A popular anecdote tells of an Israeli traveler who, on arriving at a foreign port, responds to the questions on his visa form: “Sex — yes, please; Occupation — no, just tourism.” It is a joke, of course, and quite funny. But at its core it’s very unfunny, even tragic. Around the world, mention “Israel” and word-association instantly invokes “occupation.” But mention “occupation” in Israel, and almost no one knows what you’re talking about. It’s cognitive dissonance on a national scale. How can you end something that doesn’t exist?

Occupations are meant to be temporary affairs, whereby the occupying power is effectively a custodian of the occupied territory until its final disposition is determined. When the occupation of the West Bank commenced in June 1967, almost no one seriously imagined it would still be extant half a century later. The debate within Israel from the beginning centered around how much of the territory to return to Arab rule, and under what conditions.

With the recent breakdown of even the semblance of a “peace process,” the question today is whether the occupation will ever end, or if the future will be one of “permanent occupation,” an oxymoron if ever there was one. The status quo would be problematic enough if it were static. But its dynamic character — in particular the ongoing radical changes in the demographic composition of the West Bank — is confounding the prospects for an eventual resolution of the conflict and spreading despair among the occupied Palestinians, world leaders and many Israelis.

Adding to the despair is the anxiety that, in these times, the likely alternative to an indefinite occupation would appear to be annexation of all or part of the West Bank, an action that would not only be completely illegal under international law but would be politically explosive. It was for these reasons that the Israeli defense minister and war hero, General Moshe Dayan, reportedly retracted a proposal shortly after the 1967 war to extend Israeli law to the Occupied Territories. He was advised that such a move violated the Geneva Conventions — adopted by governments around the world in 1949 in the wake of the horrors of World War II — and would require formally annexing the territories and offering citizenship to its inhabitants.

Toying with the Fourth Geneva Convention

One of the principal provisions of the Fourth Convention, which regulates occupations, is that the penal laws of the occupied territory should remain in force. Israel accepted that Jordanian law would continue to apply (excluding the death penalty, which Israel had effectively abolished in its own courts).

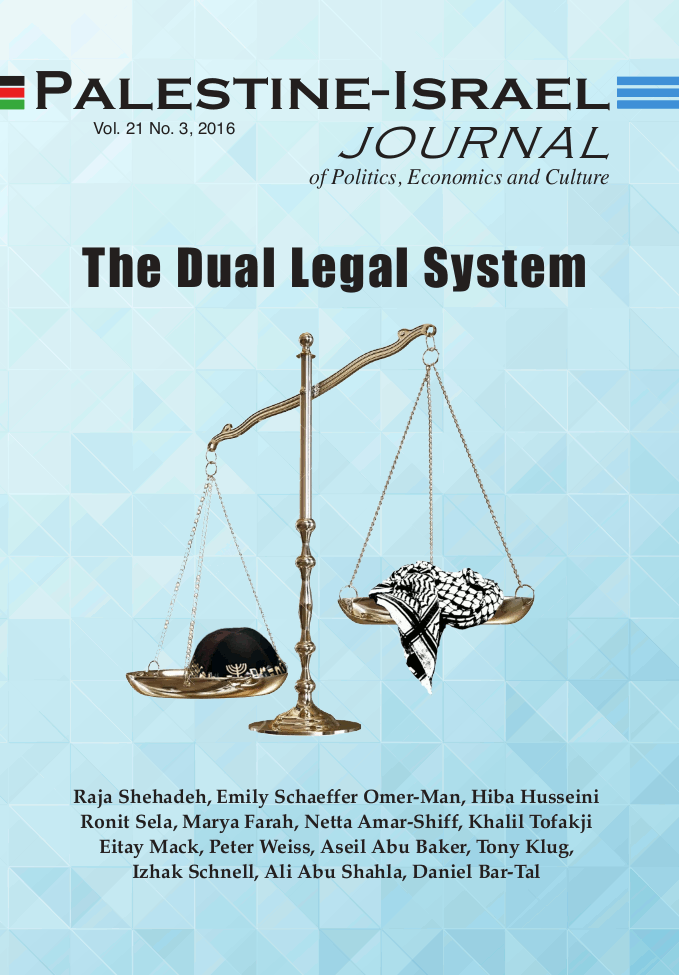

However, a permitted exception to this provision on security grounds — provided the measures introduced did not abrogate the Convention’s other provisions — gave rise to a parallel legal system in the West Bank. In August 1968, the Israeli military court in Nablus (one of five in the West Bank) ruled that two legal systems operated in the territory, and that Israeli military law — concerned with defense and security — was not to be guided by Jordanian law, the jurisdiction of which was confined to civilian matters. In practice, military law was often to take precedence by designating the alleged offence a security matter.

