On the 14th of February, I attended a tour of the village of Nabi Samwil (also know as al-Nabi Samuil) conducted by an Israeli activist connected to a new NGO called Park in a Cage. This small Palestinian village of approximately 250 inhabitants is located just north of the post-1967 municipal borders of Jerusalem, on a strategic hill overlooking both Jerusalem and Ramallah. Upon arriving at the top of the hill the sight is somewhat surprising, with its juxtaposition of ancient ruins to the left and a ramshackle village to the right, delineated by a few hundred meters of graveled road and a prominent security tower. Though Nabi Samwil’s story illustrates some of the deeper problems associated with occupation, its historical and religious heritage have made it a particularly complex case.

A Site of Historical and Religious Significance

Nabi Samwil is traditionally believed to contain the tomb of the prophet Samuel, a figure respected by all three Abrahamic faiths. The Byzantine Christians were the first to identify it as the burial place of Samuel, and over the years it has become a place of pilgrimage for Christians, Jews and Muslims alike.

Nabi Samwil has also been identified as the place referred to as “Mount of Joy” during the Crusader era; it is said to be from there that the Crusaders first set eyes on Jerusalem. Due to its strategic location, they built a monastery and church on the lands, as well as a fortress to fend off raids on northern Jerusalem. Following the defeat of the Crusaders, the area came under Muslim control until the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the start of the British mandate era in 1919. Our guide informed us that for most of the last few hundred years, Jews and Muslims were able to access and worship at the site alongside each other.

From 1948 to Today

Following the 1948 war, Nabi Samwil became a Palestinian village under Jordanian control, and remained as such until the Six Day War of 1967, when it was annexed by Israel. A large portion of the population fled to Jordan at that time, among them one of our tour guides, Eid Barakat, a villager who spent the next 22 years living in Amman before returning to his home in Nabi Samwil with his wife when his father fell ill.

In March of 1971, the Israeli military demolished the houses that surrounded the village mosque without notifying residents or providing them with an explanation, and the families were relocated to abandoned houses a few hundred meters east of the site. Part of the mosque was turned into a Jewish religious site, and the area surrounding it was declared an archeological park, allowing excavations to be carried out amidst the remains of the village’s homes throughout the ‘90s.

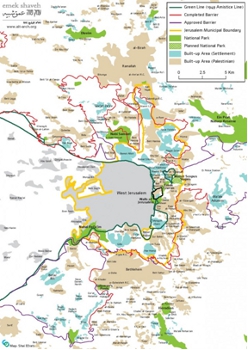

These digs uncovered several remains from a variety of different eras, among them remains from a large settlement from the Hellenistic period and of a fortress and trench from the Crusader period. In 1995, the village and the lands surrounding it were declared a large National Park, and this past June the Israeli Military’s Civil Administration (CA) submitted a plan to turn the area into a big tourist center. Today, the plans are being gradually realized, and one can now see in front of the various archeological remains tourist plaques recounting the history of the area with detailed blurbs and timelines.

Disinformation

One of the first problems associated with the conversion of this area into a tourist attraction is disinformation, which refers to the mixing of truth with false and/or missing facts that incite the observer/reader to draw false conclusions. It becomes apparent from the very first tourist plaque, which includes a timeline describing the history of the area and declaring that following the end of the British mandate in 1948, Nabi Samwil and its surroundings came directly under the control of the State of Israel, conveniently erasing the site’s history from 1948 to 1967. As we were listening to the description of the village’s history and religious significance, Eid pointed at one of the ruins higher up on the hill, close to the Mosque, and explained in Arabic that this particular house had belonged to his grandfather, and recalled some of the moments he had spent there as a child. Our guide then clarified that what was being presented on the plaques as an excavation site containing Hellenistic ruins, which for the most part it was, was not entirely true. Only parts of what we were seeing were the ruins of a Hellenistic settlement; the rest were the remains of the houses destroyed in 1971.

