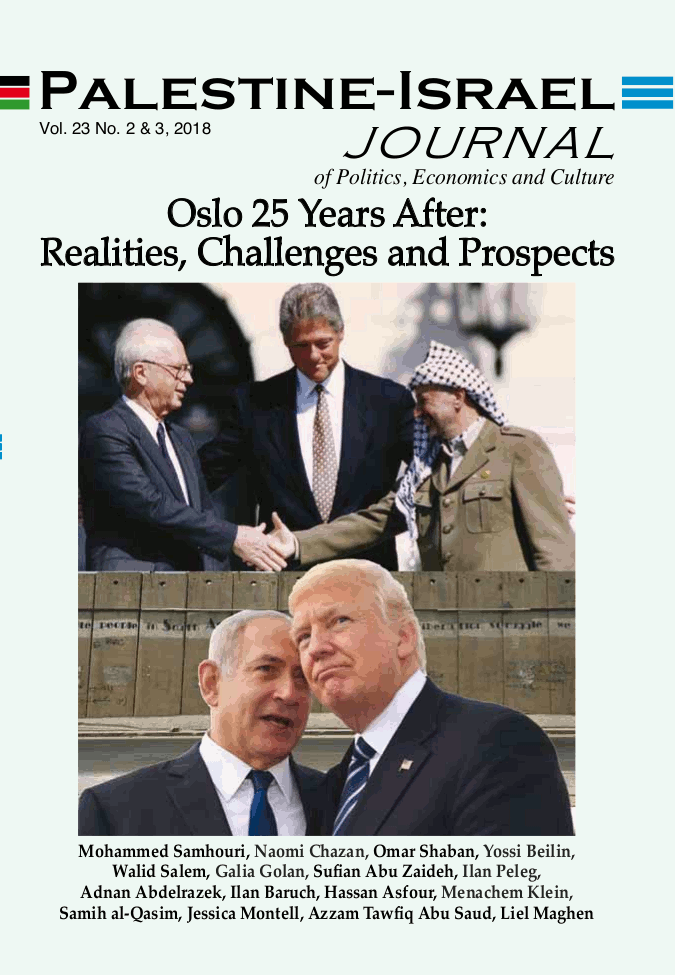

The Oslo Accords surprised America. Prof. Daniel Kurtzer, who at the time served as the assistant secretary of state for the region, was briefed about developments in the quasi-formal process but was generally kept at arm’s length. When Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres — who maneuvered Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s reluctant but ultimately resolved prime minister, into Oslo — got on a plane to brief Secretary of State Warren Christopher about the signing of initial understandings between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), he was unsure of the American response. In effect, Oslo transformed the Israeli-Palestinian landscape by establishing a framework that, to some extent still holds a quarter of a century later: restricted Palestinian autonomy over the Gaza Strip and the Palestinian cities and villages of the West Bank.

By the time of Rabin’s murder in November 1995, Oslo’s shortcomings were on full display. The Palestinians expected fewer settlements — and settlers — but got more; expected more freedom but got less; and expected better governance than the Israel Defense Forces’ “civil administration” but witnessed a feeble, at times corrupt, Palestinian self-rule emerge under tight Israeli control. Israelis wanted more security and more legitimacy from Palestinians but in reality experienced terrorism that, in their minds, exemplified festering Palestinian anti-Zionist sentiment. Worse still, there was no third party to monitor the faltering process.

If peace were to be forged, an outside party would need to step in. Thus, the United States took ownership of the peace process, and in the mid- 1990s it was optimally positioned to mediate between the sides. However, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s rise to power in 1996 cast a long shadow over the continuation of the interim process and the initiation of final status negotiations.

A Window of American Supremacy and Leverage

America’s supremacy was on full display: geopolitically after the end of the Cold War, militarily after its 1991 overwhelming defeat of the Iraqi military and diplomatically after the 1991 Madrid Peace Conference. Its president, Bill Clinton, despite some early political setbacks, was a popular president both at home and abroad, and the Israeli and Palestinian publics were no exception.