In a note to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) dated June 16, 1968, Israel “confirmed its desire that the ICRC should continue its humanitarian activities in the three occupied territories on an ad hoc basis and stated its readiness to grant to it all facilities required. But it … wished to leave the question of the application of the Fourth Convention in the occupied territories open for the moment” — a moment that has yet to expire. While Israel thus did not accept the applicability of the Fourth Convention, its government nonetheless maintained that it operated a de facto observation of the humanitarian laws above and beyond those required. This stance has enabled the Israeli authorities to pick and choose which clauses of the Convention to observe and which to flout.

Accordingly, it has disregarded the provisions that forbid annexing and settling parts of the captured territory but simultaneously invoked the laws of occupation that prohibit altering the legal status of an occupied territory’s inhabitants — to justify treating them differently from Israeli citizens (whether resident in Israel or the West Bank).

From the beginning, Israel held that the Fourth Convention related only to the sovereign territory of a High Contracting Party, and that neither Jordan nor Egypt was the legal sovereign in the West Bank or Gaza Strip when they had, respectively, governed these territories. In Jordan’s case, its formal annexation of the West Bank in 1950 — defying the 1947 UN partition vote which allocated the area to the Palestinian Arabs — was rejected by the entire international community apart from Pakistan and the United Kingdom. Egypt had held Gaza under military rule and never claimed sovereignty over it.

This technical argument, even if judged to have a degree of merit, was plainly more camouflage than reason. The real grounds were quintessentially political. If the government wanted to argue the opposite case, it would have found plenty of legal validation for that too.

Israel’s justification did not sit easily with its acceptance that Jordanian law would remain in force following the conclusion of the 1967 war, with its resolve to discuss the future of the West Bank only with Jordan, and with the part Israel played in facilitating Jordanian rule over the territory following the war of 1948. Moreover, Israel did not apply the Fourth Convention in its entirety to the captured Syrian Heights or the Egyptian Sinai Desert, even though there was no ambiguity about the legal status of these territories prior to the 1967 war. But Israel was sensitive at first to criticism, so that when alleged violations of the Convention were publicized in specific cases, Israel’s spokespeople often went to lengths to argue that their actions were not in breach of its provisions.

Israel was not unique in its cynical attitude towards international law. Governments that pay lip service to it when it suits them often look for ways of getting around it when it appears to clash with their own perceived interests. Jordan, Egypt, Syria and Lebanon, along with Israel, were all sent notes on April 4, 1968 by the ICRC, requesting each of them to abide by the Fourth Geneva Convention — which applies to any armed conflict, not just to occupations — and designate a Protecting Power or substitute, as provided for under the Convention. In its 1970 International Review, the ICRC recorded: “The only official reaction to this note was from the Jordanian government, which … limited itself to stating that it did not accept the ICRC’s viewpoint …”.

Israel’s efforts to quell unrest

Israel’s immediate challenge on inheriting the West Bank was to quell any insurgency and restore order. Secondly, it had designs on chunks of the territory, including but not limited to East Jerusalem, which it promptly annexed along with an extensive hinterland. Thirdly, according to the “coordinator of the administered territories,” Brigadier-General Shlomo Gazit, in an interview with the author in 1973, Israel sought to procure a permanent change in Arab attitudes toward the Jewish state and create a climate of goodwill. All three objectives, it was argued, would have been impeded by the Geneva Convention.

Gazit stressed that the occupation should be considered temporary and that, in the meantime, security conditions permitting, Israel should maintain a light presence in the territory. Indeed, in normal circumstances during the 1970s, a traveler could cross the lengths and breadths of the West Bank and only rarely come across physical evidence of military occupation (yet the occupation was firmly entrenched).

