Directors: Mor Loushy and Daniel Sivan

Producer: Hilla Medalia, Ina Fichman

Co- Producer: Daniel Sivan, Mor Loushy, Kristian Mosvold

Executive Producers: Guy Lavie, Koby Gal Raday, Danna Stern, Dagmar Mielke, Barbara Dobkin, Jean Tsien

Country: Israel, Canada

Language: English, Hebrew, Arabic

On the last day of the 2018 Jerusalem Film Festival I saw The Oslo Diaries, which tells the “story” of the negotiations between the Israeli and Palestinian delegations which led to the Oslo Accords and the Palestinian recognition of the State of Israel on one hand, and the Israeli recognition of the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people on the other. The hope was that the so-called “Oslo Process,” which started with secret meetings outside the Norwegian capital in January 1993, would bring an end to the Israeli occupation and the establishment of an independent Palestinian state. The Loushy/Sivan film presents a sophisticated montage of the “diaries” of the major participants in this process, read in voice-over (by actors, I assume), in combination with retrospective interviews, mainly with the Israelis who had been directly involved, including the last recorded interview with Shimon Peres. Some of these “diary entries” are no doubt reconstructions, with the aim of reflecting on the development of the process in “real time.”

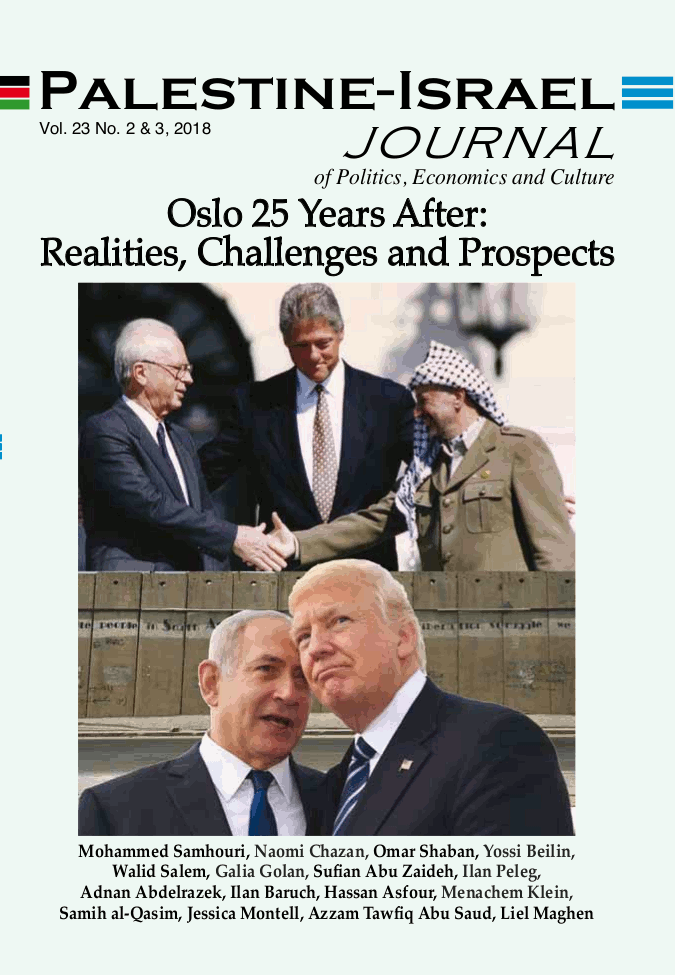

While the introspective texts (diaries and interviews) present the more hidden aspects of this process, the film also presents well-known footage from the signing of “Oslo I” on the White House Lawn on Sept. 13, 1993, with Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat shaking hands and signing the agreement which was supposed to lead to the resolution of the conflict between the two peoples; also footage of what became known as “Oslo II,” the agreement which led to the establishment of the Palestinian Authority, implementing the first step toward Palestinian self-government, is included. We are also shown how the forces of opposition led by Binyamin Netanyahu on the Israeli side and Hamas on the Palestinian side, generate violence: the massacre of 29 Muslim worshippers by a Jewish settler in Hebron in February 1994, the Palestinian suicide bombings, culminating at Dizengoff Center in March the same year. And finally, several Israeli rightwing demonstrations calling for the murder of Rabin, leading up to his assassination on November 4, 1995 and the impressive demonstration supporting the peace process — where he was assassinated. I must admit that when the well-known images from this demonstration where shown, my strongly personal identification from back then expressed itself in an attempt to see if my own presence on the square — which subsequently, after the assassination was named Rabin Square — had been “documented.”

