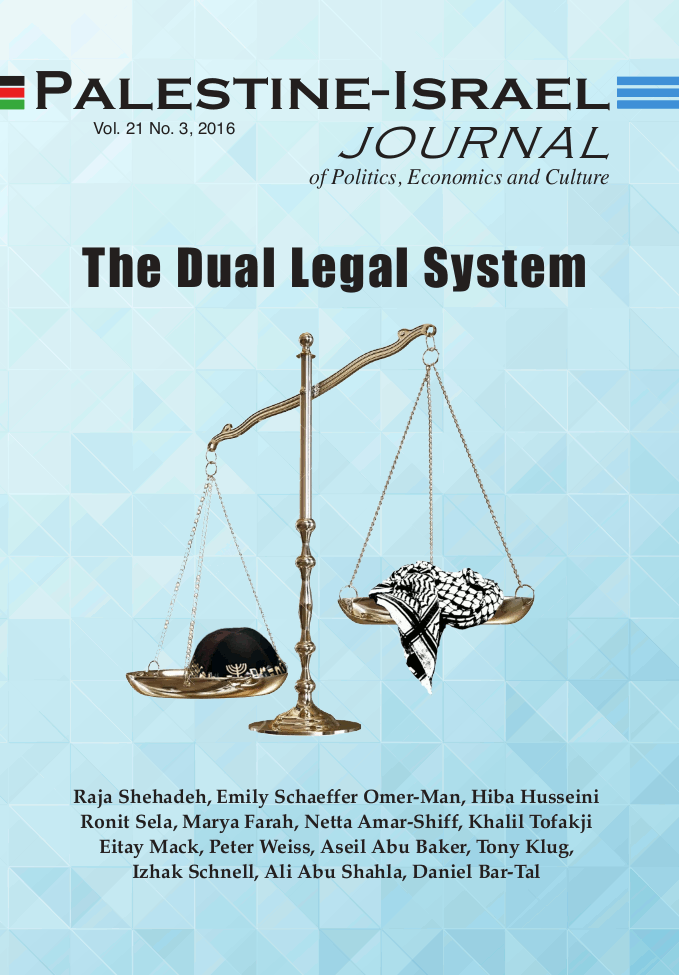

The evolvement of two separate legal regimes in the West Bank is one of the most prominent and troublesome characteristics of the Israeli occupation. This separation is premised on an ethno-national basis, reflected in every aspect of life, and severely infringes upon the rights of the Palestinian residents. The exceptional tapestry that comprises these two legal systems has been woven throughout five decades by various Israeli actors and methods: government policy decisions, parliamentary legislation in Knesset, military decrees and operations, legal opinions of the Ministry of Justice and the attorney-general and court orders handed down by military courts in the West Bank and by civic courts inside Israel, including the High Court of Justice.

Freedom of movement is one area — though certainly not the only one — in which the dual legal system has a decisive influence on the daily life of residents of the West Bank and on their basic human rights. Restriction of movement infringes not only upon the right to freedom of movement, but rather violates a range of rights. For Palestinians, those restrictions impact where a person can live, whether family members will be able to come and visit, how fast one can reach a hospital, which opportunities for studies and employment are available, and much more.

In the West Bank, freedom of movement is a function of nationality. The movement of Israelis is permitted in the vast majority of the region. The primary restriction imposed on Israeli citizens is that they are forbidden from entering the large Palestinian cities of Area A, which amounts to 18% of the West Bank. While settlers’ freedom of movement is not completely unencumbered, they do enjoy freedom of movement in all significant domains of their daily life, moving freely within and between the settlements as well as into Israel proper, and using the main thoroughfares available.

The situation of the Palestinians is completely different. For them, numerous restrictions limit their movement to, from and even within a given district of the West Bank. The many prohibitions imposed by the army throughout the West Bank are enforced through physical barriers, such as the Separation Wall, concrete roadblocks and inspection checkpoints. The rigid restrictions on travel between the West Bank and Gaza Strip and into Jerusalem have bred a dependency on the army for receiving limited and conditional entrance permits.