America had leverage with Israel and with the PLO. Its military and political assistance to Israel had been unmatched, and since 1993 it had dramatically increased its financial assistance to the West Bank and Gaza. America also had resources. It had the largest economy, the largest military and the largest geopolitical presence led by diplomats who cut their teeth managing the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of a new world order.

Finally, America had an interest in seeing the process through. It viewed stability in the Middle East as a key geopolitical interest. Normalizing relations between Israelis and Arabs figured prominently into U.S. regional strategy. And peace between Israelis and Palestinians was the centerpiece of Israeli-Arab normalization.

America remained a dominant regional force until the catastrophic consequences of its 2003 war in Iraq became evident during George W. Bush’s second term. Its regional stature took another hit when it became clear that America was no longer as interested in regional affairs when President Barack Obama came to power on an agenda set to end U.S. military adventures in the Middle East and strategically pivot from this hapless region toward the promising Asia-Pacific. Still, America’s close relations with Israel and Obama’s commitment to Israeli-Palestinian peace remained.

Three Failures of American Attempts at Mediation

Throughout the process that the U.S. came to own, it failed to do three things that would significantly enhance its probability for success. First, it failed to address Israel’s basic hostility toward Palestinian statehood. Second, it failed to help the Palestinians develop capacity that addresses the power disparity vis-à-vis Israel. Third, it failed to present and promote solutions to the core issues of the conflict.

1. Israeli Hostility to Palestinian Statehood

Since 1993, all Israeli prime ministers have been either ideologically opposed to, politically fearful of or militarily reluctant to endorse Palestinian statehood in earnest. Rabin’s last Knesset address outlined a vision of a demilitarized Palestinian autonomy in the West Bank. Peres, to his last day, preferred the Jordanian option. Ariel Sharon, who as a young general had fought Jordanian forces in the West Bank, saw its hilly terrain as a security asset never to be relinquished. Ehud Barak neglected the Palestinians to pursue his Syria/Lebanon agenda, and ultimately dealt with the Palestinians only as his political world came crashing down. Netanyahu has masterfully walked the status quo twilight between two states and one, fearful of both. Even Ehud Olmert, skeptical of Palestinian will and capacity, ran on a platform of unilateral Israeli withdrawal from most — but not all — of the West Bank until circumstances made him confront the Palestinian question head on.

Except for Rabin, who had led Israel before Palestinian statehood became an internationally accepted anchor of the peace process, all ultimately accepted the principle of Palestinian statehood. Most accepted it reluctantly; none pursued it relentlessly. By the time Barak and Olmert each found themselves in negotiations, their premierships were unraveling. Indeed, both cases reflected more political desperation and less a strategic move to address an existential threat to the Jewish state.

The U.S. never addressed this shortcoming in Israeli political will. No outside party can make Israel want something it does not. But a superpower that has serious leverage can deploy an array of coercive measures at its disposal. The U.S. could have forced Israel into enacting policies aligned with a two-state solution. At the very least, it could have prevented Israel from destroying the two-state solution. Clinton, Bush and Obama chose instead to merely encourage Israel to adjust its policies. For both ideological and political reasons, inflicting pain on Israel was never seriously considered. These are legitimate reasons. But they left the U.S. fighting an uphill battle with at least one hand tied behind its back.

2. Developing Palestinian Capacity

The second failure of U.S. policy was addressing the power disparity through the development of Palestinian capacity that could serve them in the negotiations. America indeed invested in what has come to be known as Palestinian “state-building.” The immediate tactical objective of this effort was the developing, refining and maintaining of Palestinian security capabilities with the primary task of addressing Israel’s security concerns. The U.S. understandably wanted to end violence in general, and specifically terrorism directed at civilians. The second intifada, with its horrific suicide bombings, essentially eliminated the Israeli peace camp and placed the Palestinian leadership on the wrong side of the Bush administration’s usagainst- them worldview. In its effort to help reform the Palestinian Authority (PA), the U.S. installed a three-star general as the U.S. security coordinator charged with the task of training Palestinian forces to primarily secure — and never resist — Israel and its occupation of the territories.

