In the first week of March 2016 alone, 64 Palestinians were left homeless by Israeli demolitions in the West Bank.1 According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the month of February 2016 saw the highest number of demolitions in the West Bank since it began documenting them in 2009, with 235 homes and structures destroyed, dismantled or confiscated.2 This resulted in the displacement of 331 individuals, including 174 children in February.

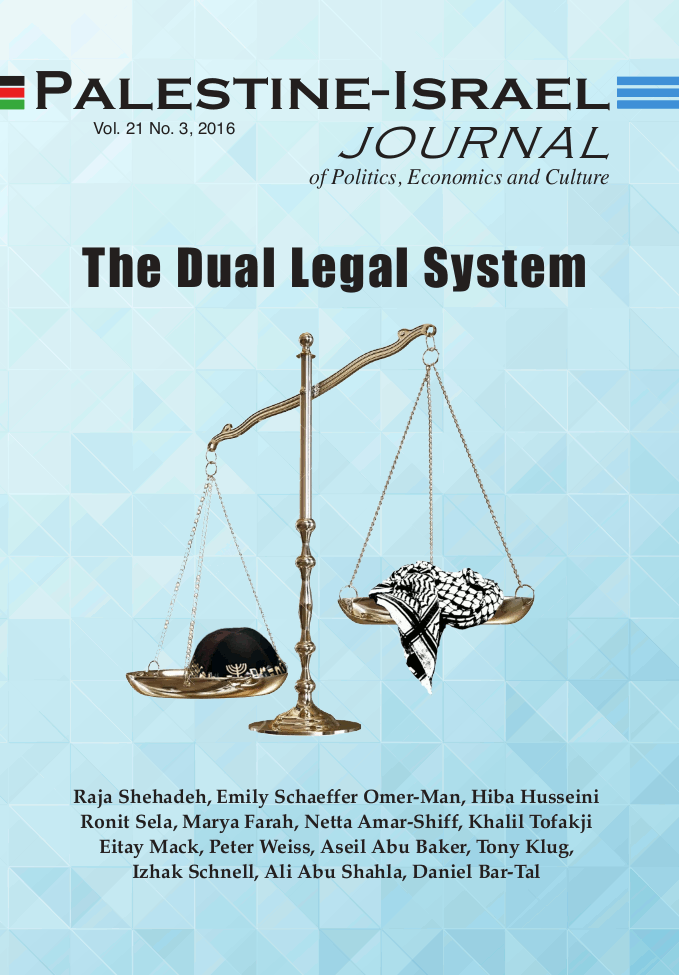

Communities targeted for demolition are often some of the most vulnerable, thus creating even more dire living conditions for individuals. In contrast to the visibly dismal and harsh human rights situation is the very sterile, methodical legal system, which “necessitates” the demolitions. At the same time, demolitions, and the coercive environment they create as a whole, cannot be divorced from Israel’s settlement enterprise. Both are part of a broader policy, and are performed under the pretense of legitimate authority.

Under Article 43 of the Hague Regulations, Israel, as the Occupying Power, must “restore, and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety” in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT). In carrying out this duty, a planning regime should serve the interests of the protected Palestinian population, but instead, the planning regime itself, as part of a larger dual set of laws and practices, obstructs the most basic rights of Palestinians.3 As 2016 has already seen shocking rates of demolition of structures and resulting displacement, it is important to again highlight the planning regime, and ask broader questions regarding the role of third states in maintaining the status quo.

Background

The 1995 Oslo II Accord divided the West Bank, excluding East Jerusalem, into three sections — Areas A, B and C. Area C covers approximately 60% of the West Bank, and is rich in natural resources, including fertile land, water, and minerals. Because Areas A and B are non-contiguous communities, any natural growth should spillover into Area C. Given its size and resources, Area C is integral for an independent Palestinian state,4 however, it is under full Israeli control.

