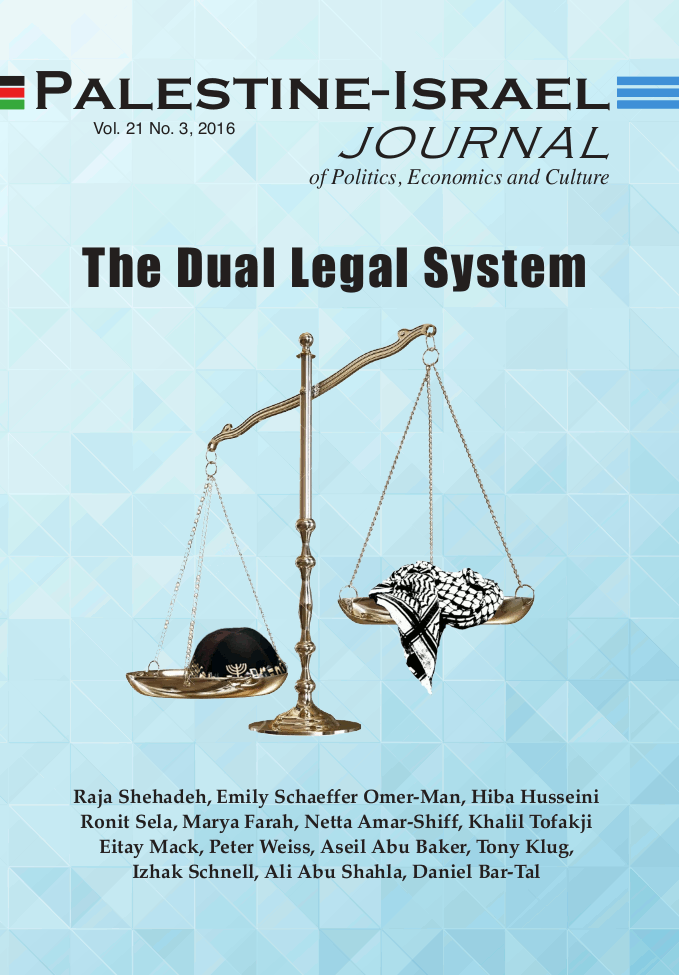

The concept of a ”dual legal system” has a long history, stemming from the beginning of Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank of the Jordan River in 1967. As I explained in detail in the early chapters of my 1985 book, Occupier’s Law, Israel’s ultimate aim is the annexation of the West Bank without its Palestinian inhabitants. However, the unlikelihood and difficulty of a mass expulsion of Arabs has meant that an interim period, pending full de jure annexation, has necessitated the creation of a particular legal relationship with the territory. Among the legal problems that arise in this interim period are the following:

- * How to apply Israeli law to the Jewish settlements in the West Bank while the area has not been annexed and is not under Israeli sovereignty. Related to this problem are the situations in which courts are to apply this law, which government departments are to execute it, and how to ensure that only the Jewish settlers will be subject to these laws, courts and government departments.

- * How to avoid applying the Israeli legal system to the Palestinian inhabitants.

- * How to reconcile this peculiar legal state of affairs with the requirements of international law.

Although the Camp David and Oslo Accords have affected elements of the legal situation in the West Bank over time, the underlying themes listed above have remained constant, as Israel utilizes the legal system in myriad ways in order to advance its agenda in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

The First System of Justice: The Local Courts

Under the full Israeli occupation that lasted until 1995, local Palestinian courts were kept weak, corrupt and ineffective. In order to understand why this was so, it is necessary to remember that local courts had been usurped of many of their powers; their jurisdiction was restricted to West Bank Palestinians and their internal affairs. The Jewish settlers were not subject to the jurisdiction of local courts, and activities of the military could not be reviewed there. Therefore, the adverse effects of a corrupted legal system were only suffered by the Palestinians. They did not hamper the activities of the military authorities, the establishment and development of the Jewish settlements, or life within the settlements.

The Assumption of Control by the Military

The single most influential officer in the military government of the West Bank as regards the local courts was the officer in charge of the judiciary. He was vested with all the powers and privilege of the minister of justice under Jordanian law,1 who had been granted powers by virtue of the law on the independence of the judiciary.2 Other powers this officer exercised included: the powers of the lawyers’ Bar Association,3 the Registrar of Companies,4 and the Register of Trademarks,5 Tradenames and Patents.6

When approached by lawyers and judges to improve the system and carry out improvements in the organisation of local courts, this officer’s response was that he was helpless to effect any changes. “Appointments nowadays,” he said, “are decided on political grounds.”