This focus on Israel’s security, absent any meaningful and visible rollback of the occupation, had two primary flaws. First, it undermined Palestinian public support for the PA, which was labeled an Israeli collaborator. Second, as Nathan Thrall demonstrates in The Only Language They Understand, violence has historically played a key part in pushing Israel into making compromises. And so the heightened — sometimes exclusive — attention to Israeli security ironically and counterproductively removed a prime motivation for meaningful engagement on the peace process.

There were more strategic objectives to capacity-building: first and foremost, creating and sustaining a Palestinian self-rule system — the Palestinian Authority — that would partly address Palestinian self-determination claims and mainly remove Israel’s existential threat of directly governing millions of Palestinians. Later, after Bush endorsed Palestinian statehood as official U.S. policy in 2002, and more so after Yasser Arafat’s death and the installment of Salam Fayyad as Palestinian prime minister, state-building efforts focused on effective, transparent and democratic governing, to the West’s liking. This government, it was hoped, would chase away memories of Arafat’s rule and could become a state if and when conditions would allow one to materialize. Notably, for those in the Bush administration who were ideologically aligned with Israel’s rightist leadership, state-building was a substitute for, rather than an accelerator toward, actual Palestinian statehood.

Whatever its flaws on the ground were, the capacity-building project never bridged the power disparity between Israel and the Palestinians that ultimately played a key role in undermining negotiations. The Palestinians never developed the needed agency that would catapult them into national self-determination: they never seriously tested strategic nonviolence, neither did they leverage the one-state agenda in the face of Israeli intransigence. More often than not, they defaulted into brazenly rejecting Israeli proposals without making public their counterproposals, fearing backlash from their own public in the face of concessions made, most notably on Jerusalem and refugees. To this day the Palestinians, ideologically and politically divided, look to outside powers for assistance. When the latter fail to deliver, the Palestinians implode into new levels of ineffectiveness.

3. Promoting Solutions to Core Issues

The third and final failure of America’s handling of the peace process was its reluctance to present a coherent and detailed set of parameters to resolve the core issues and to vigorously promote them with the parties.

Throughout the process, the U.S. opted for a hands-off approach when it came to identifying, formulating and advocating for solutions to the core issues: delineating borders between Israel and a new state of Palestine that can bridge the gap between the Palestinian demand for a state over all of the West Bank and Gaza Strip and the Israeli need to minimize the number of settlers that would need to be evacuated; determining the status of Jerusalem as the seat of two capitals, as well as identifying special arrangements needed for the handling of its holy and historical sites; resolving both the symbolic and intangible and the practical aspects of the Palestinian refugee issue; and devising security arrangements that can address Israel’s special security needs while respecting Palestinian sovereignty.

Rather, America’s self-described job was to get the sides into the negotiating room. There, it hoped, Israelis and Palestinians would somehow, some way reach agreement on the thorniest of issues. This was despite the unaddressed power disparity, despite years of maneuvering an interim process that bred mistrust rather than good faith and despite the political weakness of the negotiators on both sides.

The three American presidents under which the peace process unfolded hardly ever made public remarks on solutions to the core issues:

- • Clinton outlined an abbreviated version of his bridging proposal on all core issues in a speech to the Israel Policy Forum days before leaving office in January 2001.

- • Bush briefly (and vaguely) discussed borders in his 2002 address in which he called for a new Palestinian leadership and endorsed Palestinian statehood as U.S. policy. He then endorsed pro-Israel positions on borders and refugees in his 2004 exchange of letters with Sharon. Bush again addressed borders as he welcomed Mahmoud Abbas to the White House in 2005, and made a few more comments on the issue in his visit to Israel in 2008.

- • For his part, Obama delivered a landmark address on the Middle East in May 2011, in which he dedicated a total of one brief paragraph to borders and another to security. Netanyahu’s misrepresentation of Obama’s words forced the president to dedicate yet another clarifying paragraph in a speech to AIPAC a few days later. On security, Obama reiterated a few ideas in remarks he gave to the Saban Forum in 2013.