Since 1967, some 250 settlements and outposts have been established by Israel in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.5 Approximately 300,000 Palestinians and 365,000 Israeli settlers currently reside in Area C,6 with an additional 200,000 settlers in East Jerusalem.7 What has brought us to this point of acute demographic “facts on the ground” is layer upon layer of military orders, laws, court decisions, and practices that create a comprehensive façade of legality and legitimacy. With everything entangled, an act that facilitates settlement growth becomes indistinguishable from an act that obstructs the rights of a Palestinian community.

Accordingly, before examining the planning and permit regime, two preceding “layers” of the system should be identified. First, the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) has failed to rule on the legality of settlements. In Bargil v. Government of Israel, the court examined whether the settlement of Israeli civilians in occupied territory was illegal. While the court said it would rule on specific issues of land disputes in the Occupied Territory, it asserted that it could not rule on the petition under review, holding that it was a political issue and non-justiciable.8 Although Israel uses settlements politically in order to establish “facts on the ground,” the issue of transfer of civilians is clear-cut in international humanitarian law.9 The Bargil judgment, along with countless others, highlights the court’s readiness to defer to the Israeli government in general and to authorities, notably the Civil Administration, involved in the expansion of Israel’s settlement enterprise, in particular.

Another layer in the process is the system that supports land confiscation in the West Bank. Methods used for confiscating Palestinian land by the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) include: requisition for military purposes, public needs (such as roads or nature reserves), and declarations of absentee land and state land. Each of these methods has some basis in the legal systems that were in force prior to the Israeli occupation —including Ottoman, British and Jordanian laws—and were then further amended by Israeli military orders.10

Following the 1979 Elon Moreh case, Israeli settlements could only “legally” be built on state land and not private Palestinian property. However, as with the broader system for land appropriation, the internal system of state land declarations was built to favor the state and may be disregarded entirely through retroactive legalizations of outposts. According to the Israeli Military Advocate General, the need to use state land declarations “stems from the fact that most lands in Judea & Samaria are not registered.”11 However, immediately following its occupation, Israel ended the process of registering land in 1968.12 While Palestinians have the right to appeal state land declarations, the process itself is deficient in fairness and independence.13 The 2012 Conclusions and Recommendations by the Commission to Examine the Status of Building in Judea and Samaria (the Levy Report) recommended “that the Appeals committee be composed of non-uniformed jurists, a factor which would contribute to the general perception of the Appeals Committee as an independent body, acting according to its own discretion.”14

Settlement Expansion and the Planning Regime in Area C

The Jordanian City, Village, and Building Planning Law (No. 79 of 1966) was in force in the West Bank prior to Israel’s occupation. The Jordanian planning law included a High Planning Council, as well as District and Local Planning Committees, and allowed for local Palestinian representation at each of these levels.15 In 1971, Israel significantly amended the planning law via Military Order 418, which annulled the District and Local Planning Committees (and with them, Palestinian representation at the planning level), and centralized decision-making under a High Planning Council whose members were appointed by the Israeli Military Commander.16

In total, the Civil Administration, a body within the Israeli Ministry of Defense, is responsible for implementing Israeli government policy in the West Bank, and has authority over zoning, construction, and infrastructure matters in Area C.17 Within this structure, the Central Planning Bureau is responsible for the High Planning Council, and for all planning in Area C, including Palestinian communities and Israeli settlements.18 While the High Planning Council has delegated some of its responsibilities to sub-committees, it must approve all plans in Area C.19 This inevitably creates a situation where one body is examining matters for two conflicting interests: one that is in line with government policy, and the other that is in line with international law.

In April 2015, the Israeli High Court reviewed a petition, which argued that Palestinians had no voice in the planning process and called for the restoration of district and local planning committees in Area C. While the court acknowledged that “the wishes of the population ought to be given expression today as well,”20 it reaffirmed previous judgments regarding the validity of Order 418. The court held “that wider questions of policy, land boundaries and so on…ought to be concentrated in the hands of the Civil Administration and the military commander, due to the importance of the plan that applies to land in a territory subject to belligerent occupation.”21

Indeed, the “importance of the plan” and how it impacts Area C is stark. Only 1% of Area C is planned for Palestinian development, construction is heavily restricted in 29%, and the remaining 70% is completely “offlimits for Palestinian use and development.”22 Palestinians in Area C must submit building permit requests for all structures, but due to the limited area (1%) planned for development, a negligible amount of permit applications are granted. Between 2010-2015, only 1.5% of permit applications were approved.23 Given the lack of a planning scheme in most Palestinian areas and the high rate of permit denials, Palestinians are essentially forced to build illegally and thus are exposed to demolitions.