The wide-ranging and systematic restrictions imposed on Palestinians’ freedom of movement in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) perpetually violate their basic human rights. This occurs in spite of the fact that international humanitarian law — which constitutes the relevant legal framework for military occupations — places numerous obligations on Israel to protect the Palestinian population over whom it occupies. Moreover, international law clearly and unambiguously forbids the creation of settlements in the heart of the occupied land. The absurd result is that Palestinians, who are legally entitled to protection, do not receive it, while the settlers, who are legally forbidden from residing in the territory according to international law, benefit from protection and a litany of rights driven from Israeli law. As a consequence of the expansion of the settlement blocs, the human rights violations against the Palestinian people have increased and become more entrenched.

Three aspects of limitations on the freedom of movement of Palestinians will be briefly outlined in this article: physical restrictions on movement, limits on choosing one‘s place of residency, and traffic law enforcement that hinders on movement. In all three aspects, Israelis living in the West Bank or travelling through, as well as internationals visiting the area, enjoy a significantly greater level of freedom than Palestinians. The Israeli authorities routinely justify this discrimination against Palestinians by stating security considerations, both for national security and for the sake of providing protection to settlers.

Physical Restrictions on the Freedom of Movement

Movement in the West Bank is restricted by an array of physical barriers including walls, fences, iron gates, cement barriers and earth channels, as well as checkpoints through which ease of movement varies. Restrictions on the freedom of movement in general, and physical barriers in particular, increase markedly during episodes of tension and violence and shrink during periods of calm, but they never disappear entirely. During the Second Intifada, the restrictions expanded and became more extensive, yet as the Intifada subsided, portions were removed. The violence that began in October 2015 brought a partial return of the restrictions for days or for months on end. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, as of the end of 2015, there were a total of 543 checkpoints and movement barriers throughout the West Bank. These include, for example:

Roads for the use of Israelis: The policy of separating settlers and Palestinians has led to the construction of several highways between settlements and Israel proper, that are available to Israelis only as a result of the severe and encompassing restrictions that have been imposed on the Palestinians since the start of the second intifada. Most of these restrictions are not grounded in military decrees but are rather applied on the basis of oral orders and instructions given by soldiers and the Border Police. As of February 2014, Israel has allocated 65 kilometers of West Bank roads for the exclusive or almost exclusive use of Israelis. In different areas, such as Highway 443 leading to Jerusalem, Palestinians living in the area or travelling through it are forced to use adjacent and internal roads as alternatives to the highway.

Settlements and “Special Security Areas”: Different restrictions and prohibitions are placed on the entrance of Palestinians to the areas of the settlements themselves. Additionally, in 2002, the army established “special security areas” which encompass the external borders of some of the settlements and are intended to provide them with a protected space through fences, electronic sensors and cameras. Despite the fact that these areas are considered closed military zones and are meant to function as a “spatial deterrence” where entry is forbidden, in reality they are open and accessible to settlers. Palestinians who own private agricultural land within the confines of the “special security areas” are allowed to enter and cultivate their land only with prior coordination and permission from the Israeli army.

Exclusion from the barrier’s “Seam Zone”: In 2003, with the construction of the Separation Barrier, Israel began implementing a systematic separation regime in the area locked between the Separation Wall and the Green Line, which it named the “Seam Zone.” While Israelis and tourists have permission to reside in and travel throughout the Seam Zone at will, Palestinians have become dependent on a permits regime. This caused a wholesale isolation of entire Palestinian villages and a mortal blow to the ability of Palestinians to make a living from their agricultural land in all the areas west of the barrier.

The permits regime requires all Palestinians — even lifelong residents of the area — to receive from the army a special permit or certificate of residency in order to pass through, reside in, or cultivate their land. Palestinians are forced to cope with a long, complicated bureaucratic process to receive a “Seam Zone” permit granted by the military in a process that could last for months. Every permit is for a fixed period of time, requiring reissuing upon expiration. Each time, the applicant needs to prove his tie to the location under specific guidelines stipulated in a closed list of military orders, such as agriculture or commerce. Receiving an entry permit to the “Seam Zone” does not enable a Palestinian to traverse the area in total freedom; each Palestinian farmer has limited entry and exit from only one of approximately 80 gates. These crossings are not continuously open but rather confined to certain times, and most of them are only in operation for a few months of the year, primarily the olive harvesting season.

