netanyahu has replaced the notion of conflict management with one of unabashed control, ushering in the current phase of relations with the Palestinians, with Israel in practice expediting the gradual annexation of large segments of the West Bank while further relinquishing the last vestiges of its responsibility for its inhabitants. In what is nothing short of a systematic and subtle turnabout, he has orchestrated — with both the passive and active backing of the Trump administration — a paradigmatic shift from the management of the occupation (a term which he has worked hard to delegitimize) to creeping annexation and from settlement expansion to the institutionalization of separation and inequality between Palestinians and Israelis. This has further denigrated the lives of the Palestinians, heightened their despondency, and deepened their fragmentation. The Oslo trajectory — partly misconceived, inadequately implemented, substantially distorted over time, undeniably mishandled, and heavily manipulated — has come to an ignominious end.

Israeli and Palestinian societies have been almost unrecognizably altered since the heady days of September 1993. Internal schisms on both sides abound, religious extremism is on the rise, and democratic forces and values are in retreat. The political environment is especially fluid, with both Abbas and Netanyahu flailing (albeit for very different reasons). The level of mutual acrimony has risen to new heights as human contact has dwindled to a trickle. Mutual fear replaces the promise of reconciliation, and only a handful of diehards still believe that true peace is attainable in the domestic, regional, and international environments that are far less amicable to reciprocal understanding today than they were 25 years ago.

Only a Negotiated Solution Can End the Conflict: We Can Make It Happen

Just as I staunchly backed the Oslo Accords in 1993 but was not party to the elation of its proponents then, I do not partake in the gloom that has permeated the much-diminished peace camp today. We all have a share in failing to prevent the Oslo slippage in real time; we all bear responsibility for the banalization of peace and the consequent immiseration of the Palestinian people and the dehumanization of large swaths of Israeli society. That is why we have a special obligation to revive the vision embedded in the Oslo Accords and, by learning from the mistakes that led to their demise, reframe the path to their realization.

Only a negotiated peace can bring an end to the conflict. All the other options (such as unilateral action or prolonged violent resistance) surely do not facilitate mutuality, nor do they supply the minimal requirements for a just and lasting outcome. As many of the provisions of the Oslo process have lost their relevance and their feasibility has justifiably been questioned, it is high time we constructed a vastly revamped vision and architecture upon the more resilient conceptual, substantive, and procedural building blocks carefully devised and tested in the course of the multiple efforts to translate the prospect of a durable arrangement into a working and viable reality.

Recasting the steps toward a resolution of the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians must begin with updating and specifying a common goal; it can ignore neither their distinct historical narratives nor their ultimate need to create a common destiny. However more complicated today, any agreement must simultaneously respect the self-determination of the other while transparently embracing an open democratic vision involving substantial reciprocity. I am convinced that it is within our capacity, given the impossible alternatives, to concretize such a vision.

It is also within our power to make it happen. The internationalization of the process can prop up the substantive regionalization of the solution without detracting from the centrality of the role of Palestinians and Israelis on a variety of levels. But what is needed more than ever before is the daring to believe that it is possible and the good judgment to move forward. If we don’t, we will become the victims of the tragedy that we have allowed to unfold since the promulgation of the Oslo Accords a quarter of a century ago.