There is a clear contrast between the treatment of Palestinian communities in Area C and that of Israeli settlements. While Palestinians were largely cut out of the planning process in the OPT via Order 418, and in violation of international law,24 Israeli settlers were brought into “the legal framework.” In order to accommodate the settler population and “apply various special norms to the residents,”25 the Israeli Civil Administration’s policy in Area C allows for settler participation in planning, zoning, and enforcement activities within settlement areas.26 Accordingly, settlers, whose opinion may not be binding but is nonetheless “a yardstick by which an ultimate decision will be measured,”27 wield sizable influence in the OPT, where 70% of Area C falls “within the boundaries of the regional councils of Israeli settlements.”28

The ability of settlers to participate in the planning process in Area C should be not only be compared to Palestinian involvement, but more importantly, be examined at the baseline of settlement illegality under international law. Therefore, while Israel feigns distinguishing between “legal” settlements and “illegal” outposts, they are one and the same in terms of their aim to colonize Palestinian land and their unlawful status under international law.29 The distinction between outposts and settlements only becomes important when comparing how Israel exercises its enforcement powers across Area C.

Illegal Structures in Area C

While planning and building activities may be carried out which are consistent with Israeli law (but remain in contravention to international law), it is important to note that settlers and regional councils also drive Israeli policy in violation of its own procedures. As noted in the Summary of the Opinion Concerning Unauthorized Outposts— Talia Sasson, Adv. (Sasson Report), commissioned by then-Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, “The ‘engine’ behind a decision to establish outposts are probably regional councils in Judea, Samaria and Gaza, settlers and activists, imbued with ideology and motivation to increase Israeli settlement in the…territories.”30 Alongside efforts by settlers and regional councils, the Sasson Report underscored the role of various state authorities in the establishment of outposts “in harsh violation of the law.” Over ten years after the report’s publication, outposts continue to be established and legalized. Israeli authorities undertook actions to formalize 25 outposts in 2014 alone, and continued such practices throughout 2015.31 In July 2015 acommittee was established in order to plan the retroactive legalization of outposts.32 While commenting on the committee, Israeli Minister of Justice Ayelet Shaked reaffirmed that most of the outposts were “set up by various Israeli governments.”33

Another case revealing the position of Israeli officials in regard to illegal settlement activity also occurred in July 2015. Following the demolition of two illegally built Israeli structures on private Palestinian land in the settlement of Beit El, Netanyahu quickly announced the approval of hundreds of new units in the same settlement.34 Three Israeli government ministers released a statement supporting the “residents of Beit El, their desire to build up their community, and their protest against the unnecessary demolition.”35 Netanyahu’s announcement of new construction in order to appease settlers was not unusual; illegal structures built by settlers are frequently demolished only after arrangements are made with Israeli authorities that may include relocation or compensation.36

These statements and actions by Israeli officials are in stark contrast to the treatment of “illegal” Palestinian structures and communities in Area C. There, the planning regime itself facilitates the destruction and confiscation of Palestinian property.37 Palestinians, including those with court decisions regarding title to their land, face an added difficulty in having positive judgments enforced.38 Since 1998, approximately 77% of demolition orders were for structures located on land recognized by the ICA as privately owned by Palestinians, with the remainder of orders on state land.39 Moreover, in comparison to the retroactive legalization of outposts, long-established Palestinian Bedouin communities in Area C are under constant threat of transfer due to Israel’s E1 plan.

Moving Forward

It is more than evident from the conditions on the ground that there is a system in place that promotes growth and stability for one community and conditions ripe for transfer for another.40 In assuming that Israel’s dual system will not change on its own, human rights organizations continually call for the international community to uphold their obligations in regard to the situation in the OPT.