From July 1971, other than during periods of temporary curfew, West Bankers were more or less free to travel throughout Israel, too. I used to drive back and forth across the barely monitored border almost daily, sometimes with Palestinian or Israeli colleagues or both. There were no segregated highways, few visible Israeli settlements, and no genius had yet thought to divide the minuscule West Bank into three separate zones with different governances for each of them. Nor had unsightly eight-meter-high concrete walls and other barriers yet become a feature of the spectacular landscape.

As noted, military law per se did not infringe the Geneva Convention, and in some trials before military courts common-law rules were observed and acquittals were not uncommon. However, another wing of Israeli military law took its authority from the Defense (Emergency) Regulations of 1945, which did not pretend to follow the system of common law or apply the rules of natural justice.

These regulations had originally been introduced by the British mandatory regime and were directed primarily against the Jewish Underground. They sanctioned draconian measures, such as the demolition of houses that (knowingly or otherwise) had sheltered saboteurs, deportation of individuals, imposition of curfews and other collective punishments. The regulations also permitted administrative detention, under which a suspect deemed to be a threat to public safety or order could, in effect, through successive extensions, be detained indefinitely following a perfunctory hearing before a military court.

Other than preventive detention, these measures were in breach of the Fourth Convention. But Israel’s principal justification was, simply, that they were effective in quelling the mounting unrest that followed the inception of occupation. At first sight, the official figures appeared to bear this out, showing a steady rise in the number of fedayeen actions in the Occupied Territories from 1967 through 1969-70, but with few recorded instances in 1971-73. As these actions declined, Israel felt able to reduce the number of administrative detainees, deportees and house demolitions.

The key factor in reducing violence was hope

But to what extent was the drop in armed confrontations actually due to Israel’s harsh security measures? In 2005, an Israeli army commission found no proof of effective deterrence of house demolitions. Some commentators attributed the primary responsibility to “Black September,” in which thousands of Palestinian fighters were killed in September 1970 by the Jordanian armed forces. However, the flaw in this theory was that, for the West Bank alone, the peak year for incidents was 1969 — twice the number recorded for 1970. So it seems the reduction had set in well before Black September.

Curiously, a more critical role may have been played by the less lethal phenomenon of market forces. Unemployment in the West Bank immediately following the 1967 war soared to 30%. The initial Israeli government policy to combat this problem was to achieve economic selfsufficiency for the territory. However, this strategy was soon derailed by the sheer pull of an Israeli job market suffering a post-war labor shortage. By the end of 1971, unemployment among West Bank inhabitants had virtually been eliminated through employment in Israel, and economic prosperity rose to levels beyond pre-1967 imaginings. At least for a while, these developments dampened Palestinian enthusiasm to disrupt the evolving status quo.

But arguably the most decisive factor of all was the impact on the Palestinian psyche of the unexpected Arab defeat of June 1967. For many Palestinians, the trauma was particularly profound for it brusquely terminated a nineteen-year belief that the disaster of the 1948 Nakba was temporary and that they would soon be returning to their former homes and villages. Once the early shock of the outcome of the 1967 war diminished and the Palestinians started to come to terms with their new circumstances — including the reality of Israeli rule and of the Israeli state itself — they intuitively began to reappraise what the future might hold.

By the early 1970s, undercurrents of a shift in sentiment were already detectable whereby progressively more Palestinians were prepared to conceive a future Palestinian state co-existing alongside Israel, rather than in place of Israel. This emerging paradigm eventually surfaced as official Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) policy in 1988 and, five years later, the PLO openly recognized Israel under the Oslo Accords.

Although not everyone felt the same way, many West Bank Palestinians told me in 1973 that, after the anticipated massacres following the 1967 war did not materialize and the initial shell-shock started to fade, they tended to look at their enforced separation from Jordan as a potential emancipation, in that it revived the future prospect of Palestinian independence. The world, they felt, did not regard Jordanian rule as an oppressive alien occupation, as Jordanians were fellow Arabs and fellow Muslims. But these cloaks were absent in Israel’s case, and the international community, they confidently held, would not tolerate indefinite Israeli occupation! So they could now look to the future with greater hope for self-determination and statehood.

It was arguably these deeper processes, more than any security measures or military actions that accounted for the relatively peaceful period in the early years (post-1969) of the occupation. Whenever hope was stifled in later years, unrest or violence would break out again. On their own, security measures could never do more than, at best, contain the disturbances temporarily. The key factor was invariably the restoration of a political horizon.