For a judicial system to function properly, the judiciary must be independent. Otherwise, it will serve the interests of those making the appointments, paying the salaries and deciding on promotions. The Israeli authorities undermined the independence of the West Bank judicial system, safeguarded under Jordanian law. A committee composed of military officers made the appointments, as well as decided on the transfers, promotions and salaries of judges and all other court employees.

The necessity for strict control over the courts became more essential due to the reduction of the stages of appeal from three to two by the 1967 abolition of the Court of Cassation, the highest court of appeals in the Jordanian system.

The Functioning of the Courts

In the early years of the Occupation, because of the general strike of lawyers and judges,7 confusion in the legal system could be justified. However, the fact that inefficiency and corruption continued to characterise the state of the local court system was inexcusable.

The Second System of Justice: The Military Courts and Tribunals

Unlike the situation of the administration of the first system of justice, the military authorities exhibited impressive efficiency in running the second system of justice, the military court system, which did not suffer from any of the problems plaguing the local court system.

There was rarely any delay in hearing cases which came before the military courts or other military tribunals. The witness and the accused were always summoned and the cooperation of the police was assured. Parties before the Objections Committee were always served with notice of the dates of the proceedings, and cases were heard and decided without hindrance or obstruction.

It is of no surprise that this should be so because the military had every interest in trying those accused of “security” offenses without delay. Cases involving objections against declarations of land declared as “state” land required a quick decision by the Objections Committee so as not to hinder the progress of the settlement in question.

The differences between the administration of the two systems of justice indicate that the military was able to administer efficiently when it was in its interest to do so. The military occupier who had assumed all the powers of the central government had done nothing to prevent the deterioration of the administration of the first system of justice.

The Military Courts

1. The Emergence of the Military Courts

Under international law, an occupying power is authorized to establish military courts to try cases of those charged with actions that endanger the security of the occupying power. On June 8, 1967, Israel established the military courts to deal with security offenses in the West Bank.8 With the passage of years, other tribunals were also established under the authority of the military. The matters over which military courts exercised jurisdiction increased, as those of the local courts were decreased.

Military courts were established in 1967 in five main cities in the West Bank: Hebron, Jenin, Jericho, Nablus, and Ramallah. They convened in the military headquarters of the respective military governors of these cities. Following the creation of the Palestinian Authority, the military courts were centralized in Salim, a village on the outskirts of Nablus, for residents from the north of the West Bank until the center, and the Ofer military camp, near the town of Betonia on the outskirts of Ramallah, for residents of the south of the West Bank until the center, while prisoners from Gaza are tried in Be’er Sheva.

The courts acquired concurrent jurisdiction over all criminal matters under the Jordanian Criminal Code.9 The decision whether a criminal case involving an offense under the Jordanian Criminal Code should be heard by a military court was reserved for the Area Commander. The military courts tried cases of murder committed by Palestinians against other Palestinians. The decision to transfer such cases to a military court often appeared to be due to the fact that the accused was a collaborator who the military was interested in protecting. The military court also heard cases involving traffic and drug offenses, and in the late 1980s offenses against the new military order No. 1121 involving price fixing.

In times of general unrest the court convened in a makeshift courtroom, sometimes close to a refugee camp, and held what came to be referred to as “quick trials”. In such trials, scores of offenders were tried together, usually without legal representation.

2. Detention and Legal Counsel

The Military Orders in force empowered the police to detain offenders without trial for a period of 18 days, after which the detention had to be renewed by a military court judge. In practice, the judge came to the prison, and the detainee was brought, without his lawyer, before him. The decision to renew the detention was usually based on the information supplied by the military prosecutor. Applications for release on bail were almost never accepted, and the court made it clear that it would not accept applications for habeas corpus.

Offenders before military courts had no absolute right of legal representation, but this was often misrepresented. It was falsely claimed10 that Military Order 29 (concerning prisons) does in fact grant an offender this right; however, the right to legal representation under this Order was subject to the discretion of the Prison Commander. When legal representation was allowed, the lawyer was not permitted to visit his client until the interrogation had been completed. Clearance to make such visits had to be obtained from the legal advisor to the military government. The delegates of the International Committee of the Red Cross (according to their agreement with the authorities) were entitled to see each detainee no later than 14 days after his arrest, but in practice, visits were only allowed at the end of this period if a confession had been made. Detainees were usually in complete isolation from the outside world during this period and, apart from the ICRC visit, remained so until an interrogation was completed or a confession was obtained. The agreement with the ICRC also contained a clause prohibiting the delegates from advising the detainee that he could see a lawyer or from passing on information to a lawyer should the detainee wish to instruct one.

Over the years, Military Order 378 (applicable to security offenses and the military courts) has been amended numerous times. In the few cases where the defenses made by lawyers on legal points have been successful, the Order has been changed to prevent future successes.