The planning regime, which facilitates both settlement expansion and the destruction and confiscation of Palestinian property, is fundamentally illegal and violates peremptory norms of international law, including the right to self-determination, and perpetuates grave breaches of international humanitarian law.41 Accordingly, states must not recognize or engage with such a regime. More specifically, as State Parties to the Geneva Conventions, states must respect and ensure respect for the Convention. This includes prohibitions against the transfer of civilians and the destruction of property, among others, implicated by Israeli settlements.42 Further, state responsibility arises in the commission of internationally wrongful acts, including serious breaches of peremptory norms of international law.43 Israel’s settlement enterprise obstructs the Palestinian right to self-determination and, accordingly, imposes an obligation on third states to act. Israel’s own stance towards settlements does not preclude responsibility.44

While third states may continue to lack the political will to take bold action against Israel, through sanctions or other means, states may also look internally to ensure that they are not rendering aid or assistance.45 For example, a recent investigation found that between 2009 and 2013 alone, over $220 million was channeled from tax-exempt nonprofit organizations based in the United States to Israeli settlements.46 The money was used for activities ranging from the purchase of buildings in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, to the addition of facilities to attract residents.47

Longstanding American policy considers settlements illegitimate. Moreover, the granting of tax-exempt status in the United States requires that organizations are organized and operated for certain purposes,48 which are generally for the public good and in line with public policy.49 The policy of allowing hundreds of millions of dollars coming from the U.S., which help to sustain settlements and the discriminatory, unlawful settlement enterprise more broadly, is inconsistent with U.S. domestic law and foreign policy.

In upholding their international responsibilities, states must go beyond condemnation and an expectation that Israel will change its policy. States must begin to genuinely address Israel’s settlement enterprise — and not give effect to such acts — including by looking internally and acting in a matter that is consistent with domestic policy.

Endnotes

1Demolition spree carries on across West Bank; 435 people, including 234 minors, have lost their homes since January 2016, Btselem, 8 March 2016, available at http://www.btselem.org/ planning_and_building/20160208_demolitions_in_jordan_valley

2United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) occupied Palestinian territory statement, 2 March 2015, available at https://www.facebook.com/ochaopt/ posts/999946090051987?notif_t=notify_me_page

3Amongst others, this includes the right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions. See Article 11 of the Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. The presence of settlements more broadly impedes the Palestinian right to self-determination.

4Area C and the Future of the Palestinian Economy, World Bank, 2 October 2013, available at http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/10/18836847/west-bank-gaza-area-c-futurepalestinian- economy

5The Humanitarian Impact of Israeli Settlement Policies, OCHA, January 2012, available at http:// www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_settlements_FactSheet_January_2012_english.pdf

6Under Threat: Demolition Orders in Area C of the West Bank, OCHA, September 2015, p.3, available at https://www.ochaopt.org/demolitionos/demolition_orders_in_area_c_of_the_west_bank_en.pdf

7East Jerusalem: Key Humanitarian Concerns, Update August 2014, OCHA, available at https://www. ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_jerusalem_factsheet_august2014_english.pdf

8The Court held that it was predominantly non-justiciable because it intervened “in questions of policy that are in the jurisdiction of another branch of Government, the absence of a concrete dispute and the predominantly political nature of the issue.” Bargil v. Government of Israel, HCJ 4481/91, paras. 3-4(a), available at http://www.alhaq.org/attachments/article/238/91044810.z01.pdf

9Transfer is prohibited under Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. The Commentary of 1958 notes that Article 49 is “intended to prevent a practice adopted during the Second World War by certain Powers, which transferred portions of their own population to occupied territory for political and racial reasons or in order, as they claimed, to colonize those territories.” Available at https://www.icrc.org/applic/ihl/ihl.nsf/Comment. xsp?action=openDocument&documentId=523BA38706C71588C12563CD0042C407

10Land, Law, and Legitimacy in Israel and the Occupied Territories, George Bisharat, 43 Am. U.L. Rev. 467 (1994)