That’s it. In the quarter of a century since the core issues were outlined in the Oslo Accords, American presidents have dedicated a total of eight public occurrences to substantively discuss their resolutions. And they did so in a short and imprecise manner. This is a reflection of America’s hands-off approach guided by longstanding DC-truisms such as, “We can’t want it more than the sides” or “The only way forward is through bilateral negotiations.”

Real mediation, of course, is done mostly behind the scenes. But even there U.S. mediators faltered. Never — not once — in the history of the peace process, did the U.S. present the sides with a map delineating its border proposal. Astoundingly, this most rudimentary building block for a two-state solution was deemed too controversial for America.

Two chapters in the history of U.S. mediation merit special attention. The December 2000 Clinton Parameters are the main exception to the U.S. modus operandi of process managing, in so far as they were a coherent set of core issues ideas that were presented late — but still within — a negotiations process. The Clinton Parameters did not bring about a breakthrough toward an agreement, but they became arguably the most significant contribution toward a final status agreement, should one ever materialize. Almost two decades after their presentation, they are still the main reference against which actions on the ground and proposed solutions are measured.

Not less importantly, the Clinton Parameters became the basis for a variety of Track II initiatives that consolidated, clarified, and expanded the collective understanding on what a two-state solution would look like. On borders, Clinton envisioned a swap ratio favoring Israel, but land swaps would likely be equal. On Jerusalem, Clinton envisioned an open and undivided city, but sovereignty and security concerns will likely dictate a border regime that is amenable to a range of scenarios, including separation. More so on Jerusalem’s Old City, sovereignty in the al-Haram al-Sharif/ Temple Mount area will likely not be divided vertically as Clinton suggested, but rather a set of special arrangements — or a unified special regime — will moderate classic division of sovereignty.1

America attempted another, rather inconsequential, bridging proposal in the twilight of Secretary of State John Kerry’s initiative in March 2014. In the prior weeks and months, Kerry had discussed final status formulas with Netanyahu without a parallel Palestinian track. By the time Kerry and Obama presented Abbas with their proposal, the aging Palestinian leader was so disillusioned with Kerry and his initiative that he might not have accepted any offer. Certainly, he did not accept an underwhelming set of ideas, most of which were objectively inferior to what the Palestinians had heard, and rejected, in the past.

In December 2016, as the Obama Administration was transitioning out of office, Kerry gave a lengthy speech in which he outlined six principles for final status solutions based on his experience. The Obama administration considered enshrining such parameters in a United Nations Security Council resolution in the weeks it still had in office, improving U.S. positions and consolidating the international community’s understanding of a two-state solution. But the administration ultimately chose to let a largely symbolic, anti-violence, anti-settlements resolution pass instead.

Conclusion

Seventeen years, almost to the date, passed between the Clinton Parameters and Kerry’s six principles. One could only imagine what might have happened had the U.S. had vigorously promoted its final status proposals from early on and throughout the process.

A third party interested in bringing this conflict to an end, rather than engaging in an endless process, should impose consequences on spoilers, incentivize parties not just to maintain an elusive status quo (“do no harm”) but actually move toward a two-state reality, and identify solutions that exist within a realistic zone of agreement and actively promote them with the sides.

Even under such conditions, an agreement would not materialize without willing local leaderships. Only the sides themselves can ultimately sign an agreement. But left to their own devices they will likely not reach one.

A clear vision of the endgame is necessary for movement toward a two-state solution. The more it is anchored in international forums and resolutions — preferably a UN Security Council resolution — the better. This will not make an agreement between Netanyahu and Abbas any more probable. But such a resolution will significantly increase the likelihood of success of future negotiations under different Israeli, Palestinian and American leaderships.

Endnotes

1For more information, see the 2003 Geneva Initiative model final status agreement and its annexes, the work by the Aix Group on economic and other practical derivatives of an agreement, the Windsor-based Old City Initiative that dealt with Jerusalem’s Old City and its holy sites, borders works that took place under the Baker Institute and the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, refugee work done by MacGill University and Chatham House, just to name a few.