3. Judgments and the Right of Appeal

In a large percentage of the cases that come before the military courts, the judgment is based on a confession from the accused. The confession is almost invariably written in Hebrew — a language few Palestinians can speak or read.

Other Military Tribunals

Although the establishment of the military courts to look into security offenses is in accordance with international law, the creation of other military tribunals to hear civil matters is not.

The Third System of Justice: The Israeli Civilian Courts in the West Bank

At the time of writing Occupier’s Law, there were approximately 100 Jewish settlements in the Occupied West Bank, excluding Jerusalem, and about 32,000 Jewish Israelis lived in these settlements. Today, the number of government-sanctioned settlements stands at 125 (in addition to 100 more “settlement outposts”) with 350,010 Jewish Israelis, excluding East Jerusalem.

Israeli propagandists occasionally defend their settlement policy by blandly saying that there is no reason why Israelis should not be able to live in the West Bank just as Arabs are able to live in Israel. The implication is that Israeli settlers have the same status as the Arab inhabitants of the West Bank and are subject to the same laws and to the jurisdiction of the same courts. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Israeli settlements in the West Bank are de facto extensions of Israel. Their inhabitants are not tried before the local courts in any criminal matters nor, with a few exceptions, in civil matters.

Criminal Courts

There are three types of courts that may try Israeli settlers in criminal matters.

Firstly, they may be tried by criminal courts in Israel. In December 1967 a law was passed by the Israeli Knesset11 providing that “a court in Israel shall be competent to try under Israeli law any person who is in Israel for an act or omission which occurred in any region and which would constitute an offense if it had occurred in the area of the jurisdiction of the courts in Israel.”

Secondly, the Israeli settlers may be tried before the military courts in the West Bank, which have jurisdiction over all offenses committed there.12

Thirdly, they may be tried for certain offenses before settlement courts which the Military Commander was empowered to establish in March 1981 by virtue of Military Order 78313. These courts were initially called municipal courts, but Military Order No. 1057 has changed their name to “Courts for Local Affairs.” The jurisdiction of these courts was specified in regulations made in the same month and includes:

- (a) Offenses committed contrary to any of the Regulations made by the military authorities for the administration of local councils, with the exception of the rules for the election of the councils.

- (b) Jurisdiction to try offenses against any regulation made by the Council, or any offense committed within the area of the Council against any law or Military Order mentioned in the appendix to the Regulations.

- (c) Any other matters which shall be determined in the Regulations or in any other Military Order.

When Military Order No. 783 was published, the military authorities justified the establishment of courts on the grounds that they are only municipal courts with limited jurisdiction. Later their jurisdiction was extended and the name was changed by Military Order 1057 on June 22, 1983. This process of giving one justification for an action when it is introduced and later when the action is no longer the subject of public discussion, making changes that render the initial justification inapplicable, was commonplace.

Settlement courts are competent to impose the punishments determined in Regulations and in laws or Military Orders mentioned in the Appendix to the Regulations. As these Regulations are not published, and the request for copies by the author have not been met with any response, it is not possible to say what the extent of this jurisdiction is, or what penalties these courts may impose. It is, however, clear from paragraph (c) above that their jurisdiction can be extended indefinitely, simply by issuing secret Regulations or Orders.

The Area Commander appoints the judges of these courts and the public prosecutor. Judges of the courts of the First Instance are appointed from among the Israeli magistrates. There is also a Settlement Appeal Court, whose judges are chosen from among the judges of the Israeli District Courts. The Appeal Court can sit wherever the Area Commander designates.

The procedure and rules of evidence of settlement courts are those of the Israeli courts, and the courts have the same powers as an Israeli magistrates’ court to subpoena witnesses and in other matters related to a criminal hearing. The court also has the same powers as the military courts when it looks into violations of the law and orders.

Fines imposed by settlement courts are to be paid to the Treasury of the local Council. If a fine is not paid, the court may sentence the offender to up to one month’s imprisonment.

In Kiryat Arba (an Israeli settlement near the Palestinian city of Hebron), the first settlement court has been established and the judge is a magistrate judge from Jerusalem. The appeals are heard by three judges from the Israeli District Court in Jerusalem.

There is no law or Military Order that states Israeli citizens may not be tried before the local criminal courts, but in practice, it never happens. They are tried either before a military court, a settlement court, or an Israeli regular court. In addition, a circular (No 49/1350), dated December 6, 1984 and signed by the Officer in Charge of the Judiciary, added to the difficulty of having West Bank courts hear cases against Israelis. Addressed to all prosecutors and courts in the West Bank, it states: “Reference is made to document No 3/63 dated January 11, 1979, in which the legal advisor has interpreted the law on the West Bank whereby it is not possible to execute judgments from West Bank courts made against holders of Israeli identity cards who are living inside Israel (to include Jerusalem and its suburbs). Therefore, and to avoid problems in this respect, West Bank courts should not register any criminal case (to include traffic cases) against holders of Israeli identity cards unless written authorization is obtained from me.”

