Israel’s occupation of the West Bank is temporary, at least in theory, so in line with international law the pre-1967 legal system remains in place. Thus, Jordanian law determines military cases — except where changed or supplemented by the 1,700 or so orders issued by the Israel Defense Forces since the start of the occupation.

In general, the penal code in the West Bank is harsher than in Israel: Murder carries the death penalty in the West Bank (although it has never been carried out), while in Israel the maximum sentence is life imprisonment. Attempted murder in Israel can draw 20 years’ imprisonment, but a life sentence in the West Bank. In the West Bank, Palestinians can be detained before seeing a judge for longer than in Israel, and there are fewer restrictions on detaining minors. The Jordanian penal code also differs from Israel; for example, rape within marriage is a crime in Israel but not under Jordanian law, and therefore not in the West Bank.

Israeli law does not apply to the West Bank, so Israeli settlers, in theory, should also be subject to military law. In practice, they are usually judged within the Israeli legal system. Settlers pay Israeli taxes and are governed by the Israeli institutions for education, religion, health and social welfare, while the land law is a confusing mix of Ottoman, British, Jordanian, military and Israeli law.

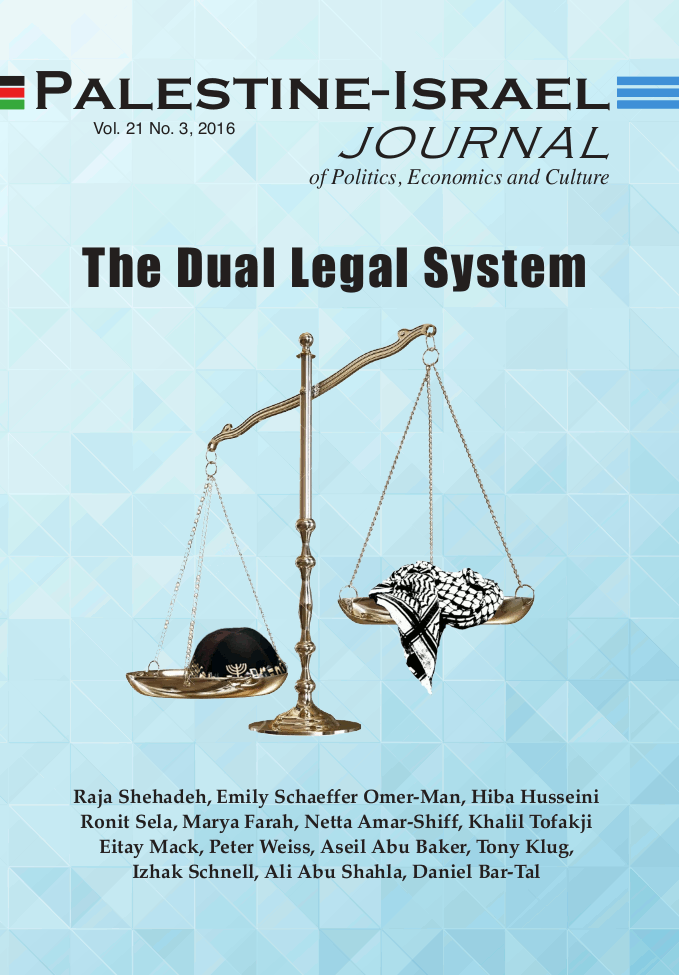

Thus these two systems of justice, and administration, run parallel, creating what the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination terms "de facto segregation." While that is an accurate description, it oversimplifies the issue. Israel does not refuse to apply its laws to Palestinians as an act of discrimination, but because it cannot and dares not do so without formally annexing the West Bank. This is an act which it has avoided, while a form of annexation is actually taking place via the spread of settlements.

Settlements and Israeli Law

Palestinians who work legally in Israel, inside the Green Line — currently numbering an estimated 84,000 — enjoy the same labor laws as Israelis (at least another 33,000 are estimated to be working illegally). An exceptional case arose in mid-2013: an Israeli court in Jerusalem ruled that Palestinians working in industrial zones in West Bank settlements were entitled to the salaries and benefits provided in Israeli law. “Public interest,” said the judge, meant that ten Palestinians in a stone plant were entitled to the tens of thousands of shekels’ difference between the salary they were paid and the minimum wage in Israel, as well as benefits such as holiday pay and pensions offered to workers within Israel.