The Oslo Diaries ends with Netanyahu’s close victory over Peres in the Israeli national election in May 1996, with a 50,000 vote margin. It is impossible to summarize the changes that took place during the previous three years and a few months. This period affected everybody, regardless from which perspective the events were experienced.

It was a strange experience to see this film in Jerusalem (in the so-called “heart” of the conflict), no doubt with a large majority of Israel spectators, most of whom probably had hoped that the Oslo Accords would put an end to the conflict, some of whom had even believed that it would be possible to share Jerusalem. The audience hardly moved in their seats, and except for a few uncomfortable laughs and somebody clapping after Rabin and Arafat had shaken hands on the White House Lawn, there was a tense silence.

The Oslo Diaries is an Israeli film, beginning with the Israeli pioneers of the Oslo Accords, Ron Pundak packing his suitcase to fly to Oslo with Yair Hirschfeld for the first meeting with the small Palestinian delegation led by Abu Ala (Ahmed Qurei), including Maher al-Kurd and Hassan Asfour. There is grainy footage from these meetings, and it is not difficult to see that there were moments of tension, but on the whole this is the beginning of what could be described as “a great friendship,” like in the movies. The intimate atmosphere, with quotes from the diaries taking us to the real-time experience and the tables set for the meals together, set the stage for the beginning of the process.

The only Israeli official who knew about this first meeting was Deputy Foreign Minister Yossi Beilin, serving under Shimon Peres. But gradually, with the talks progressing, the circle of participants widened. These included, on the Israeli side, Uri Savir, then a young director general of the Foreign Ministry, and Joel Singer, its legal advisor; and on the Palestinian side, some of Arafat’s closest advisors, like Nabil Sha’ath, the designated Palestinian foreign minister.

What The Oslo Diaries very convincingly shows is the importance of this intimate circle of negotiators, who were no doubt aware that they were able to provide the tools for changing the Middle East beyond recognition. This is the site where bonds of friendship are created. Singer jokingly tells about how he was kissed on both cheeks by Abu Ala. “Two kisses from a man I had never met before,” he says in a voice that signals the thrill of making peace with a former enemy. And Savir remarks that when he parted from Nabil Sha’ath after a round of talks in Taba, he had said, “Good-bye my friend,” to him.

What the film also shows — and this is much less encouraging — is that quite soon after the initial outbursts of joy in the streets on both sides directly after the handshake between Arafat and Rabin in Washington, the public arenas gradually became invaded by forces for whom the Oslo Process was nothing but a capitulation. We see how the distance between the two spheres — the intimate and the public — grows, how the inner circle begins to lose some of its common determination as the issues they have to deal with grow more complex and they need to provide solutions for implementing the agreements. This becomes most poignant after the Hebron massacre, when the suicide bombings resume and Rabin has to consider the possibility of removing the settlers from that city. Beilin, in one of the many interviews with him, says that Rabin promised him that he would do “something,” and adds that he turned on the radio every hour to hear the news of that decision, but it never came. Rabin had obviously — Beilin implies — missed the opportunity to clarify to the world what was acceptable and what was not.

The film does not answer the question of what made Rabin change his mind, or why he hesitated and kept postponing the decision. And would the outcome have been different if he had decided to evacuate the settlers from Hebron? These questions will never get a full answer. What the film shows though, is that the leaders on both sides had moments of doubt, when they were unable to bridge the personal warmth and certainty that was generated in the negotiating rooms and around the dinner tables on one hand, and on the other the streets or other public spaces where violence was generated, inside the two respective societies as well as between them. The images of the faces of Rabin as well as of Arafat, which for some reason look larger in The Oslo Diaries than they usually do on screen, show a slight tremor (or shiver) in their lower lips. This is something which they were apparently not able to control. Maybe neither of them had the self-confidence and/or sufficient trust in his respective partner to “give peace a chance.”

Whereas the dominant memory of the Oslo Process remains a sense of a lost opportunity for some, and a mistaken move for others, it also opened up numerous frameworks and institutions, more and less official, in which the culture of dialogue was fostered, and continues to develop new possibilities.