Growing Illusions on Both Sides

Many years later, following extensive changes on the ground, the pragmatic view among both Palestinians and Israelis is no longer wedded to two states alongside each other. Ominously, there is a common growing illusion that a deal based on reciprocal recognition is no longer necessary. Indeed, there are indications that both sides are reverting to the ingrained attitudes of an earlier era when each summarily rejected the national imperative of the other.

On the Israeli side, there appears to be a growing perception of the Palestinians as weak and divided and — against a backdrop of nearly half a century of Israel ruling the West Bank —- a sharpening attitude that the Palestinians will have to accept their fate as a defeated people. The Palestinians, on their side, have witnessed a dramatic, if sometimes overstated, shift of international sympathy from the Israeli side to the Palestinian cause. This has fueled the belief among some Palestinians that they don’t, after all, need to come to terms with the Israeli reality, as time will take care of the problem in their favor. Thus, they too are slackening their allegiance to the notion of mutual national acceptance and reverting to their former maximal demands.

Sooner or later, Israel will have to face its moment of truth: Is it or is it not an occupation? If it maintains that its rule in the West Bank is not an occupation, Israel denies itself the only solid defense it has against the intensifying charge of apartheid. If it accepts it is an occupation, then it is way beyond time to bring it to an end. Sheltering behind a fictional peace process, after 20 years of hollow talks, is no longer a credible option even for the most resolute devotees of direct negotiations.

Equal national or equal civil rights

In principle, an alternative to withdrawal from the West Bank could be the provisional granting of equal rights to everyone living under Israeli jurisdiction. The indefinite denial of both national and individual equality flouts proudly trumpeted Jewish values and contradicts the essence of Israel’s Declaration of Independence. Yet it is doubtful that the individualrights option, particularly if it includes voting rights, will have much appeal in today’s Israel, for it would be regarded as an existential threat to the Jewish state. Conscious of the turbulence of Jewish history, the Jews of Israel are unlikely to jump at the prospect of becoming a minority again in someone else’s land.

On the face of it, such a move would also contravene the Fourth Convention, as it would entail altering the political and legal status of inhabitants of an occupied territory. However, objections from other parties, if at all, are likely to be restrained, provided it was made clear that this was not a unilateral imposition of one state but an interim arrangement pending a final agreed resolution. A comparison could be made with Scotland whose people might in future vote for independence but, until such a time, they are entitled to enjoy the same rights as all other inhabitants of the UK. For Israelis and Palestinians, as long as both peoples remain committed to having their own state, the eventual, mutually acceptable, outcome would logically have to be a version of two states.

If the Israeli government declines to make any move along the lines discussed here, other governments might be stirred to seize the initiative. One looming option is to admit Palestine to the United Nations as a full member state. In that eventuality, Israel, with its military bases in the West Bank, would find itself in daily violation of the sovereign territory of an independent UN member-state. In many respects, Israel’s legal position, to say nothing of its political position, would be a nightmare. Its moral standing might also be called further into question, even in the eyes of people generally sympathetic to its predicament.

So many promising opportunities have been spurned over the decades that it is increasingly hard to know what may now be done. But the key must be to induce new political currents in Israel to bring to power a government that is genuinely committed to doing a reasonable deal with its Palestinian neighbors and the wider Arab world.

The Palestinian-American thinker and business consultant Sam Bahour and I have proposed that the international community — individually or collectively — should give notice to the Israeli government that the time for cherry-picking the Geneva Convention is over and that it must decide by a given deadline (we have proposed the 50th anniversary of the occupation in June 2017) either to end the occupation and recognize Palestine or, alternatively, grant equal rights to Palestinians until the longer-term future is determined (http://mondediplo.com/blogs/if-kerry-fails-what-then). Removing international tolerance of the status quo as the automatic default option is critical. The aim, if equal civil rights is ruled out even temporarily, would be to shift the focus in Israel decisively back to the two-state formula.

Firm and imaginative initiatives are urgently needed from both Palestinian and Israeli civil societies. Separate but parallel campaigns to encourage the international community to demand of the Israeli government that it must choose forthwith between equal national or equal civil rights could help to reinvigorate the peace camps and restore a sense of future to both peoples before the remnants of hope are irreversibly extinguished.