This was taken further by a government decision to provide full protection to Palestinian workers (currently 26,000 Palestinians are affected) by January 1, 2014. The move outraged the Knesset Public Petitions Committee when members learned that since Israeli law does not generally apply in the West Bank, each law must be individually applied by an order from the army, and this could not be done by the set deadline. “It cannot be that Palestinian laborers work under slave-like conditions just because ministries can’t handle the schedule they gave themselves,” protested MK Adi Kol of the Yesh Atid party. However, the laudable aim of ensuring equality in benefits for Palestinians who work for Jews in the West Bank is a double-edged sword, as it means an extension of Israeli law into the territory and hence it advances a creeping annexation.

Israel must be careful regarding the extent of applying its laws to Jewish settlers. This became evident in May 2012 when a Likud member of the Knesset proposed a bill to extend Israeli law to settlements as a means of protection against Supreme Court orders for the demolition of houses illegally built on private Palestinian-owned land. Cabinet ministers who supported the bill rapidly reversed their votes after intervention by the prime minister, when the Knesset realized the extension of Israeli law to the settlements would mean a de facto annexation. The consequences of such an annexation had the potential to cause such serious international uproar that even right-wingers withdrew their support.

It is worth mentioning that the military courts, which deal with all criminal and security cases involving Palestinians, have a remarkable rate of convictions: 99.74% of cases in 2010. That would have been a proud record in the political trials of the former Soviet Union. The military appeals court also favored the prosecution, accepting 67% of appeals filed by prosecutors, in contrast to 33% by the defense. The courts heard 9,542 cases that year, of which 2,016 involved terrorism, 763 focused on disorderly conduct and the rest addressed Palestinians staying illegally in Israel, traffic offenses and criminal activity.

Legal Pluralism: From West to East, North to South

The dual legal system in the West Bank is not unique. “Legal pluralism,” a system in which different laws govern different groups within one country, exists in many parts of the world. In some countries, it is a relic of colonialism. For example, colonial law covered commercial issues, while others, such as family and marriage, fell under traditional law. Post-colonialism, the separation has tended to shrink, with people using whichever branch of the law they think will best suit them. In India and Tanzania, special Islamic courts deal with Muslim communities while secular courts address with other communities.

Modern Western legal systems can also be pluralistic, and legal pluralism may even be found in settings that initially appear legally homogenous. For example, there are dual ideologies of law within courthouses in the United States, where the formal ideology of written law exists alongside the informal ideology of law as it is used. Sources of Islamic law include the Koran, Sunnah and Ijima, while most Western countries take the basis of their legal system from the old Christian superpowers like Britain and France. Moral laws found in the Bible have been translated into everyday laws.

Legal pluralism also exists in societies where the legal systems of the indigenous people enjoy recognition. Thus, in Australia, elements of traditional Aboriginal criminal law are recognized, especially in sentencing. This has, in effect, set up two parallel sentencing systems. Legal pluralism is also alive and well in the Philippines, where the customary ways of indigenous peoples in the Cordilleras are recognized by the Philippine government. However, as a whole, pluralism is not universally welcomed. Some opponents are concerned that traditional legal systems and Muslim legal systems do not promote women’s rights. Members of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women call for unification of legal systems within countries.

Apartheid South Africa was a prime example of a dual legal system: one body of laws for everyone, and another set which dealt only with the majority black population, focusing on the traditional tribal system and covering aspects of urban life such as the provision of harsh penalties for anyone who challenged the government. A key aspect of apartheid's divide-and-rule policy was to push back against modernity in an attempt to strengthen tribal affiliations and controls from the past. The African National Congress (ANC) in fighting to end apartheid as retrogressive. In post-apartheid South Africa, the ANC is the ruling party, and ironically has strengthened the tribal chiefs’ system. Chiefs are given power in apportioning land in the rural tribal areas, and they hold their own tribal courts to administer justice specifically to tribal people. The ANC has also created a second house of parliament for “traditional leaders.”