The Separation Barrier: Pressures and Implications

The problems for the villagers became magnified in 2007 with the creation of Israel’s Separation Barrier, which has cut the village off from the rest of the West Bank. Nabi Samwil is located in what is referred to as a Seam Zone, a land area in the West Bank located east of the Green Line (the demarcation line set out in the 1949 Armistice Agreement between Israel and its neighbors) and west of the Separation Barrier. These zones, which the Israeli military regards as ‘buffer zones,’ are closed to all Palestinians who do not have permanent residency in one of the villages located within the zone. Though the villages are situated on the Israeli side of the barrier, the villagers are unable to go into Israel, and therefore remain trapped between a territory they cannot enter (Israel) and areas that they can only access through a limited number of grueling checkpoints (West Bank). The lives of people within these areas are closely monitored, and their access to goods and services are restricted.1

Though the villagers in Nabi Samwil used to be able to work in Northern Jerusalem (the closest neighborhood is Ramot, just a kilometer down the hill) and access goods and services in the West-Bank, this has dramatically changed in recent years. Though there are no physical barriers preventing the villagers from entering Israel, anyone caught going too far down the hill without a permit is subjected to severe penalties. Eid told us that usually the first time a villager is caught, he/she faces two weeks imprisonment and about 500 shekels in fines, a sentence that doubles upon being caught a second time, and doubles again upon being caught a third time. Permits are hard to come by, and are usually only issued in cases of emergency. Eid explained that his wife was able to obtain a twenty-four hour permit to cross Jerusalem to go to a hospital (in East Jerusalem) when she fell ill, but that no permits were granted to her family members, forcing her to go alone.

Due to Nabi Samwil’s strategic location overlooking northern Jerusalem, Israeli military forces have installed a security tower in the middle of the village. With its security cameras, the tower allows the security forces to observe the comings and goings of the villagers, making sure that they do not go too far down the hill into Israeli territory.

Eid describes his life as being lived within the confines of an invisible cage: family members are unable to visit due to permit restrictions, villagers cannot work in the closest neighborhoods of northern Jerusalem, and if they are able to find work in the West Bank, they have to face the checkpoints day in and day out. The number of goods they bring back into their village is also severely restricted. One of the many examples Eid mentioned took place on Monday December 2nd, 2013, when families from Nabi Samwil and the nearby village of al-Khalaylah requested to bring in laying hens from the West Bank back to their respective villages through the al Jib checkpoint. These hens had been donated by the Norwegian People’s Aid fund, which gifted 45 laying hens per family, for a total of 405 hens. The Civil Administration denied the request, citing that because the villagers lived in the Seam Zone, they were only allowed to bring in quantities that would be used for domestic purposes and not for commercial use. Eid told us that they were eventually able to bring the hens in by illegally crossing into the seam zone through holes in the barrier.

Nabi Samwil as an Archeological Site and a National Park: Implications

Besides the problems created by the Separation Barrier, Nabi Samwil faces a further set of restrictions imposed by the categorization of the area as an archeological site and a national park. Due to this classification, the residents are unable to build on the land or improve their infrastructure; they cannot build extensions, plant trees, etc. This has several implications, first of all because it means that inhabitants cannot generate any business in the village. Even farming becomes difficult, as the villagers cannot plant trees, grow plants or set up animal pens to keep their animals. The French government donated a sheep pen, which was subsequently taken down by the CA. Furthermore, residents of Nabi Samwil who fled the village following the Six Day War and are currently living in Jordan, East Jerusalem or elsewhere cannot return to their ancestral home, as the village has been limited to the ten houses that were not destroyed in 1971. This also means that as families grow, the sons and daughters of villagers eventually have to move away from the village and into the West Bank thereby forfeiting their right to return.