Civil Courts

Civil claims by or against Israeli settlers could be tried before Israeli courts or settlement courts or, in rare cases, the local courts.

In contractual matters, the parties could agree in the contract which court shall be competent to hear disputes. If the parties choose Israeli courts, no permit was required from the court for the purpose of serving process on the party residing in the West Bank outside the jurisdiction of the Israeli courts.

A special execution department was established in the West Bank by virtue of military order No. 348 in order to execute decisions reached by Israeli courts concerning property in the West Bank.

In contractual disputes where the parties had not agreed upon the forum, settlement courts or local courts could have jurisdiction. There were some matters that might arise between Palestinian and Jewish inhabitants of the West Bank over the jurisdiction of local courts. For example, in cases of civil wrongs, i.e. torts, the local courts continue to have jurisdiction. However, in practice it was not possible to start legal proceedings against a Jewish settler whatever the subject of the case. Jewish settlements are surrounded by barbed wire and entry to them is through a guarded gate, so any Palestinian entering there, regardless of the purpose of his visit, will be viewed with suspicion. The settlers are armed and enjoy extensive powers under the defense of settlement orders. If the Palestinian should announce that his purpose for entering is to serve court papers, he will likely be denied entrance, face harassment, and possible detainment.

It should be noted that Israeli norms were introduced in the West Bank on a personal, not a territorial, basis. That is, they related to the Israeli population in the whole region and were not restricted to the Israeli settlements. This (as has already been described in full above) has been done in two ways:

- (i) by enacting Israeli legislation which extended territorial laws of the state to the Israeli population residing outside the borders of Israel;

- (ii) through Military Orders.14

The Rabbinical Court

Local Arab courts may not look into matters of personal status of Jews. These matters are defined by referring to the Law of Religious Councils, No. 2, of 1938 (which is applicable in the West Bank) which includes matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance and custody.

In 1938, under the British Mandate, nine non-Moslem communities were allowed to have their own courts to hear matters of personal status between members of these communities, but a Rabbinical Court was not among them.

The relevant Military Order15 empowers the head of the “Civilian Administration” to establish Rabbinical Courts and Rabbinical Appeal Courts.

Conclusion

As the above has shown, Israeli plans to eventually annex the West Bank and establish in the meanwhile conditions that would allow the separation between Palestinian residents of the territory and Israeli residents were already in place by the early 1980s. When the first negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians began in 1991 the hope and expectation was that new arrangements would be forged which would eventually lead to a fully independent Palestinian state next to Israel. Instead, these negotiations that resulted in the Oslo Accords only consolidated, rather than did away with the legal arrangements for de facto annexation. The separation between the Palestinians and Israeli residents of the West Bank was achieved through the division of the area into three sections: Areas A, B and C. As to the military orders described above relating to separate court systems and jurisdiction in both civil and criminal cases as well as the execution of judgments in the various courts these were all included in Annex IV, Protocol Concerning Legal Matters, of the September 28, 1995 Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, which was a main component of the Oslo Accords. In other words, neither the long-term aims of the Israeli occupation nor the legal structures that were introduced during the period of full occupation were changed by the Oslo Accords, which failed to usher in a new period of peace between Palestinians and Israelis.

Endnotes

1Military Order Number 412.

2Military Order Number 310.

3Military Order Number 528.

4Military Order Number 267, Later amended by Order Number 362.

5Military Order Number 379

6Military Order Number 555.

7See West Bank and the Rule of Law, op. cit., pp. 45-50 for a discussion on the reasons and effects of the lawyers’ strike.

8Military courts were established by Order Number 3, later replaced by Military Order Number 378, which also specified security charges.

9Military Order Number 30.

10For example, in The Rule of Law in the Areas Administered by Israel, op. cit., p. 30.

11Article 2(a) of the Emergency Regulations (Offences Committed in Israeli-Held Areas – Jurisdiction and Legal Assistance) (Extension of Validity) Law, 1967.

12Military Order Number 30.

13See Military Orders Numbers 783 (as amended by Military Order 1058) and 892.

14For an account of the legal sysyem of the Israeli settlements see article by Raja Shehadeh in The Review of the International Commission of Jurists, No. 27, December 1981.

15Military Order Number 981 dated 11 April 1982, sections 2 and 9.