11Declaration of Land in Judea & Samaria as Government Owned Land, Israeli Defense Force Military Advocate General Corps (IDF MAG Corps), available at http://www.law.idf.il/602- 7243-en/Patzar.aspx

12Prior to the Ottoman period, established practice led to “only dwelling and limited appurtenant areas…as vested in absolute private ownership.” While advances were made in the registration process during the Ottoman, British, and Jordanian periods, a great deal of land was left unregistered due to custom. For example, by 1948, the British had only registered one-quarter of the land under Israeli control. Land, Law, and Legitimacy in Israel and the Occupied Territories, George Bisharat, 43 Am. U.L. Rev. 467 (1994), p.492

13Although individuals have up to 45 days to submit an objection from the date of the declaration of “state land,” the system of notice of the confiscation is often inadequate. The Military Appeals Committee, which hears objections concerning such declarations, is also a Civil Administration body. Costs for appealing are often prohibitive, as the burden is on the Palestinian owner. The UN has stated “the process to declare State land is not in accordance with the standards of due process and undermines the right to an effective remedy.” See Report of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories, 9 October 2013, A/68/513, para. 20.

14The Commission to Examine the Status of Building in Judea and Samaria, Conclusions and Recommendations, 2012, available at http://www.pmo.gov.il/English/MediaCenter/Spokesman/ Documents/edmundENG100712.pdf

15Planning to Fail, The Planning Regime in Area C of the West Bank: An International Law Perspective, Diakonia, September 2013, p.14

16Id.

17Civil Administration in Judea and Samaria, Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), available at http://www.cogat.idf.il/1279-en/Cogat.aspx

18Planning, COGAT website, available at http://www.cogat.idf.il/1337-en/Cogat.aspx

19Review- Zoning in Judea & Samaria, IDF MAG Corps, available at http://www.law.idf.il/602- 6944-en/Patzar.aspx

20Deirat-Rafaiya Village Council v. Minister of Defense, High Court of Justice, 12 April 2015, HCJ 5667/11, para. 23

21Id. at para. 23

22Area C of the West Bank: Key Humanitarian Concerns, Update August 2014, OCHA, available at https://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_area_c_factsheet_august_2014_english.pdf

23Under Threat: Demolition Orders in Area C of the West Bank, OCHA, September 2015, p.3, available at https://www.ochaopt.org/demolitionos/demolition_orders_in_area_c_of_the_west_bank_en.pdf

24Under Article 43 of the Hague Regulations, which is reflective of customary international law, the Occupying Power must “restore, and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety, while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country.” This includes both criminal and civil laws in force. As the Occupying Power, Israel may not deviate from the laws in force to benefit itself; rather, it has an obligation to administer the OPT in the interests of the Occupied Population. See “PHROC Raises Serious Concerns Regarding the Development of Master Plans Requiring Israeli Approval in Area C of the West Bank”, 31 December 2014, p. 3-4, available at http://www.alhaq.org/advocacy/targets/european-union/884-phroc-raises-serious-concernsregarding- the-development-of-master-plans-requiring-israeli-approval-in-area-c-of-the-west-bank.

25Zoning and Construction Law, Review-Zoning in Judea & Samaria, IDF MAG Corps, available at http://www.law.idf.il/602-6944-en/Patzar.aspx

26Restricting Space: The Planning Regime Applied by Israel in Area C of the West Bank, UNOCHA, December 2009, available at https://www.ochaopt.org/documents/special_focus_area_c_ demolitions_december_2009.pdf

27The Regional and Local Councils of Judea & Samaria, IDF MAG Corps, 22 June 2014, available at http://www.law.idf.il/163-6731-en/Patzar.aspx

28Area C of the West Bank: Key Humanitarian Concerns, Update August 2014, OCHA, available at https://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_area_c_factsheet_august_2014_english.pdf

29In the

30Summary of the Report Concerning Unauthorized Outposts- Talia Sasson, Adv., 10 March 2005, available at http://www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/aboutisrael/state/law/pages/summary%20of%20 opinion%20concerning%20unauthorized%20outposts%20-%20talya%20sason%20adv.aspx

31Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and in the Occupied Syrian Golan, Report of the Secretary-General, 20 January 2016, A/HRC/31/43, para. 24, 9.