Maybe the most powerful example is that of the school. The Nabi Samwil School used to be located on the upper floor of the mosque, but was moved after 1967 to a little building at the entrance of the village. The school is much smaller than it previously was, and is comprised of a single classroom with a class size of about six or seven students, which cannot accommodate the more than 50 children living in the village. Due to the restrictions the school cannot be expanded; instead, children have to commute everyday through the checkpoints to schools in nearby villages. The villagers have set up a small caravan just outside the school that can accommodate a few more students, but Eid explained that this is in fact illegal and that they expect it to be taken down sooner or later. He jokingly added that the trees the children planted in the old tires in front of the school are also illegal. Though he said this lightly, we were then told that extensions, trees and signposts are regularly taken down, including a ‘Welcome to Nabi Samwil’ sign the villagers put up at the entrance of their village. What’s more frustrating is that the plans to convert the area into a tourist center allows the CA to construct roads, parking, a restaurant and many other attractions to encourage tourist activity, yet the villagers will be unable to profit from tourism by opening their own local restaurant, shop or vegetable stand.

The extent and intensity of the pressures exerted on the villagers leads one to question whether the CA is intentionally trying to push out the current residents in order to realize their plan of transforming the area into a fully-fledged archeological tourist attraction. After all, Nabi Samwil is located in Area C (Palestinian land temporarily controlled by the Israeli military as stipulated by the Oslo Accords), land intended to eventually be retransferred to Palestinian jurisdiction. Chasing out the Palestinians and transforming the area into an Israeli-owned archaeological tourist attraction would give Israel cause to keep the area as a part of its territory despite previous arrangements under the Oslo Accords. Our tour guide summarized the situation quite well when he explained that the area should be open to all due to its historic and religious heritage, but the village adjacent to the archeological site should also be allowed and encouraged to thrive.

What Next?

Emek Shaveh, an Israeli organization of archeologists and community activists, has explained that “the area of the antiquities site is approximately 7.5 acres. Despite this, the Nature and Parks authority declared an area 100 times this size a national park, based on its unique flora and Mediterranean landscape. A visit to the national park clearly attests that there is almost no flora on these lands-certainly, no unique Mediterranean flora. As far as we understand, with the exception of the archaeological site, there is no justification for declaring the site a national park.”2 The organization concluded that “Nabi Samwil is a village in danger of forced dissolution and abandonment. The exodus of young people, lack of employment, the National Parks Law, and the difficulties that the authorities heap upon the villagers, leave no hope or possibility for development of the village”.

Since December 2013 the residents of Nabi Samwil have been carrying out demonstrations every Friday against turning the archaeological site into a tourist attraction. Emek Shaveh has provided the following recommendations necessary in maintaining both the area’s historical and religious heritage as well as ensuring the wellbeing of the villagers of Nabi Samwil. I must note that these recommendations are based on the understanding that the destruction of the village and the conversion of the site into an archeological tourist site are, unfortunately, fait accompli:

- “1. The residents must be allowed to build and expand their homes in the developed areas in their ownership. The construction of animal pens, the planting of fruit trees, and the creation of paths can take place in the many areas that have no antiquities or endangered flora.

- 2. Residents must be allowed to develop businesses in the village alongside the antiquities site.

- 3. Nabi Samwil is a place of Jewish prayer and tradition, as well as Muslim tradition. Both sides have stated that there is almost no religiously based friction, due to the respect for belief and religion. Strengthening the status quo by emphasizing the religious importance of the site can lower the tension between the sides and enable them to live in respect until a political agreement it made between Israel and the Palestinians regarding the site.

- 4. The area declared as a national park must be reassessed and reduced to the minimum extent.

- 5. The village of a-Nabi Samwil must be presented to visitors, both on the information sheet and on the site’s signage.

- 6. Tourist development of the place must involve the village residents and enable them to enjoy the economic opportunities presented by tourist traffic.

- 7. Development of infrastructure for the archaeological site must include development of the infrastructure for the village.

- 8. Development of the site and the manner in which is presented to the public must take place in coordination with village residents.”3

Eid Barakat holding a photo of Nabi Samwil prior to 1971.

1Map provided by Emek Shaveh. It is available from http://alt-arch.org/en/nabi-samuel-national-park/

2Quote and more detailed information available from: http://alt-arch.org/en/nabi-samuel-national-park/

3 Recommendations available from Emek Shaveh’s website: http://alt-arch.org/en/nabi-samuel-national-park/