As South African writer Thabiso Nyapisi has pointed out, accidents of birth and history, including the forced removals of the past, “can mean that people living on one side of a line on an old apartheid map are members of traditional communities with imposed tribal identities and limited constitutional rights. Those living meters away on the other side of that line enjoy the full benefits of post-apartheid South African citizenship.”

Manipulating the System: Israeli Appropriation of the West Bank

Returning to the West Bank, the existence of legal pluralism opens the way to using different methods to enable Israel to seize land. Since landlaw and history are often uncertain (people lack written title deeds), there is scope for ingenuity. First are “state lands,” which means using public lands previously under the control of the Ottoman Empire, British Mandate or Jordanian governments. The land is handed to settlers who hire private contractors to build houses and apartment blocks. The Israeli government, through its various departments, provides electricity, water, sewage, roads, ritual baths, schools and security through the army and private guards. Over time, that approach became more refined, with “state lands” referring to any uncultivated land. In order to identify possible “state lands,” Israeli officials used helicopters to survey the land in the West Bank. Once identified, land registries dating back to Ottoman times were checked for private ownership. The inherent flaw in this process is that Israel has no right to “state lands.” It has never annexed the West Bank and is only the occupying power, which does not give the government the right to use the land however it pleases.

The second method utilized by Israel is to issue a decree that land is needed for “military purposes” or “military needs,” though an army base may or may not then be built on it. The intent is to allow settlers onto the land, perhaps as crypto-soldiers, and in due course, the land becomes a settlement. Another way has been to secretly establish a “work camp” — this process was used to establish Ofra, which has now grown into a major settlement. Palestinian owners of confiscated lands are supposed to get some payment and even an annual leasing fee; however, even this shabby setup has been poorly administered with years-long delays.

Third, another trick is to claim that the pressure of satisfying “natural growth” requires creating “new neighborhoods” in existing settlements, which, in fact, are new settlements. The “natural growth” justification is dubious, considering the population of Israel increased at a rate of only 1.9% in 2012. In the same year, the settlements increased by 5%, 31.5% of which was directly attributable to immigration from Israel and abroad.

The fourth method is the outright confiscation of land belonging to Palestinians. Prime Minister Menachem Begin ordered a stop to this practice in the late 1970s and declared only “state lands” must be used, but it has continued. Private contractors erect buildings, and thus a settlement comes into being. The Peace Now movement revealed the staggering scale of it in a November 2006 report, which used official data of the Israeli Civil Administration, the government agency in charge of the settlements. It said that nearly 32 percent of the total land area of the settlements was privately owned by Palestinians: “the settlement enterprise has undermined not only the collective property rights of the Palestinians as a people, but also the private property rights of individual Palestinian landowners.”

Occasionally, the theft is exposed and is so blatant that the government is reluctantly forced to enforce the law. This was the case with the Migron outpost built on private Palestinian land in 2001 through government funding. After six years of repeated applications to court — and court eviction judgments repeatedly ignored amid government and settler ducking and diving — the government finally ordered the police to evacuate 50 settler families. Incentives were provided at taxpayer expense to buy off settler anger, including removal costs, temporary housing and $180,000 grants to each family. Even that was not the end of the story: Ten structures were left standing due to settler claims that they had bought the land. The attorney general ordered their destruction. Disputing continued.

The fifth method, utilized by young religious zealots, involves moving trailers onto a hilltop and creating an outpost, a move that could not occur without the knowledge of the army. Some of these outposts become permanent settlements, while the police and army destroy others with the youth furiously resisting evacuation.

Finally, the government simply does what it likes — which, for example, is what happened in November 2011 when the Netanyahu government was looking for ways to punish the Palestinian Authority for being accepted as a member of UNESCO. One of the sanctions was to announce a new wave of settlement construction: 2,000 housing units in East Jerusalem, and the expansion of two settlement areas on the West Bank. Legal pluralism makes it the Wild West Bank.