32New Israeli Panel Eyes Legalizing West Bank Outposts, Haaretz, 22 July 2015, available at http:// www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-1.667139

33Id.

34Netanyahu approves more West Bank construction after demolition ruling, The Guardian, 29 July 2015, available at http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/29/netanyahu-approves-west-banksettlement- construction-demolition

35Hundreds of Young Settlers Clash Violently With Police at Beit El, Haaretz, 28 July 2015, available at http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-1.668329

36Under Threat: Demolition Orders in Area C of the West Bank, OCHA, September 2015, p.12, available at https://www.ochaopt.org/demolitionos/demolition_orders_in_area_c_of_the_west_ bank_en.pdf

37In response to the increase in demolitions, a UN representative stated: “Most of the demolitions in the West Bank take place on the spurious legal grounds that Palestinians do not possess building permits,” said Mr. Piper, “but, in Area C, official Israeli figures indicate only 1.5 per cent of Palestinian permit applications are approved in any case. So what legal options are left for a lawabiding Palestinian?” Press Release: Humanitarian Coordinator calls on Israel to halt demolitions in the occupied West Bank immediately and to respect international law, 17 February 2016, available at https://www.ochaopt.org/documents/hc_statement_demolitions_feb16_final.pdf

38“Indeed, in the few cases of evictions of settlers and demolitions or residential settlement construction in recent years, Palestinian landowners have yet to regain full access to their plots. Palestinian claimants have seen few if any improvements in terms of access to land and the protection of their private property.” Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and in the Occupied Syrian Golan, Report of the Secretary-General, 20 January 2016, A/HRC/31/43, para. 32

39Under Threat: Demolition Orders in Area C of the West Bank, OCHA, September 2015, p. 3, available at https://www.ochaopt.org/demolitionos/demolition_orders_in_area_c_of_the_west_bank_en.pdf

40The UN Secretary-General has noted “the Israeli zoning and planning policy in the West Bank, which regulates the construction of housing and structures in Area C, is restrictive, discriminatory and incompatible with requirements under international law…The planning system favors Israeli settlement interests over the needs of the protected population and makes it practically impossible for Palestinians living in Area C…to obtain building permits.” Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and in the Occupied Syrian Golan, Report of the Secretary-General, 20 January 2016, A/HRC/31/43Id. para 45.

41See International Court of Justice, Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion, para. 55, “The Court would observe that the obligations violated by Israel include certain obligations ergaomnes… The obligations ergaomnes violated by Israel are the obligation to respect the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination, and certain of its obligations under international humanitarian law.”

42Article 49 prohibits the transfer of civilians. Article 53 prohibits the destruction of “real or personal property belonging individually or collectively to private persons, or to the State, or to other public authorities, or to social or cooperative organizations…except where such destruction is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.” The international community at-large, the UN and the International Court of Justice all affirm the illegality of Israeli settlements in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.

43See generally Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, 2001, UN International Law Commission, available at http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draft_articles/9_6_2001. pdf

44Id at Art. 32.“The responsible State may not rely on the provisions of its Internal law as justification for failure to comply with its obligations under this part.”

45Id. at Art.41(2). “No State shall recognize as lawful a situation created by a serious breach within the meaning of article 40, nor render aid or assistance in maintaining that situation.”

46Haaretz Investigation: U.S. Donors Gave Settlements More Than $220 Million in Tax-exempt Funds Over Five Years, Haaretz, 7 December 2015, available at http://www.haaretz.com/ settlementdollars/1.689683

47Id.

48Exemption Requirements- 501(c)(3) Organizations, Internal Revenue Service- United States government, available at https://www.irs.gov/Charities-&-Non-Profits/Charitable-Organizations/ Exemption-Requirements-Section-501(c)(3)-Organizations

49J. Activities that are Illegal or Contrary to Public Policy, IRS, available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/ irs-tege/eotopicj85.pdf