Restrictions on the Freedom to Choose One’s Place of Residency

Israel’s policies allow for Israeli citizens to choose to reside in a settlement in the same manner that it allows them to reside in any city or town throughout Israel. In this regard, no distinction is made between Israel proper and West Bank settlements. Conversely, Israel imposes a variety of restrictions on the freedom of Palestinians to change their place of residency in the West Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem. Due to such policies, the West Bank is partially closed off to Palestinians who wish to change their place of residency, yet by and large open to Israelis wishing to establish their homes there. Restrictions on the freedom to choose one’s place of residency will necessarily have a dramatic impact on many other aspects of one’s personal life path.

1967 ban on entering the territories: With the start of the occupation in 1967, the IDF published a military order declaring the territories a closed military zone and conditioning entry on receiving permission from the army. This decision was crucial to the approximately 270,000 Palestinians who had lived in the West Bank and Gaza Strip before 1967 but who were not present there when the military command conducted a census of the Palestinian population. Thus, all men between the ages of 16 and 60 were forbidden from returning to the territories. Over the years, the military command removed from the population registry the names of around 130,000 Palestinians who had been residing abroad for prolonged periods of time. Those who later sought to return and live in their homeland were prevented from doing so, while at the same time, any Israeli citizen wishing to move to a settlement could do so without any restrictions and without needing a permit.

2010 order preventing infiltration: In April 2010, Israeli authorities placed additional measures on the right of Palestinians to reside in the West Bank, this time through an amendment to the Military Order for the Prevention of Infiltration (Amendment No. 2) and an amendment to the Security Provisions (Amendment No. 112). Indeed, the language of the order enables its application to both Israelis and Palestinians, but upon its publication, the army spokesman clarified that it will not be used against Israeli citizens. The amendment to the infiltration order ruled that everyone in the West Bank without a permit from the military or state authorities would be classified as an infiltrator and subject to imprisonment even if their permanent place of residency was the West Bank. The result of this policy was the unwitting transformation of tens of thousands of Palestinians into criminals solely because they resided in the West Bank. They have no option to receive a permit to reside in the West Bank, and may be expelled from it even though they had lived there for many years or relocated there for the purposes of family unification.

Freezing “Family Unification” procedures: Beginning in 2000, with the start of the Second Intifada, Israel has frozen its handling of requests to grant a citizenship or residency status inside Israel to Palestinians from the Occupied Territories who are married to an Israeli citizen or resident. Israel has also refused to re-authorize requests that were approved in the past, and ceased to accept new requests for family reunification. The significance of this legislation has been that, for over a decade, thousands of Palestinians from the territories are no longer able to live normal family lives if their spouses are citizens of Israel or permanent residents living in East Jerusalem. Israelis who are born and raised in the West Bank, on the other hand, will encounter no problem when marrying someone who lives in Israel proper, and together will be able to decide whether to settle down in Israel or in the West Bank.

Preventing passage between the West Bank and Gaza: Throughout the years, Israel has hardened its policies regarding passage between the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Today, movement between the two areas is extremely curtailed and made possible only through specific permits. With the outbreak of the Second Intifada, Israel decided to cease updating addresses between the West Bank and Gaza as part of its overall policies to create a permanent separation between the two regions. Information that was registered at the time in the Israeli census was frozen and not subject to change, modification, or appeal. In 2007, Israel began to refer to Palestinians residing in the West Bank, whose registered address was in the Gaza Strip, as “illegal aliens” (shohim bilti khukim), even if they were in possession of a permit granted from the army. Accordingly, Israel began to forcibly transfer Palestinians from their homes in the West Bank to the Gaza Strip on the basis of the mistaken addresses that appeared in the population census. Moreover, in 2009, the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories published a registry that almost entirely blocked the possibility of individuals relocating from the Gaza Strip to the West Bank for residency purposes, with the exception of extreme humanitarian cases, and only after meeting excessively strict preconditions.

Movement Restrictions in the Framework of Traffic Laws

The principal purpose of traffic laws is to arrange the safe and orderly movement of vehicles and pedestrians. In the West Bank, certain aspects of traffic laws limit freedom of movement for Palestinians, yet allow Israelis freedom of movement. While Israel typically justifies the dual legal system in the West Bank as the necessary and unavoidable outcome of security considerations, traffic laws are clearly in the realm of civic law, and therefore undermine this claim. Israelis who violate traffic laws in the OPT are brought to trial in civilian courts in Israel in accordance with Israeli civil traffic laws. Palestinians, however, are tried in military courts and by military orders and rulings. Even though the essential traffic laws that apply to the two populations in the West Bank are similar, the manner in which they are implemented and enforced is far harsher toward the Palestinians.

Traffic tickets and fines: Traffic tickets given to Israelis and Palestinians for the same traffic offense that occurred on the same road are likely to be trivial for an Israeli driver, yet turn into an entire ordeal for a Palestinian driver. Thus, if Israeli police officers come across a Palestinian driver who has been late in paying a traffic ticket, military legislation permits them to confiscate his or her driving license and even vehicle documents. In the event that a ticket has been given to Palestinians who had not yet paid a previous traffic ticket, the police are authorized to invalidate their driver’s license and even impound their vehicle on the spot. Thus, a person’s ability to lead a normal life is suddenly hindered; he cannot drive to his place of work, take the children, go shopping, obtain medical care, etc. None of these obstacles or punishments is meted out on Israeli settlers or on Israeli citizens visiting the area, because Israeli traffic laws do not allow such measures to be taken as they constitute an unacceptable infringement on freedom of movement.

Standing trial in a military court: Approximately 3,000 Palestinians stand trial in a military court every year for traffic-related offenses. Military judges are often inclined to reprimand Palestinian drivers who have not come to court to settle all outstanding matters, yet Palestinians are systematically not given the relevant telephone numbers through which they can inquire where their court session will be held. Tickets issued to Israelis do contain that information. When a court ruling is delivered for a Palestinian who is absent from the court session, that individual is obligated to obtain the court ruling by himself, a process which entails a significant number of difficulties. This is in direct contrast with procedures for Israeli drivers, to whom court rulings and payment vouchers are sent directly via mail. An inspection by the Israeli State Comptroller concluded that court decisions concerning traffic violations committed by Palestinians are not transferred to the police’s computerized system, which renders it difficult to trace the court decision and fine payments. Failure by a Palestinian to pay the fine by the assigned date is likely to lead, among other things, to the cancellation of an entry permit to Israel for a period of up to several months. This in turn is likely to severely harm the ability of a person to make a living, having a detrimental impact on the welfare of an entire family.

In general, punishments for traffic violation in the military courts are far more severe than similar infractions where the legal process is carried out in a civil Israeli court. In a Knesset debate, a police officer heading the Transportation Department in the West Bank stated, “The local Arabs are tried in the military court, and the rulings that are delivered there are among the most severe, far more than those that are delivered within Israel.” This, as previously mentioned, takes place in a domain that is unequivocally civilian in nature.

Conclusion

The scope of the infringements of Palestinians’ freedom of movement, as well as the implications of these infringements on other rights, is far greater than the examples presented in this article. To mention but a few additional examples: the dire consequences of the draconian restrictions on the entry and exit of people and goods to and from the Gaza Strip; the many prohibitions of movement in the Israeli-controlled parts of Hebron, which created a ghost-town effect; the severe deterioration of East Jerusalem as a result of its separation from the West Bank; and the situation of Palestinians being pushed out of areas declared military firing zones or archeological sites.

These and other hardships are the result of the systematic separation that exists on the ground and within the legal framework of the dual legal system. The separation essentially exists between Palestinians on the one hand, and all those who are not Palestinian on the other hand, be it settlers, Israeli visitors or international visitors. The basic principles of international humanitarian law, meant to protect residents of the occupied territory, are routinely ignored, leaving Palestinians exposed and highly vulnerable.

The full ACRI report devoted to “One Rule, Two Legal Systems: Israel’s Regime of Laws in the West Bank” can be accessed at: www.acri.org.il/en/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Two-Systems-of-Law-English- FINAL.pdf